The Cold War, a period of geopolitical tension that spanned five decades, was defined by a multifaceted struggle for dominance between the United States and the Soviet Union. While nuclear arsenals and ICBMs often dominated public discourse, a silent battle unfolded beneath the waves: the relentless pursuit and evasion of submarines. Underwater acoustic surveillance, a technological and strategic cornerstone of this subterranean conflict, played a pivotal role in shaping naval doctrine, intelligence gathering, and the delicate balance of power. This article will delve into the methods, technologies, and implications of underwater acoustic surveillance of Soviet submarines, examining its evolution and enduring legacy.

The imperative to detect and track submarines predates the Cold War, emerging prominently during World War I and II with the advent of U-boat warfare. However, the post-war era, colored by the advent of nuclear-powered submarines and ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs), dramatically intensified this need. These new Soviet vessels, capable of prolonged underwater endurance, high speeds, and carrying world-ending ordnance, presented an unprecedented strategic threat. The vastness and opacity of the ocean, a “liquid desert” to conventional detection methods, necessitated a specialized approach.

Early Detection Methods: From Hydrophones to Sonar

Initial attempts at underwater acoustic surveillance relied on passive hydrophones – simply glorified underwater microphones – that listened for the sounds of a submarine’s machinery. These basic instruments, however, suffered from limitations in range, directionality, and the overwhelming noise of the ocean itself. The breakthrough came with the development of sonar (SOund NAvigation and Ranging), both passive and active.

Passive Sonar: Listening for Whispers

Passive sonar, at its core, involved listening to the acoustic emanations of a submarine. These emanations – propeller cavitation, engine noise, pump operation, and even crew activities – provided a unique acoustic “fingerprint.” The ability to identify these individual acoustic signatures became paramount. The challenge lay in distinguishing these faint signals from the cacophony of marine life, seismic activity, and surface ship traffic.

Active Sonar: Sending Out a Shout

Active sonar, on the other hand, involved emitting a pulse of sound and listening for an echo. The time it took for the echo to return, and its direction, allowed for the calculation of an object’s range and bearing. While more definitive in detection, active sonar had a significant drawback: it revealed the position of the emitting vessel, effectively turning the hunter into the hunted. Its use was often a desperate measure or a decisive engagement tactic rather than a continuous surveillance tool.

For those interested in the intricacies of underwater acoustic surveillance, particularly in the context of monitoring Soviet submarines during the Cold War, a related article can be found at In the War Room. This article delves into the technological advancements and strategic implications of acoustic detection methods, providing a comprehensive overview of how these techniques shaped naval warfare and intelligence gathering during a pivotal era in history.

The SOSUS Network: An Underwater Tripwire

The most ambitious and enduring manifestation of underwater acoustic surveillance was the Sound Surveillance System, or SOSUS. Conceived in the late 1940s and deployed throughout the 1950s and beyond, SOSUS was a network of seafloor-mounted hydrophone arrays designed to detect and track Soviet submarines as they transited critical choke points and patrol areas.

Design and Deployment: A Web Beneath the Waves

The SOSUS system comprised long arrays of hydrophones laid on the continental shelf and abyssal plains, primarily in the North Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. These arrays were connected to shore processing stations via heavily armored underwater cables. The strategic placement of these arrays aimed to exploit areas where Soviet submarines were most likely to pass, such as the Greenland-Iceland-United Kingdom (GIUK) Gap.

The GIUK Gap: A Strategic Bottleneck

The GIUK Gap represented a geographical choke point, a maritime “strait gate” through which Soviet submarines from their northern fleets would have to pass to reach the open Atlantic. SOSUS arrays in this region were designed to act as an acoustic barrier, providing early warning of Soviet submarine deployments and movements towards US and NATO shipping lanes and coasts.

Data Processing and Analysis: Turning Noise into Intelligence

The sheer volume of acoustic data collected by SOSUS was immense. Shore stations, manned by highly trained personnel, utilized sophisticated signal processing techniques to filter out ambient noise and isolate the distinctive sounds of Soviet submarines. This involved spectral analysis, pattern recognition, and ultimately, human intuition and experience. The processed data provided invaluable intelligence on Soviet submarine numbers, deployment patterns, and operational characteristics.

Impact and Limitations of SOSUS

SOSUS proved to be remarkably effective, providing the United States and its allies with an unprecedented level of awareness of Soviet submarine activity. It transformed naval surveillance, shifting from sporadic contact to sustained, wide-area monitoring. However, SOSUS was not without its limitations. It was primarily a passive system, susceptible to environmental noise and the ever-improving acoustic stealth of Soviet submarines.

Evolving Threats and Countermeasures: The Silent Arms Race

The development and deployment of sophisticated Soviet submarines, particularly Quiet Revolution-era vessels like the Project 671RTM “Viktor III” and Project 971 “Akula” class, forced a continuous evolution in underwater acoustic surveillance. This became a silent arms race, a constant push and pull between the creators of silence and the listeners.

The Quiet Revolution: Soviet Advances in Stealth

Soviet submarine designers dedicated significant resources to reducing radiated noise, employing advanced anechoic coatings, isolating machinery on resilient mounts, perfecting propeller designs, and utilizing natural circulation reactors. These innovations made detection increasingly challenging, pushing the boundaries of acoustic surveillance technology.

Anechoic Coatings: Absorbing Sound

Anechoic tiles, a rubber-like material applied to submarine hulls, were designed to absorb active sonar pings and reduce the submarine’s own radiated noise. This technological leap presented a significant hurdle for both active and passive sonar systems.

Machinery Isolation and Propeller Design: Mitigating Internal Noise

By isolating noisy machinery from the hull with shock absorbers and designing highly efficient, quiet propellers, Soviet engineers significantly reduced the acoustic “footprint” of their submarines. This forced passive sonar systems to become even more sensitive and sophisticated in their analysis.

Advancements in Detection: Towed Arrays and Maritime Patrol Aircraft

In response to these advances, the West developed new and enhanced detection technologies. Towed array sonar systems and improvements in maritime patrol aircraft (MPA) became crucial elements of the surveillance effort.

Towed Array Sonar: Long Ears for the Hunter

Towed array sonar systems, long cables fitted with hydrophones streamed behind surface ships and submarines, offered enhanced detection capabilities. Their length provided superior directionality and signal processing capabilities, allowing them to detect fainter signals over longer ranges. They acted as a ship’s “long ears,” extending its acoustic reach far beyond its own hull.

Maritime Patrol Aircraft (MPA): Eyes and Ears from Above

Aircraft such as the P-3 Orion, equipped with sonobuoys (disposable sonar devices ejected from the aircraft) and magnetic anomaly detectors (MAD), played a vital role in localizing and tracking submarines once they were initially detected. The sonobuoys, deployed in patterns, could form temporary acoustic barriers or pinpoint a submarine’s location through triangulation. MAD, while limited in range, could detect anomalies in the Earth’s magnetic field caused by the presence of a large metallic object like a submarine.

The Human Element: Training and Intelligence Fusion

Beyond the hardware and software, the human element remained critical. Highly skilled acousticians, analysts, and intelligence officers were the “brains” behind the “ears” of the surveillance network. Their ability to interpret complex acoustic data, understand Soviet doctrine, and synthesize disparate pieces of information was indispensable.

Acoustic Interpretation: The Art and Science of Listening

Acousticians underwent rigorous training to distinguish the subtle nuances of submarine sounds. They learned to identify specific classes of submarines by the unique pitch and rhythm of their machinery, the whir of their pumps, or the characteristic blade effect of their propellers. This required a keen ear, extensive knowledge, and often, an intuitive understanding of the underwater environment.

Acoustic Signatures: Submarine Fingerprints

Each submarine possessed a distinct acoustic signature, a unique pattern of sounds that allowed for its identification. Think of it like a human fingerprint, but for a mechanical leviathan. The compilation and analysis of these signatures formed a vast database of intelligence, crucial for tracking and identifying individual vessels.

Intelligence Fusion: Connecting the Dots

Acoustic data was rarely viewed in isolation. It was integrated with other intelligence sources – satellite imagery, electronic intelligence (ELINT), human intelligence (HUMINT), and open-source information – to create a comprehensive picture of Soviet submarine operations. This intelligence fusion, akin to assembling fragments of a mosaic, allowed analysts to predict future movements, understand strategic intentions, and counter potential threats.

Underwater acoustic surveillance of Soviet submarines has been a critical aspect of naval strategy during the Cold War, as it allowed for the monitoring of submarine movements and capabilities. For a deeper understanding of the technological advancements and methodologies used in this field, you can explore a related article that discusses various surveillance techniques and their implications in modern warfare. This insightful piece can be found here.

Legacy and Beyond: From Cold War to Modern Surveillance

| Metric | Description | Typical Values | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency Range | Acoustic frequencies used for detection and monitoring | 10 Hz to 10 kHz | Lower frequencies travel farther underwater, enabling long-range detection |

| Detection Range | Maximum distance at which Soviet submarines can be detected | Up to 100 km (varies by environment and equipment) | Determines surveillance coverage area |

| Hydrophone Array Length | Length of underwater microphone arrays used in surveillance | Several kilometers (e.g., SOSUS arrays ~10 km) | Long arrays improve directional resolution and sensitivity |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | Ratio of submarine acoustic signal strength to background noise | Typically 10-30 dB for effective detection | Higher SNR improves detection reliability |

| Submarine Acoustic Signature | Characteristic noise emitted by Soviet submarines | Propeller cavitation, machinery noise, hull flow noise | Used to classify and identify submarine classes |

| Ambient Noise Level | Background ocean noise affecting detection | 50-70 dB re 1 µPa (varies with sea state) | Limits minimum detectable signal level |

| Processing Time | Time required to analyze acoustic data and identify targets | Seconds to minutes | Faster processing enables timely response |

| False Alarm Rate | Frequency of incorrect submarine detections | Less than 5% in optimized systems | Critical for operational reliability |

The end of the Cold War did not diminish the importance of underwater acoustic surveillance. Instead, its methodologies and technologies continue to evolve, adapting to new threats and challenges. The legacy of the Cold War’s silent struggle beneath the waves profoundly shaped modern naval doctrine and intelligence gathering.

Challenges of the Post-Cold War Era

The proliferation of advanced submarines among various nations, including those with less transparent intentions, presents new challenges. The rise of quiet diesel-electric submarines, capable of operating in shallow, acoustically complex coastal waters, requires further innovation in detection.

The Rise of Unmanned Underwater Vehicles (UUVs)

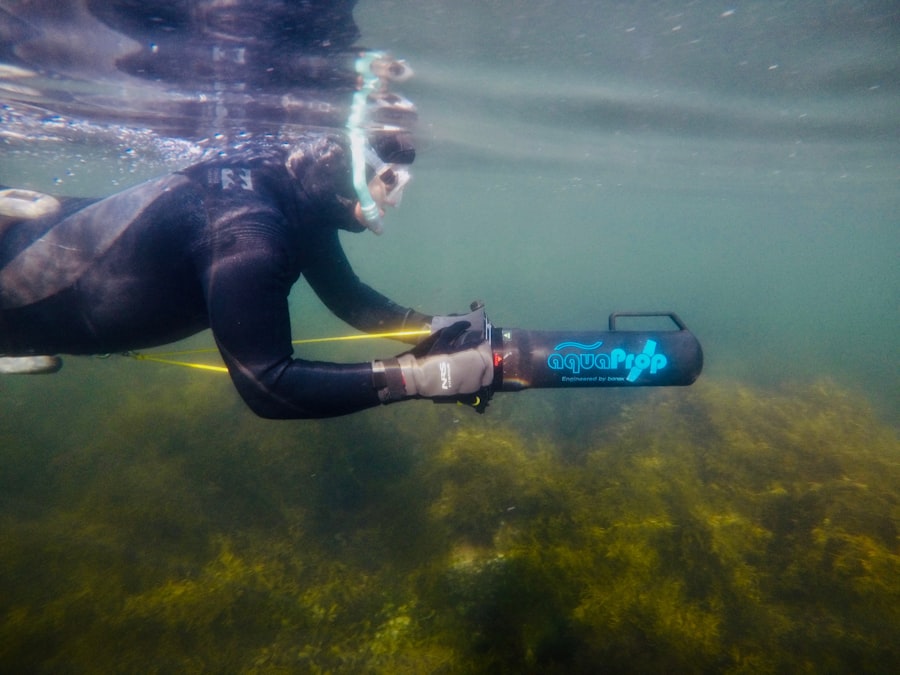

Unmanned Underwater Vehicles (UUVs), both autonomous and remotely operated, are increasingly being deployed for surveillance tasks. These platforms can carry sophisticated sonar payloads, operate for extended periods, and venture into areas too dangerous or tedious for manned vessels, acting as persistent robotic “eavesdroppers.”

The Enduring Importance of Acoustic Stealth

The emphasis on acoustic stealth for submarines remains paramount today. Nations continue to invest heavily in reducing their submarines’ acoustic signatures, recognizing that in the underwater domain, silence is often the most potent weapon. Conversely, the relentless pursuit of accurate and long-range acoustic detection remains a top priority for naval powers around the world. The ocean, despite its vastness, has become a finely tuned instrument, constantly listening, constantly striving to peel back the veil of silence that shrouds its most formidable denizens. The underwater acoustic surveillance of Soviet submarines during the Cold War serves as a stark reminder of the ingenuity, dedication, and immense resources committed to a silent but critical aspect of global security.

WATCH NOW▶️ Soviet submarine acoustic signatures

FAQs

What was the purpose of underwater acoustic surveillance of Soviet submarines?

Underwater acoustic surveillance was used to detect, track, and monitor Soviet submarines during the Cold War. This helped NATO and allied forces maintain strategic awareness and ensure maritime security.

How did underwater acoustic surveillance systems work?

These systems used hydrophones and sonar arrays placed on the ocean floor or deployed from ships and aircraft to capture sound waves emitted by submarines. By analyzing these acoustic signals, operators could identify submarine movements and classify their types.

What technologies were commonly used in underwater acoustic surveillance?

Key technologies included passive sonar systems, which listen for sounds without emitting signals, and active sonar, which sends out sound pulses and listens for echoes. The SOSUS (Sound Surveillance System) network was a prominent example of a passive underwater acoustic surveillance system.

Why were Soviet submarines specifically targeted for acoustic surveillance?

Soviet submarines represented a significant strategic threat during the Cold War due to their nuclear capabilities and potential to disrupt NATO naval operations. Monitoring their movements was crucial for maintaining a balance of power and early warning of possible attacks.

What impact did underwater acoustic surveillance have on naval strategy?

Underwater acoustic surveillance enhanced anti-submarine warfare capabilities, allowing navies to detect and counter submarine threats more effectively. It influenced submarine design, tactics, and the development of quieter submarines to evade detection.