Exploring the Depths: Underwater Vehicles

The boundless ocean, a realm of mystery and immense pressure, has long captivated the human imagination. While the surface of our planet is largely explored, its submerged expanses remain largely uncharted territory. To venture into these alien landscapes, humanity has developed a diverse array of underwater vehicles, tools that act as our eyes and extensions into the silent world beneath the waves. These machines, ranging from simple submersibles to sophisticated autonomous systems, are the key to unlocking the secrets held within the deep, enabling scientific discovery, resource exploration, and even the recovery of lost artifacts. Embarking on a journey into the underwater realm is akin to an astronaut venturing into the vacuum of space; it requires specialized equipment designed to withstand extreme conditions and facilitate exploration. The development and deployment of these underwater vehicles represent a significant leap in our capacity to understand and interact with the planet’s largest and least accessible biome.

The concept of venturing beneath the waves is not new. Early attempts at underwater exploration were rudimentary, driven by curiosity and a desire to exploit marine resources. The development of these initial submersibles laid the groundwork for the advanced vehicles we see today, marking humanity’s first tentative steps into the abyss.

Early Concepts and Inventions

The earliest documented ideas for submersible craft date back to the Renaissance. Leonardo da Vinci, in his notebooks, sketched designs for a diving apparatus that hinted at the possibility of underwater travel. However, it was during the Age of Sail that more practical attempts began to emerge. Inventors, often driven by military ambitions, sought to create vessels that could operate unseen beneath the surface. The “Turtle,” designed by David Bushnell during the American Revolutionary War, stands as a pioneering example. This human-powered submersible, though simple, demonstrated the fundamental principles of ballast control and maneuvering underwater. Its design was a far cry from modern submarines, resembling more a wooden barrel with propeller-like mechanisms, but it was a crucial early step in proving that controlled submersion was achievable.

The Rise of Military Submarines

The military applications of underwater technology rapidly outpaced civilian advancements in the early 20th century. The development of the diesel-electric submarine during World War I revolutionized naval warfare. These vessels, capable of operating on the surface with diesel engines and running submerged on electric motors, offered a stealthy and potent offensive capability. Their ability to launch torpedoes from unseen positions made them a formidable threat, and their evolution continued throughout World War II with further improvements in speed, depth, and armament. These military submarines, while primarily designed for combat, also contributed to a growing understanding of naval hydrodynamics and underwater operations, indirectly fueling broader submersible development.

Early Scientific and Exploratory Submersibles

While military submarines dominated the scene for decades, a parallel track of development focused on scientific and exploratory purposes. The need to observe marine life in its natural habitat, to study the ocean floor, and to conduct geological surveys spurred the creation of specialized submersibles. The “Bathysphere,” developed by Otis Barton and William Beebe in the early 1930s, was a significant advancement. This spherical dive chamber, lowered by cable from a surface vessel, allowed Beebe to descend to depths previously unimaginable, reaching over 800 meters. Though tethered and lacking independent propulsion, the Bathysphere provided the first direct visual insights into the deep-sea environment, revealing bizarre and fascinating creatures. These early scientific endeavors, though limited by technology, ignited a passion for deeper exploration.

Underwater vehicles have become increasingly important for various applications, including scientific research, military operations, and underwater exploration. For a deeper understanding of the advancements in this field, you can read a related article that discusses the latest innovations and technologies in underwater vehicles. To explore this topic further, visit this article for insights and developments that are shaping the future of underwater exploration.

Manned Submersibles: The Explorers’ Eyeglasses

Manned submersibles offer a unique advantage: the ability to place human observers directly into the underwater environment. These vessels are the direct descendants of early diving bells and submarines, refined to withstand immense pressures and provide a safe haven for their occupants. They are, in essence, our portable windows into a world otherwise inaccessible.

Bathyscaphes and Deep-Sea Research

Building upon the legacy of the Bathysphere, the bathyscaphe represented a significant leap in deep-sea exploration capability. Unlike tethered vehicles, bathyscaphes were free-diving submersibles. The most famous of these was the “Trieste,” a Swiss-designed vessel that, in 1960, carried Jacques Piccard and Don Walsh to the deepest known point of the Earth’s oceans, the Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench. Reaching a depth of nearly 11,000 meters, a feat equivalent to descending through the height of Mount Everest more than five times, the Trieste’s journey was a testament to human ingenuity and perseverance. The occupants of the Trieste, like deep-sea divers today, were essentially encased in a bubble of safety, observing the alien topography and life forms through thick portholes. This achievement, though it took place decades ago, remains a benchmark in human deep-sea exploration.

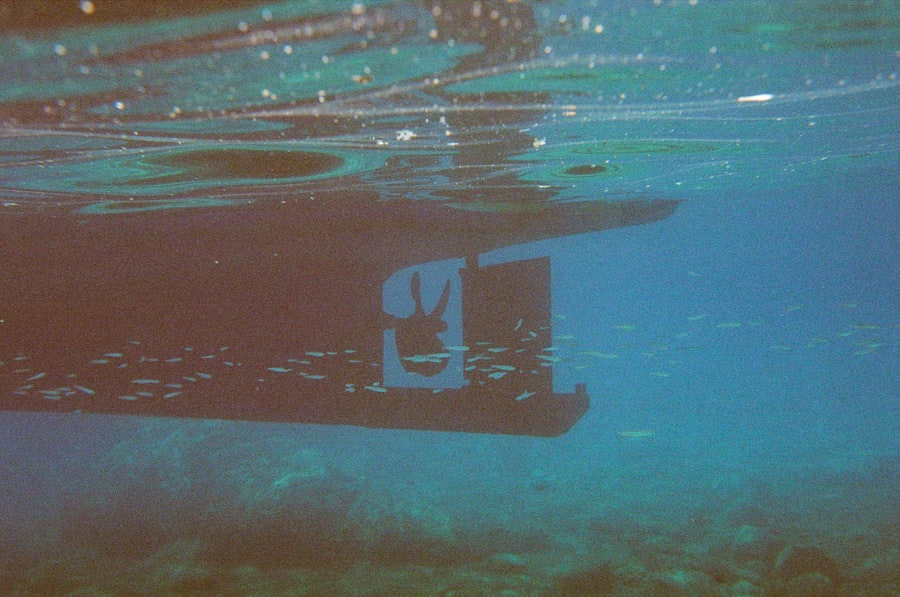

Tourist Submersibles and Commercial Applications

The allure of the underwater world has also translated into a burgeoning tourism industry and other commercial applications for manned submersibles. These vehicles are designed for shorter, shallower dives, typically around coral reefs, shipwrecks, and other points of interest. They prioritize passenger comfort and visibility, offering panoramic views through large acrylic domes. While not venturing into the crushing depths of scientific research vehicles, these tourist submersibles provide a safe and accessible way for the general public to experience the wonders of the marine environment. Beyond tourism, manned submersibles find applications in underwater construction, inspection of marine infrastructure (like oil rigs and pipelines), and salvage operations. Their ability to carry human operators allows for real-time decision-making and fine manipulation of equipment, crucial for tasks requiring precision.

The Limitations of Manned Exploration

Despite their invaluable contributions, manned submersibles face inherent limitations. The primary constraint is the physiology of the human body. The immense pressures of the deep ocean require robust, heavily reinforced pressure hulls, which are expensive to build and operate. Furthermore, human endurance is limited, and prolonged missions are challenging due to life support demands and the psychological impact of confined spaces. The risk associated with manned missions, though mitigated by advanced technology, is also a significant consideration. In the event of a catastrophic failure, the consequences for the crew can be dire. This has led to an increasing reliance on and development of unmanned systems.

Unmanned Underwater Vehicles (UUVs): The Silent Sentinels

As technology advanced, the focus began to shift towards unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs). These machines can operate in environments too hostile or too deep for human presence, providing a safer and often more cost-effective alternative for data collection and operations. They are the workhorses of modern oceanographic research and industrial applications, silently gathering information and performing tasks with remarkable precision.

Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs)

Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs) are tethered UUVs that are controlled from a surface vessel or a shore-based station. Aumbilical cable connects the ROV to the control station, supplying power and transmitting data and commands. This tether allows for continuous communication and power, enabling ROVs to perform extended missions with sophisticated payloads, including high-definition cameras, sonar systems, manipulators, and sampling equipment. ROVs are widely used in the offshore oil and gas industry for inspecting and maintaining subsea infrastructure, in scientific research for surveying the ocean floor and collecting samples, and in search and recovery operations. They are the robotic arms that extend humanity’s reach into the deep, allowing us to interact with the underwater world without risking human lives.

Key Components of ROVs

- Vehicle Body: The primary structure that houses all the components and provides buoyancy. Often made of advanced materials to withstand pressure.

- Propulsion System: Thrusters that provide maneuverability in multiple directions (forward, backward, up, down, and rotation).

- Sensors: A suite of instruments including cameras, sonar, depth sensors, temperature sensors, salinity sensors, and more, for gathering environmental data.

- Manipulators: Robotic arms or grippers used for tasks such as collecting samples, cutting cables, or opening valves.

- Lights and Cameras: Essential for visual inspection and data recording in the often-dark underwater environment.

- Umbilical Cable: The lifeline connecting the ROV to the surface, providing power and data transmission.

Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs)

Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs) are self-propelled UUVs that operate independently without a direct link to a surface vessel. They are programmed with a mission plan and navigate themselves using onboard sensors and navigation systems. AUVs are ideal for large-scale surveys, mapping the seafloor over vast areas, or conducting long-term environmental monitoring. Their autonomy allows them to cover more ground and operate for extended periods, making them invaluable for scientific research, underwater mapping, and defense applications.

Navigational and Sensing Capabilities of AUVs

AUVs employ a variety of sophisticated systems to navigate and gather data:

- Inertial Navigation Systems (INS): These systems use accelerometers and gyroscopes to track the AUV’s position, velocity, and orientation.

- Doppler Velocity Logs (DVL): These sonar systems measure the AUV’s velocity relative to the seafloor or the water column, aiding in precise positioning.

- Acoustic Positioning Systems: Beacons placed on the seafloor or on a surface vessel can be used to triangulate the AUV’s position.

- Sonar Systems: Side-scan sonar, multi-beam echo sounders, and sub-bottom profilers are used to map the seafloor topography and sub-surface structures.

- Environmental Sensors: Similar to ROVs, AUVs are equipped with sensors to measure parameters like temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen, and turbidity.

Hybrid Underwater Vehicles

Recognizing the strengths of both ROVs and AUVs, hybrid underwater vehicles have emerged. These vehicles can operate in both tethered and untethered modes, offering greater flexibility. They can be deployed as AUVs for broad surveys and then, if detailed inspection or manipulation is required, connected via an umbilical for ROV-like operations. This adaptability makes them versatile tools for a wide range of tasks, combining the endurance of autonomous systems with the precision of remote operation.

The Future of Underwater Exploration: Emerging Technologies

The field of underwater vehicle technology is in a constant state of evolution, driven by the relentless pursuit of deeper dives, longer missions, and more comprehensive data acquisition. Innovations in materials science, artificial intelligence, and energy efficiency are paving the way for the next generation of subsea explorers.

Advanced Materials and Deep-Sea Resilience

Pushing the boundaries of depth requires materials that can withstand incredible hydrostatic pressure. Researchers are exploring new composites, advanced alloys, and even novel structural designs to create hulls that are both strong and lightweight. For instance, ceramic materials are being investigated for their exceptional compressive strength, while the development of high-strength, low-density materials promises to improve buoyancy and reduce the power required for propulsion. This ongoing materials revolution is akin to building stronger and lighter space suits for astronauts, enabling them to venture further into the cosmos.

Artificial Intelligence and Swarm Robotics

Artificial intelligence (AI) is transforming the capabilities of UUVs. AI algorithms can enable AUVs to make real-time decisions, adapt to changing environmental conditions, and even collaborate with other UUVs in a “swarm.” Imagine a fleet of synchronized AUVs, acting as a single intelligent entity, mapping the ocean floor with unprecedented speed and efficiency. AI can also be used for autonomous data analysis, identifying patterns and anomalies in vast datasets that would be impossible for humans to process manually. This ability to learn and adapt is a game-changer for long-term, large-scale ocean monitoring.

Renewable Energy and Extended Mission Durations

Powering underwater vehicles for extended missions, especially in remote deep-sea locations, has always been a significant challenge. The development of more efficient battery technologies, harnessing of underwater currents for kinetic energy, and even advanced fuel cell technologies are all being explored to increase mission durations. For AUVs to become truly ubiquitous explorers, their endurance must be significantly enhanced, allowing them to embark on month-long scientific expeditions without the need for frequent resurfacing or resupply. This pursuit of energy independence is critical for unlocking the true potential of autonomous underwater exploration.

Underwater vehicles have revolutionized marine exploration and research, allowing scientists to access the depths of the ocean like never before. For those interested in learning more about the advancements in this field, a related article can be found at this link, which discusses the latest technologies and their implications for underwater missions. These innovations not only enhance our understanding of marine ecosystems but also play a crucial role in environmental monitoring and resource management.

Applications and Impact of Underwater Vehicles

| Vehicle Type | Maximum Depth (meters) | Typical Speed (knots) | Primary Use | Endurance (hours) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) | 6000 | 3 | Inspection, Research, Maintenance | 8-12 |

| Autonomous Underwater Vehicle (AUV) | 6000 | 4 | Mapping, Surveying, Data Collection | 24-48 |

| Submersible | 11000 | 2 | Deep Sea Exploration | 6-12 |

| Military Submarine | 500 | 30 | Defense, Surveillance | 720+ |

| Research Submarine | 4000 | 5 | Scientific Research | 24 |

The impact of underwater vehicles extends far beyond the realm of pure scientific curiosity. They are indispensable tools that drive innovation and provide critical services across a multitude of sectors, shaping our understanding of the planet and influencing our global economy.

Scientific Research and Discovery

Underwater vehicles are the primary means by which oceanographers, marine biologists, geologists, and climatologists gather data about the marine environment. They enable the study of deep-sea ecosystems, helping us understand biodiversity, the impact of climate change on oceans, and the potential for undiscovered life forms in extreme environments. The discovery of hydrothermal vents and the chemosynthetic ecosystems they support, for example, was facilitated by these technological marvels. These vehicles act as the eyes and hands for scientists, collecting samples of water, sediment, and marine organisms, and capturing imagery that reveals the secrets of the deep.

Studying Marine Life in Natural Habitats

For decades, our understanding of marine life was largely based on specimens caught in nets. Underwater vehicles, however, allow for unprecedented observation of animals in their natural habitats. Researchers can witness behaviors, social interactions, and feeding patterns that are impossible to observe in a laboratory setting. This provides a much richer and more accurate picture of marine ecology.

Geological and Geophysical Surveys

The ocean floor is a dynamic and complex geological landscape. Vehicles equipped with sonar and sub-bottom profiling systems can map the seafloor, identify geological formations, and study underwater volcanoes, trenches, and fault lines. This information is crucial for understanding plate tectonics, identifying potential earthquake and tsunami hazards, and discovering mineral resources.

Resource Exploration and Management

The ocean floor is a potential source of valuable resources, including oil, natural gas, and minerals. Underwater vehicles play a critical role in the exploration and extraction of these resources, particularly in deep-water environments. They are used for seismic surveys, drilling operations, and the inspection and maintenance of underwater pipelines and infrastructure. Responsible management of these resources also relies on the ability to monitor the environmental impact of extraction activities, a task also undertaken by UUVs.

Offshore Oil and Gas Industry

The modern offshore oil and gas industry is heavily reliant on underwater vehicles. ROVs are used for site surveys, wellhead inspections, pipeline laying and inspection, and emergency response. Their ability to operate in challenging conditions and at great depths makes them essential for maintaining the flow of energy resources.

Deep-Sea Mining Potential

As terrestrial resources become scarcer, the deep sea is being eyed as a potential source of minerals like manganese, cobalt, and rare earth elements. Underwater vehicles are crucial for surveying these deposits, assessing their economic viability, and developing the technologies for their sustainable extraction. However, the environmental implications of such operations are a significant concern and require careful study.

Maritime Safety and Security

Underwater vehicles are vital for ensuring maritime safety and security. They are used for locating and inspecting submerged hazards such as shipwrecks, mines, and debris that could pose a threat to navigation. In search and rescue operations, UUVs can be deployed to locate missing vessels or aircraft underwater. Defense forces also utilize specialized UUVs for mine countermeasures, surveillance, and reconnaissance.

Wreckage Recovery and Investigation

Investigating the causes of maritime disasters or recovering valuable artifacts from historical shipwrecks is often a complex and dangerous undertaking. Underwater vehicles, equipped with cameras and manipulators, can provide detailed imagery of wreckage, allowing investigators to piece together events and even retrieve artifacts with minimal disturbance. This has revolutionized maritime archaeology.

Mine Countermeasures (MCM)

The threat of underwater mines remains a significant concern in naval operations. Specialized UUVs are employed in mine countermeasures roles, using advanced sonar and detection systems to locate, identify, and neutralize these hidden dangers. Their deployment significantly reduces the risk to human divers and naval vessels.

Underwater vehicles represent a profound testament to humanity’s persistent drive to explore and understand its world. From the early, hesitant dives of primitive submersibles to the sophisticated autonomous systems of today, these machines have opened up vast frontiers of knowledge and practical application. As technology continues its relentless march forward, we can anticipate even more remarkable advancements, promising continued revelations from the ocean’s enigmatic depths and a deeper connection to the blue heart of our planet.

FAQs

What are underwater vehicles?

Underwater vehicles are machines designed to operate below the surface of water. They can be manned or unmanned and are used for various purposes such as exploration, research, military operations, and underwater construction.

What types of underwater vehicles exist?

There are several types of underwater vehicles, including submarines, remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), and human-occupied vehicles (HOVs). Each type serves different functions depending on the mission requirements.

How do underwater vehicles navigate underwater?

Underwater vehicles use a combination of sonar, GPS (when near the surface), inertial navigation systems, and sometimes acoustic positioning systems to navigate and maintain their course underwater.

What are common uses of underwater vehicles?

Underwater vehicles are commonly used for scientific research, underwater archaeology, oil and gas exploration, military surveillance, search and rescue missions, and environmental monitoring.

What challenges do underwater vehicles face?

Underwater vehicles face challenges such as high pressure at depth, limited communication capabilities, navigation difficulties, energy constraints, and the need for robust materials to withstand harsh underwater environments.