The global communications network, a vast and intricate web, relies heavily on a colossal infrastructure often hidden beneath the waves: undersea cables. These fiber optic arteries transmit the bulk of international data, connecting continents and facilitating instantaneous communication across the globe. The concept of “tapping” these vital conduits, whether for intelligence gathering, industrial espionage, or even illicit activities, presents a complex and multifaceted challenge, both technically and ethically. This article aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the methodologies, historical context, and implications surrounding the interception of data from undersea cables.

The foundation of modern global communication is an extensive network of submarine communications cables. These cables are not merely thick wires; they are sophisticated bundles of optical fibers, protected by multiple layers of sheathing designed to withstand the harsh deep-sea environment. From their initial deployment in the mid-19th century as transatlantic telegraph cables to the current era of petabit-per-second fiber optic systems, their evolution reflects a continuous drive for greater bandwidth and reliability.

Cable Characteristics and Composition

Modern undersea cables are engineered for extreme durability and high performance.

- Optical Fibers: The core of the cable consists of hair-thin glass or plastic fibers that transmit data as pulses of light. Each fiber can carry numerous channels, significantly increasing data capacity.

- Buffer Coatings: Each fiber is surrounded by protective polymer coatings.

- Strength Members: High-strength steel wires or aramid yarns provide tensile strength, protecting the fibers during laying and against deep-sea currents.

- Copper Sheathing: A copper tube encases the optical fibers, providing electrical conductivity for powering signal repeaters and additional protection.

- Polyethylene Insulation: This insulating layer protects the copper conductor.

- Outer Jackets: One or more layers of robust plastic, such as polyethylene, offer abrasion resistance and overall protection against environmental factors and potential impact.

- Armoring (for shallow water): In shallower waters close to shore, cables are often reinforced with heavy steel wire armoring to protect against fishing trawlers, anchors, and natural abrasions.

Geographical Distribution and Landing Points

These cables span ocean floors, converging at critical landing stations on coastlines. These stations, often unassuming buildings, serve as the gateways where undersea traffic transitions to terrestrial networks. The routes frequently follow contours of the ocean floor, avoiding hazardous areas like volcanic vents or active seismic zones. The concentration of cables in certain choke points, such as the Suez Canal, the Strait of Malacca, or various shallow straits, makes these locations theoretically more vulnerable, yet also heavily monitored.

For those interested in the intricate world of undersea communications, a related article that delves deeper into the technical aspects and implications of tapping undersea cables can be found at this link: How to Tap Undersea Cables. This resource provides valuable insights into the methods used, the challenges faced, and the potential consequences of such actions on global communications and cybersecurity.

Methods of Interception: A Technical Overview

The act of “tapping” an undersea cable is a formidable engineering challenge, far more complex than intercepting terrestrial internet traffic. The hostile environment, immense pressures, and sophisticated cable design necessitate highly specialized equipment and methods.

Direct Physical Access and Insertion

The most definitive method involves physically accessing the cable and inserting a device that can extract or inject data. This approach is fraught with significant technical and logistical difficulties.

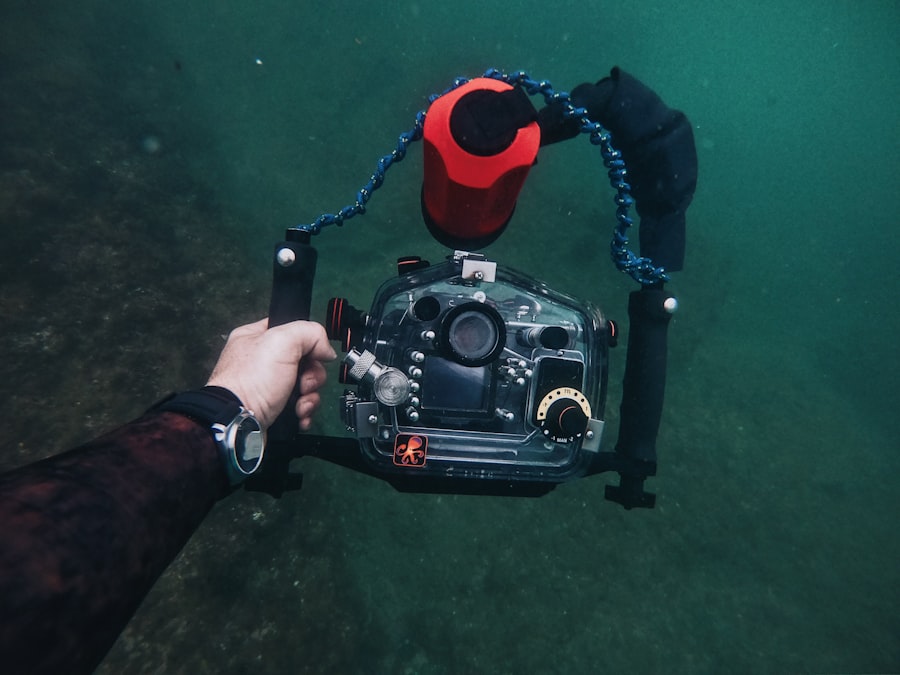

- Submersible Vehicles (ROVs/Submarines): Specialized remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) or manned deep-sea submersibles are required to locate, access, and manipulate cables on the seabed. These vehicles must be capable of operating at extreme depths and often for extended periods. Their deployment is a major logistical undertaking, akin to a covert deep-sea construction project.

- Cable Grapnels and Cutting: In extreme scenarios, a cable might be physically cut, and a “splice” inserted. This method is highly intrusive, risks service interruption, and is exceedingly difficult to conceal. Standard repair vessels would swiftly detect an outage, triggering a full investigation.

- Inductive Coupling (Non-Intrusive?): In theory, it might be possible to use inductive coupling to read faint electromagnetic signals emitted by the data pulses within the cable’s copper sheathing. However, given the optical nature of the data transmission and the extensive shielding, this method is widely considered impractical for extracting meaningful data from modern fiber optic cables. It is more relevant to older, purely electrical co-axial cables.

Optical Fiber Interception

Directly extracting data from the fiber optics involves siphoning off a minute portion of the light signal without disrupting the primary data flow.

- Fiber Bending and Micro-Borescopes: One theoretical method involves carefully bending the fiber to cause a microscopic amount of light to escape. This escaped light could then be captured by a specialized sensor. This is an extremely delicate operation, requiring precise control to avoid damaging the fiber and disrupting the signal. The “tap” must be imperceptibly small, and the optical loss introduced by the tap must be below the detection threshold of network monitoring systems.

- Splicing a “Coupler”: A more direct, but far more invasive method, would be to physically cut the fiber and insert an optical coupler. An optical coupler is a device that splits a light signal into two or more paths, sending a small percentage to a monitoring device and the rest along the original path. This method is comparable to inserting a “Y-splitter” in a garden hose, diverting a small stream without significantly impacting the main flow. However, any splice introduces optical loss, and if not precisely matched and expertly executed, it will be detectable via Optical Time Domain Reflectometer (OTDR) scans, which are regularly performed by cable operators to detect faults.

Signal Amplification and Repeaters

Undersea cables require signal amplification over long distances. Repeaters, spaced roughly every 50-100 kilometers, re-amplify the optical signal.

- Targeting Repeaters: Repeaters are critical points in the cable network. Accessing and modifying a repeater to divert a data stream could offer an interception point. However, repeaters are complex, sealed units designed to operate autonomously for decades under extreme pressure. Tampering with one without causing a detectable failure would be an extraordinary challenge. The power fed to repeaters also presents a significant engineering hurdle; drawing power for an interception device from the repeater’s limited supply would require intricate design and likely be detectable.

Challenges and Countermeasures

The physical and logical security of undersea cables is a continuous battle between those seeking to intercept data and those striving to protect it.

Environmental Hostility

The deep-ocean environment itself is a formidable deterrent to tapping.

- Depth and Pressure: Most cables lie thousands of meters deep, where pressures are immense and temperatures are near freezing. This demands highly specialized, robust equipment.

- Marine Life and Terrain: Canyons, ridges, and the occasional inquisitive deep-sea creature all pose challenges to submersibles and cable integrity. While unlikely to assist in tapping, marine life can inadvertently damage cables, requiring repairs and thus exposing them.

Detection and Monitoring

Cable operators employ sophisticated techniques to detect anomalies and damage.

- Optical Time Domain Reflectometry (OTDR): This technology sends laser pulses down the fiber and analyzes the reflections. Any change in the cable’s refractive index or a splice will create a noticeable reflection, allowing operators to pinpoint damage or unauthorized interventions with high precision.

- Power Monitoring: Repeaters are powered by electrical current sent down the cable from the landing stations. Any anomalous power draw by an unauthorized device attached to the cable would be detectable.

- Surveillance (for shallow water): In shallower, more accessible coastal areas, surveillance, including sonar, underwater drones, and patrols, can be employed to monitor cable routes for suspicious activity.

Encryption and Protocol Layer Security

Even if physical access is achieved, the data itself is protected at multiple layers.

- Physical Layer Encryption (Optical Layer Encryption): Advanced optical transport networks (OTN) increasingly employ encryption at the optical layer. This means that even if the light signal is diverted, the data pulses are cryptographically scrambled, rendering them unintelligible without the correct decryption keys.

- Networking Layer Encryption (IPsec): At the Internet Protocol (IP) layer, protocols like IPsec provide end-to-end encryption for specific traffic streams, protecting individual data packets.

- Application Layer Encryption (TLS/SSL): Most modern internet communication, such as web browsing, email, and instant messaging, is protected by Transport Layer Security (TLS) or Secure Sockets Layer (SSL). This ensures that even if traffic is intercepted, the content remains encrypted between the user’s device and the server.

- Traffic Obfuscation: Techniques like traffic shaping, fragmentation, and routing through multiple jurisdictions also make it harder to correlate intercepted data sets.

Historical Precedents and Known Incidents

The concept of tapping communications cables is not new. Its history offers valuable context to modern challenges.

Cold War Surveillance (Project Azorian, Ivy Bells)

During the Cold War, both the United States and the Soviet Union engaged in sophisticated underwater espionage.

- Project Azorian (mid-1970s): While not a cable tap, this CIA operation to recover a sunken Soviet submarine demonstrated the extraordinary lengths and technical prowess governments would employ for intelligence gathering in deep water. It showcases the feasibility of covert deep-sea operations, albeit of a massive scale.

- Operation Ivy Bells (1970s): This highly classified US Navy operation successfully tapped a Soviet undersea communications cable in the Sea of Okhotsk. US Navy submarines deployed sophisticated listening devices that attached to the cable, recording communications. This operation was one of the most successful intelligence gathering missions of the Cold War, demonstrating that cable tapping was not only theoretically possible but practically achievable with sufficient resources and expertise. The devices reportedly inductively coupled to the cable, extracting signals without physically breaking the optical fibers (which would not have been present in these older copper cables). The recordings were then retrieved periodically by submarines.

Modern Allegations and Speculations

In the wake of revelations from whistleblowers, public awareness of large-scale surveillance programs has increased.

- NSA and Submarine Cables: Documents leaked by Edward Snowden in 2013 provided details about programs like “MUSCULAR” and “PRISM,” which involved mass data collection. While these programs primarily focused on collecting data at major internet exchange points and collaboration with telecommunications companies (often at terrestrial landing stations), the possibility of direct access to undersea cables for intelligence agencies with vast resources remains a persistent concern. The sheer volume of data, even if encrypted, allows for “metadata” analysis (who communicates with whom, when, and how often), which itself can yield significant intelligence.

In exploring the intricate world of undersea cables, one might find it beneficial to read a related article that delves into the broader implications of these vital infrastructures on global communication and security. Understanding how to tap undersea cables can provide insights into the vulnerabilities and opportunities present in our interconnected world. For a deeper analysis, you can check out this informative piece on the topic at In The War Room, which discusses the strategic importance of these cables in modern warfare and intelligence gathering.

Ethical, Legal, and Political Implications

| Aspect | Description | Considerations | Potential Risks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Access Method | Physical tapping by divers or remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) | Requires specialized equipment and expertise | Damage to cable, detection by authorities |

| Signal Interception | Use of optical splitters to duplicate data signals | Must maintain signal integrity to avoid detection | Data loss, signal degradation |

| Location | Shallow coastal areas or landing stations | Easier access but higher risk of discovery | Legal consequences, physical hazards |

| Legal Status | Generally illegal without authorization | Requires government or owner consent | Criminal charges, international disputes |

| Technical Challenges | High pressure, waterproofing, signal encryption | Advanced technology needed to overcome | Failure to tap, equipment damage |

The act of tapping global communications infrastructure touches upon profound ethical, legal, and political issues.

Sovereignty and International Law

Undersea cables traverse international waters and land in numerous sovereign nations.

- Jurisdictional Ambiguity: The legal framework governing activities in international waters is complex. While nations have sovereign rights over their territorial waters, the high seas are considered international common space. Tapping a cable on the high seas, without the consent of the cable owner or the nations connected by it, could be viewed as a violation of international law.

- Interference with Peaceful Communication: International conventions generally advocate for the free flow of information and the protection of communication infrastructure. Deliberate interference could be seen as an act of aggression or cyberwarfare, depending on the intent and scale.

Privacy and Civil Liberties

Mass surveillance facilitated by cable tapping raises fundamental questions about individual privacy.

- Undermining Encryption: Efforts to intercept and decrypt data from cables, particularly if successful at scale, would erode the effectiveness of encryption, a cornerstone of secure digital communication.

- Due Process and Oversight: The covert nature of cable tapping operations often bypasses traditional legal oversight mechanisms and may lack transparency, leading to concerns about governmental overreach and potential abuse of power.

Economic and Geopolitical Consequences

The ability to tap or disable undersea cables carries significant geopolitical weight.

- Industrial Espionage: Nation-states and powerful corporations could use cable taps to gain economic advantages by stealing trade secrets, market data, and proprietary research.

- Cyberwarfare Capabilities: The capability to disrupt or sever undersea cables constitutes a powerful weapon in a cyberwarfare scenario, potentially crippling a nation’s economy and communications infrastructure. The physical destruction of cables has been attributed to state actors in the past, though direct “tapping” remains harder to prove.

- Trust and Stability: Any proven large-scale, unauthorized tapping of international cables can severely damage trust between nations and among global telecommunications partners, leading to retaliatory measures and increased tensions.

The Future of Undersea Cable Security

As global demand for data continues to surge, the importance and vulnerability of undersea cables will only increase.

Quantum Cryptography

Emerging technologies like quantum cryptography offer a potential paradigm shift in data security.

- Quantum Key Distribution (QKD): QKD allows for the secure exchange of cryptographic keys that are provably un-interceptable. While still largely in the research and development phase for long-haul applications, its deployment could render traditional interception methods obsolete for securing the key exchange. However, the data itself would still require encryption, and the challenges of integrating QKD into existing fiber networks are substantial.

Enhanced Physical Protection

Ongoing efforts focus on making cables even more resilient to physical interference.

- Burial and Armoring: Deeper burial into the seabed in critical shallow-water areas and more robust armoring continue to be refined.

- Advanced Sensors: Development of new types of embedded sensors within the cable itself that can detect subtle physical changes, vibrations, or light loss indicative of tampering.

International Cooperation and Norms

Establishing clear international norms and agreements for the protection of critical submarine infrastructure is paramount.

- Shared Responsibility: Given the interconnected nature of the network, the security of undersea cables is a shared responsibility among all nations. Collaborative efforts in intelligence sharing, joint patrols, and coordinated incident response are crucial.

- Transparency and Accountability: Greater transparency regarding surveillance capabilities and stricter accountability mechanisms for state actors could help build trust and prevent rogue operations.

The world’s undersea cables represent a marvel of engineering and a cornerstone of interconnectedness. While the allure of intercepting the vast flows of data they carry remains potent for various actors, the technical complexity, economic costs, and severe international implications surrounding such actions remain formidable. The ongoing arms race between those seeking to tap and those striving to protect represents a permanent feature of the digital landscape, pushing the boundaries of technology, ethics, and international relations.

FAQs

What are undersea cables and what is their purpose?

Undersea cables are fiber optic cables laid on the ocean floor that carry telecommunications signals, including internet, telephone, and data traffic, between continents and countries. They form the backbone of global communications.

Is tapping undersea cables legal?

Tapping undersea cables without authorization is generally illegal and considered a violation of international laws and agreements. Only authorized government agencies or organizations with proper legal permissions may conduct such activities for security or intelligence purposes.

How are undersea cables physically accessed for tapping?

Accessing undersea cables typically involves specialized ships and remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) that locate and retrieve the cable from the seabed. The cable can then be tapped by attaching devices that intercept data signals without disrupting the cable’s operation.

What technologies are used to tap undersea cables?

Tapping technologies include optical splitters and signal amplifiers that can extract a copy of the data transmitted through the fiber optic cables. These devices are designed to be stealthy and avoid detection by cable operators.

What are the risks and challenges involved in tapping undersea cables?

Tapping undersea cables is technically complex and risky due to the deep-sea environment, potential damage to the cable, and the need to avoid detection. Additionally, any disruption can cause significant communication outages, leading to legal and diplomatic consequences.