Here is an article about advancements in nuclear submarine engine technology, written in the third person with a factual style, devoid of overt flattery, and meeting the specified length and subtitle requirements:

Nuclear submarine propulsion systems, the silent hearts of underwater dominance, have undergone significant evolution since their inception. The inherent advantages of nuclear power—unlimited range and prolonged submerged endurance—have propelled its adoption by naval powers worldwide. These advancements are not mere incremental improvements but represent strategic leaps in engineering, safety, and operational capability, fundamentally reshaping naval warfare and power projection. The journey from early, cumbersome reactors to the sophisticated, compact, and highly resilient power plants of today is a testament to sustained innovation. The current landscape is defined by a relentless pursuit of efficiency, reduced acoustic signatures, and enhanced safety protocols, each element critical to maintaining a strategic edge in a complex and ever-changing global security environment.

The initial deployment of nuclear reactors aboard submarines marked a paradigm shift. Early designs, while revolutionary, were often bulky and required extensive shielding, posing significant design and operational challenges. The subsequent decades have witnessed a concerted effort to refine these designs, focusing on miniaturization, increased power density, and improved fuel utilization. This evolution can be broadly categorized into distinct generations, each building upon the lessons learned from its predecessors and introducing novel technological solutions. The goal has always been to extract more power from less space and less fissionable material, while simultaneously enhancing safety and reducing operational complexity.

Pressurized Water Reactors (PWRs)

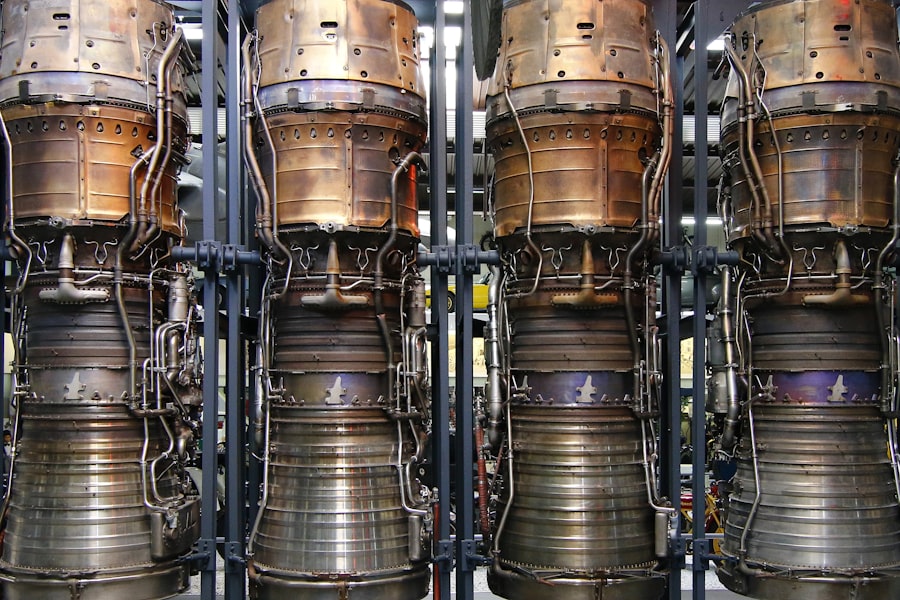

The Pressurized Water Reactor (PWR) has become the dominant architecture for nuclear submarine propulsion. This design, characterized by its use of ordinary water as both a coolant and a neutron moderator, offers a high degree of inherent safety and reliability. The primary coolant loop, containing water under high pressure, circulates through the reactor core, absorbing heat generated by nuclear fission. This heated water then transfers its thermal energy to a secondary loop through a heat exchanger, producing steam that drives the submarine’s turbines.

Early PWR Developments

The earliest PWRs for submarine applications, such as those found in the United States’ Nautilus class, were pilot projects that laid the groundwork for future designs. These reactors were robust but also relatively large and complex, with significant containment structures. Their primary function was to prove the viability of sustained underwater nuclear-powered operation, a feat previously unimaginable.

Modern PWR Innovations

Contemporary PWRs have significantly improved upon their predecessors. Innovations in fuel rod design, control rod mechanisms, and core geometry have led to increased power output and extended refueling intervals, often measured in years or even decades. Space-saving designs have become paramount, allowing for more compact reactor compartments that can be integrated into smaller submarine hulls, thereby enhancing maneuverability and reducing the submarine’s overall profile. The development of “one-loop” pressurized water reactors, which streamline the steam generation process by directly producing steam from the primary loop, further reduces complexity and potential leak points.

Advanced Reactor Concepts

Beyond the established PWR architecture, naval research and development has explored and, in some cases, implemented more advanced reactor concepts. These concepts aim to address specific limitations of PWRs or to exploit emerging technologies for even greater performance and safety benefits. While not as widespread as PWRs, these advanced designs represent the cutting edge of nuclear propulsion research.

Liquid Metal Fast Breeder Reactors (LMFBRs)

Liquid Metal Fast Breeder Reactors (LMFBRs) are a class of reactors capable of producing more fissile material than they consume, due to the use of fertile materials like depleted uranium in their fuel cycle. The use of liquid metal (typically sodium) as a coolant offers high thermal conductivity and a high boiling point, allowing for more efficient heat transfer and potentially smaller reactor sizes. However, the reactivity of sodium with air and water presents significant safety challenges that require rigorous engineering solutions. While some nations have experimented with LMFBRs for naval applications, their operational deployment has been limited, often due to the complexity of managing liquid metal coolants and the associated safety protocols.

Small Modular Reactors (SMRs)

Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) represent a promising avenue for future submarine propulsion. These are typically factory-fabricated, self-contained units that can be more easily integrated into new submarine designs. SMRs often incorporate passive safety features, relying on natural phenomena like gravity and convection to maintain cooling in the event of an emergency, thereby reducing reliance on active safety systems and operator intervention. Their modular nature could also facilitate easier maintenance and replacement, potentially reducing downtime and operational costs. However, the ultimate suitability of SMRs for the demanding environment of military submarines is still under active investigation and development.

Recent advancements in nuclear submarine engine technology have been pivotal in enhancing the efficiency and stealth capabilities of modern naval fleets. For a deeper understanding of the implications and innovations in this field, you can explore the article titled “The Future of Nuclear Propulsion in Submarines” available at this link. This article delves into the latest developments and future prospects of nuclear propulsion systems, shedding light on how they are shaping the future of underwater warfare.

Enhancements in Fuel and Core Technology

The heart of any nuclear reactor is its fuel. For submarine applications, this means developing fuel compositions and core configurations that maximize energy output, minimize waste, and ensure long operational life. Advances in metallurgy, chemistry, and nuclear physics have been instrumental in achieving these goals, transforming the reactor core from a consumable element into a highly engineered, long-duration power source.

Uranium Enrichment and Fuel Composition

The type and enrichment level of uranium used in submarine reactors are critical parameters. Higher enrichment levels allow for greater power density and longer core life, but also require more stringent handling and safety measures.

Enriched Uranium Isotopes

Submarine reactors typically utilize highly enriched uranium (HEU), often with uranium-235 enrichment levels of 20% or higher. This ensures a high neutron flux and sustained power generation for extended periods. Research continues into alternative fuel compositions that might offer similar performance with reduced proliferation concerns or enhanced safety characteristics.

Advanced Fuel Materials

Beyond traditional uranium dioxide (UO2) fuel, research into advanced fuel materials such as uranium-silicide or uranium-nitride compounds is exploring ways to increase the volumetric energy density of the fuel. This allows for a smaller core size for a given power output, or conversely, a higher power output from a standardized core size. These advanced materials are designed to withstand higher operating temperatures and radiation doses, contributing to longer fuel cycle lengths and improved overall efficiency.

Core Design and Neutron Economy

The physical arrangement of fuel elements within the reactor core, along with the materials used for moderation and reflection, directly impacts neutron economy – the balance between neutron production and neutron loss. Optimizing this balance is key to maximizing the efficiency of the nuclear reaction.

Fuel Element Geometry

Modern submarine reactor cores employ sophisticated fuel element geometries, such as pin-in-tube or plate-type designs, to maximize surface area for heat transfer and optimize neutron flux distribution. These designs are meticulously engineered to ensure uniform power generation across the core and to minimize the formation of “hot spots” that could compromise safety or efficiency.

Moderator and Reflector Materials

The choice of moderator (often demineralized water in PWRs) and reflector materials plays a crucial role in controlling the neutron population. Reflectors, typically made of materials like beryllium or stainless steel, surround the core and scatter returning neutrons back into the fuel, increasing their probability of causing fission. Advanced reflector designs and materials are continuously being investigated to further enhance neutron economy and improve overall reactor performance.

Improving Safety and Reliability

Safety is paramount in nuclear submarine operations. The unforgiving environment of the deep sea, coupled with the inherent risks associated with nuclear materials, necessitates a multi-layered approach to preventing accidents and ensuring the safe operation of the reactor. Recent advancements have focused on both passive safety features and sophisticated active monitoring and control systems.

Passive Safety Features

Passive safety systems rely on natural physical forces, such as gravity, convection, and natural circulation, to maintain reactor cooling and control in the event of an emergency, rather than requiring active intervention from pumps, operators, or external power sources.

Natural Circulation Cooling

The implementation of natural circulation cooling in reactor designs allows for the removal of decay heat even after the primary coolant pumps have been shut down. This significantly enhances safety by preventing the core from overheating during transient conditions or extended power loss scenarios. Designing for robust natural circulation requires careful consideration of flow paths, heat exchanger efficiency, and system geometry.

Core Catchers and Containment

While submarines have a different operational environment than land-based reactors, the concept of core catchers and robust containment structures remains relevant. These systems are designed to mitigate the consequences of a severe accident by physically containing released radioactive materials and preventing their dispersal. In a submarine context, this translates to highly resilient reactor compartments and specialized systems for managing any potential fuel breaches.

Active Monitoring and Control Systems

Complementing passive safety, advanced active monitoring and control systems provide real-time data and precise adjustments to ensure the reactor operates within its safe parameters.

Advanced Instrumentation and Diagnostics

Modern submarines are equipped with highly sophisticated instrumentation that continuously monitors key reactor parameters – temperature, pressure, neutron flux, coolant flow rates, and more. Advanced diagnostic algorithms analyze this data, identifying potential anomalies and predicting future performance, allowing for proactive adjustments and minimizing the risk of unexpected issues. This constant vigilance acts as a vigilant guardian overseeing the reactor’s heartbeat.

Digital Control Systems

The transition to digital control systems has revolutionized reactor management. These systems offer greater precision, flexibility, and processing power than their analog predecessors. They enable rapid responses to changing operational demands, optimize fuel burn-up, and facilitate integration with other submarine combat systems, creating a cohesive and intelligent operational platform.

Reducing Acoustic Signatures

The stealth capabilities of a nuclear submarine are directly linked to its acoustic signature – the noise it generates. Reducing this signature is a constant pursuit, as any detectable sound can betray the submarine’s position to enemy sonar. Nuclear propulsion systems, with their moving parts and heat transfer processes, are a significant source of noise.

Vibration Dampening and Isolation

Minimizing the transmission of vibrations from the propulsion machinery to the submarine’s hull is crucial for reducing its acoustic footprint.

Resilient Mounts and Bearings

The reactor, turbines, and associated pumps are mounted on specialized resilient systems designed to absorb and isolate vibrations. These systems can include advanced composite materials, pneumatic or hydraulic mounts, and precision-engineered bearings that minimize friction and noise. Think of them as shock absorbers for the submarine’s very heart.

Acoustic Shielding and Absorption Materials

Strategic placement of acoustic shielding and absorption materials within the reactor compartment further dampens the propagation of sound waves. These materials can include specialized composites, lead-lined panels, and porous absorbers that capture and dissipate acoustic energy, rendering the submarine a whisper in the ocean’s depths.

Turbine and Pump Efficiency

The efficiency of the turbines and pumps directly impacts their operational speed and, therefore, their noise generation.

Maglev Bearings and Hydrodynamic Design

The adoption of magnetic levitation (maglev) bearings in pumps and turbines reduces friction to near zero, significantly lowering noise and wear. Furthermore, advancements in hydrodynamic and aerodynamic design of impeller and blade profiles minimize turbulence and cavitation, two major sources of noise in fluid and gas handling systems.

Variable Speed Drives

The use of variable speed drives (VSDs) allows for precise control of motor speeds, enabling them to operate at optimal levels for fuel efficiency and reduced noise, rather than being fixed to a single, often louder, operating point. This agility in speed control is akin to a skilled musician modulating their tempo for a sublime performance.

Recent advancements in nuclear submarine engine technology have significantly enhanced the efficiency and stealth capabilities of modern naval vessels. These innovations not only improve propulsion systems but also extend the operational range of submarines, allowing them to remain submerged for longer periods. For a deeper understanding of the implications of these developments, you can explore a related article that discusses the strategic advantages offered by these technologies in contemporary warfare. Check it out here: In The War Room.

Future Directions and Innovations

| Metric | Description | Typical Value / Range | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reactor Type | Type of nuclear reactor used in submarine propulsion | Pressurized Water Reactor (PWR) | – |

| Thermal Power Output | Heat energy produced by the reactor core | 150 – 200 | MW (megawatts) |

| Propulsion Power Output | Mechanical power delivered to the propeller shaft | 30 – 60 | MW |

| Core Life | Operational lifespan of the reactor core before refueling | 10 – 25 | Years |

| Coolant Type | Fluid used to transfer heat from the reactor core | Light Water (H2O) | – |

| Fuel Type | Nuclear fuel used in the reactor | Enriched Uranium (20-90% U-235) | – |

| Maximum Speed | Top submerged speed achievable by the submarine | 25 – 35 | knots |

| Endurance | Maximum time submarine can operate without refueling | 20+ years | Years |

| Noise Level | Acoustic signature of the engine system | Very Low (classified) | dB (decibels) |

The advancement of nuclear submarine engine technology is not a static field. Ongoing research and development are continually pushing the boundaries, exploring new frontiers in efficiency, stealth, and operational longevity. The future promises even more sophisticated and capable propulsion systems.

Next-Generation Reactor Concepts

The pursuit of even higher performance and efficiency drives the exploration of entirely new reactor concepts.

Small, High-Power Density Reactors

The focus remains on developing reactors that are both smaller and capable of higher power outputs. This miniaturization allows for greater design flexibility for submarine hulls, potentially enabling faster, more maneuverable vessels or accommodating additional mission-critical equipment.

Extended Refueling Intervals and Operational Lifetimes

Significant research is directed towards extending the operational life of reactor cores, with the ultimate goal of achieving “life-of-ship” refueling. This would dramatically reduce the logistical burden and operational downtime associated with refueling, allowing submarines to remain on station for significantly longer periods.

Integration with Advanced Power Systems

The nuclear reactor is the primary power source, but future submarines will likely see more advanced integration with other power systems.

Advanced Battery Technology

While not a replacement for nuclear power, advanced battery technologies, such as solid-state batteries, could provide supplementary power for silent running at very low speeds or for emergency backup, further enhancing stealth and operational flexibility.

Improved Power Conversion Systems

The conversion of thermal energy from the reactor into mechanical or electrical power is also a subject of ongoing innovation. More efficient turbines, advanced thermoelectric generators, and novel power conversion cycles are being investigated to maximize the energy extracted from the nuclear heat source. This is akin to refining the engine’s transmission to ensure every ounce of power is efficiently delivered to the propeller.

The evolution of nuclear submarine engine technology represents a perpetual race against obsolescence and a relentless pursuit of enhanced capability. From the early, pioneering PWRs to the advanced concepts being explored today, each development has been driven by the exigencies of naval strategy and the imperative for sustained under-sea presence. The future of this technology holds the promise of even more silent, efficient, and enduring submarines, continuing to serve as potent symbols of national defense and maritime power projection.

FAQs

What type of reactor is commonly used in nuclear submarine engines?

Nuclear submarines typically use pressurized water reactors (PWRs) as their power source. These reactors use enriched uranium fuel and water under high pressure to generate heat, which produces steam to drive the submarine’s turbines.

How does a nuclear submarine engine differ from a conventional diesel engine?

A nuclear submarine engine uses nuclear fission to generate heat and produce steam for propulsion, allowing it to operate underwater for extended periods without refueling. In contrast, conventional diesel engines rely on combustion of fuel and require air, limiting underwater endurance.

What are the main advantages of nuclear propulsion in submarines?

Nuclear propulsion provides submarines with virtually unlimited underwater endurance, higher speeds, and greater operational range compared to conventional propulsion. It also reduces the need for frequent refueling and allows for quieter operation.

How is the nuclear reactor in a submarine kept safe during operation?

Submarine reactors are designed with multiple safety systems, including robust containment structures, automatic shutdown mechanisms, and continuous monitoring. The reactors operate at controlled temperatures and pressures, and crews are highly trained to manage any potential issues.

What kind of maintenance do nuclear submarine engines require?

Nuclear submarine engines require regular inspections, refueling (typically every 10-20 years), and maintenance of reactor components and associated systems. Maintenance is performed by specialized personnel and often requires the submarine to be docked at a naval shipyard.