You stand at the edge of the ocean, the vast, blue expanse stretching before you. The surface waves crash against the shore, a familiar sound that hints at the immense volume of water beyond. But what lies beneath that shimmering skin? It’s a realm largely unseen, a three-dimensional world where light attenuates rapidly, and a different kind of perception reigns supreme: sound. This is the realm of underwater acoustics, a field that unlocks the secrets of the marine environment through the study of sound.

Just as sight is your primary sense in the terrestrial world, sound is the ocean’s pervasive language. It travels further, faster, and with less distortion than in air, acting as the eyes and ears for countless marine organisms. For you, the explorer, understanding underwater acoustics is akin to learning a new language, one that can reveal the intricate workings of ecosystems, the silent migrations of whales, and the geological whispers of the seafloor.

The Nature of Sound in Water

You might assume sound behaves similarly in water as it does in air, but this is a fundamental misconception. Water is a denser medium than air, and this increased density significantly impacts how sound propagates.

Speed of Sound

The speed of sound is not a constant; it varies depending on the properties of the medium through which it travels. In water, the speed of sound is considerably greater than in air, typically around 1,500 meters per second, compared to about 343 meters per second in air. This difference is a direct consequence of water’s density and bulk modulus (a measure of its resistance to compression). Imagine trying to push a light ball through air versus a heavy cannonball through water; the cannonball, though heavier, resists being compressed more strongly, allowing sound waves to travel through it more efficiently.

Transmission and Attenuation

Sound travels remarkably well underwater, a boon for communication and detection. However, it is not immune to loss of energy, a process known as attenuation.

Factors Affecting Attenuation

Attenuating forces are like slow leaks in a dam, gradually diminishing the sound’s power.

Frequency Dependence

Higher frequency sounds are attenuated more rapidly than lower frequency sounds. This is why whale songs, which are typically low-frequency, can travel for hundreds or even thousands of kilometers, while the sounds of a snapping shrimp, which are high-frequency, are more localized. You can think of low frequencies as broad, powerful waves that roll over obstacles, while high frequencies are like delicate ripples that are easily dissipated.

Temperature, Pressure, and Salinity

These are the three titans that influence how sound behaves underwater. Temperature, in particular, plays a significant role, with warmer water generally leading to faster sound speeds. Pressure, which increases with depth, also increases sound speed. Salinity, the salt content of the water, has a less pronounced but still measurable effect. These variables combine to create a complex tapestry of sound propagation, often referred to as the “soundscape” of a particular ocean region.

Absorption and Scattering

Attenuation is further influenced by absorption, where the sound energy is converted into heat, and scattering, where the sound waves are deflected in various directions by the unevenness of the seafloor, marine life, or even tiny bubbles in the water. Imagine shining a flashlight into a murky pool; some light is absorbed by the water itself, and some is scattered by suspended particles, making it difficult to see distant objects. Sound operates under similar principles.

The Ocean as a Resonating Chamber

The ocean is not a uniform, homogenous medium. Its physical boundaries – the surface and the seafloor – and its internal structure act as natural reflectors and refractors, shaping the path of sound waves.

Sound Channels

Certain conditions create “sound channels,” pathways where sound can travel with minimal loss over vast distances. The deep sound channel, also known as the SOFAR (Sound Fixing and Ranging) channel, is a prime example. Here, at a specific depth where pressure and temperature effects balance out, the sound speed is at its minimum. Sound waves entering this channel tend to remain confined within it, much like a marble rolling in a long, curved trough, allowing them to propagate for immense distances.

Reflection and Refraction

The ocean’s boundaries are like mirrors for sound. The seafloor, depending on its composition (rocky, sandy, or muddy), will reflect sound waves differently. Similarly, the ocean surface can reflect sound, leading to complex interference patterns. Refraction, the bending of sound waves as they pass through layers of water with different sound speeds, is another crucial phenomenon. This bending can channel sound in unexpected directions or create “shadow zones” where sound is significantly attenuated.

Marine Life and Underwater Acoustics

Few areas of underwater acoustics are as captivating as the study of how marine animals use sound. For many species, sound is their primary sensory modality, essential for survival.

Communication and Navigation

From the basso profundo of whales to the clicks of dolphins and the grunts of fish, the ocean is alive with acoustic activity.

Cetacean Vocalizations

Whales and dolphins, or cetaceans, are renowned for their complex vocalizations. Whistles, clicks, pulsed calls, and songs are all employed for a variety of purposes.

- Echolocation: Dolphins and some toothed whales use echolocation, emitting clicks and interpreting the returning echoes to navigate, find prey, and understand their surroundings. It’s like sending out a sonar ping and building a detailed mental map from the returning signals.

- Social Communication: Whales sing elaborate songs, thought to be used for attracting mates, establishing territory, or maintaining social bonds. These songs can be incredibly intricate and change over time and across populations.

- Navigation: Low-frequency calls from baleen whales can travel hundreds of miles, potentially aiding in long-distance navigation across vast ocean basins.

Fish Sounds

You might be surprised to learn that fish make noise. Many species produce sounds through a variety of mechanisms, including vibrating their swim bladders or rubbing their bones together. These sounds are used for mating, territorial defense, and predator avoidance.

Invertebrate Sounds

Even some invertebrates, like shrimp and lobsters, produce sounds. Snapping shrimp, for instance, create a loud “snap” with their claws, which forms a cavitation bubble that implodes, generating a broadband click. This serves as both a defense mechanism and a hunting strategy.

The Impact of Anthropogenic Noise

While the ocean teems with natural sounds, a growing concern is the increasing level of anthropogenic (human-made) noise pollution. This noise can significantly impact marine life, disrupting communication, feeding, and even causing physical harm.

Shipping Noise

The constant hum of commercial shipping is a pervasive source of low-frequency noise in the ocean. This can mask the communication of whales and other marine mammals, making it harder for them to find mates or navigate.

Seismic Surveys

The oil and gas industry uses powerful airguns to generate seismic waves that penetrate the seafloor to map geological structures. These blasts are incredibly loud and can cause hearing damage and behavioral changes in marine animals.

Sonar

Naval sonar systems, used for detecting submarines, can also be extremely loud and have been linked to strandings and injuries in marine mammals.

Applications of Underwater Acoustics

The study of underwater acoustics is not merely an academic pursuit; it has a wide range of practical applications that benefit humanity.

Marine Research and Exploration

Understanding how sound travels underwater is fundamental to many marine research endeavors.

Hydroacoustics for Biomass Estimation

Hydroacoustic surveys are used to estimate the abundance and distribution of fish populations. By emitting sound pulses and analyzing the echoes from fish schools, scientists can determine the size and density of these aggregations, providing crucial data for fisheries management.

Seafloor Mapping and Characterization

Sonar systems are employed to create detailed maps of the seafloor. Different types of sonar can differentiate between various bottom types (e.g., sand, rock, mud) and identify underwater features like shipwrecks or geological formations.

Marine Mammal Monitoring

Acoustic monitoring is a non-intrusive method for studying marine mammals. Passive acoustic monitoring (PAM) uses underwater microphones (hydrophones) to detect and identify vocalizations, allowing researchers to track their presence, distribution, and behavior over time.

Navigation and Communication

Historically and currently, underwater acoustics plays a vital role in navigation and communication.

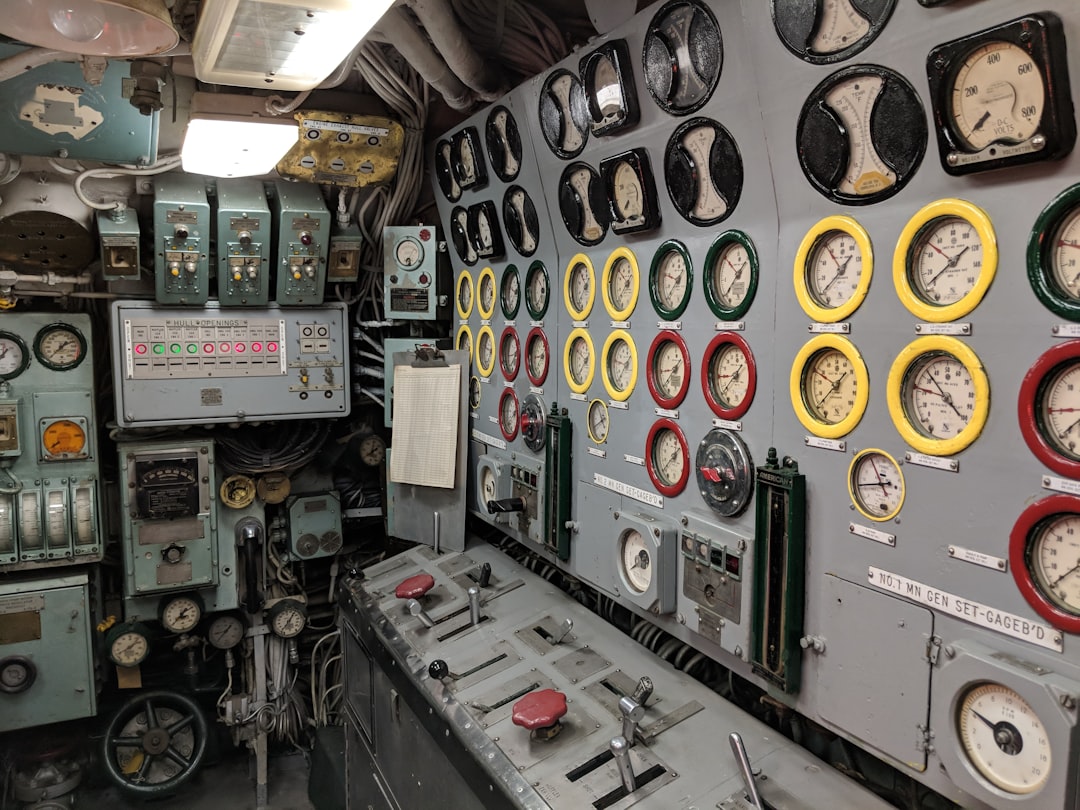

Sonar Systems

You encounter sonar in various forms, from the navigation systems on ships to the depth sounders that help fishermen locate fish. Military sonar systems are designed for the detection of submarines and other underwater objects.

Underwater Communication

While challenging, underwater acoustic communication is used for various purposes, including communicating with subsea vehicles, divers, and underwater sensors. The limited bandwidth and potential for interference make it a complex engineering problem.

Defense and Security

The military applications of underwater acoustics are extensive, particularly in naval warfare.

Submarine Detection

Sonar is the primary tool for detecting submarines. Active sonar emits sound pulses and listens for echoes, while passive sonar listens for the sounds made by submarines themselves.

Mine Detection

Acoustic sensors are used to detect underwater mines, helping to keep shipping lanes safe.

The Future of Underwater Acoustics

As technology advances and our understanding of the ocean deepens, the field of underwater acoustics is poised for significant growth.

Advanced Signal Processing

Developing sophisticated algorithms to analyze complex underwater acoustic data is crucial. This includes techniques for distinguishing between biological and man-made sounds, identifying individual animals, and improving the accuracy of sonar systems.

Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs)

AUVs equipped with advanced acoustic sensors are becoming increasingly important for exploring remote and hazardous underwater environments. These robots can collect vast amounts of data over long periods, providing new insights into the ocean’s acoustics.

Addressing Noise Pollution

A critical future direction is the development of strategies to mitigate anthropogenic noise pollution in the ocean. This involves quieter ship designs, regulations on sonar use, and further research into the impact of noise on marine life.

Interdisciplinary Collaboration

The challenges and opportunities in underwater acoustics often require collaboration between oceanographers, biologists, engineers, physicists, and computer scientists. This interdisciplinary approach is essential for tackling complex issues and driving innovation.

You have only scratched the surface of this remarkable field. The world of underwater acoustics is a testament to the power of sound to illuminate the unseen, connect us with other species, and unlock the mysteries of our planet’s largest contiguous ecosystem. As you continue your exploration, remember that beneath the waves, a silent symphony plays, waiting to be heard and understood.

WATCH NOW▶️ Submarine detection technology history

FAQs

What is underwater acoustics?

Underwater acoustics is the study of sound propagation in water and the interaction of sound waves with the underwater environment. It involves understanding how sound travels through water, how it is absorbed, reflected, and scattered, and how it can be used for communication, navigation, and detection.

How does sound travel differently underwater compared to air?

Sound travels faster and farther underwater than in air because water is denser and less compressible. The speed of sound in seawater is approximately 1500 meters per second, which is about four times faster than in air. Additionally, sound attenuation is lower in water, allowing sound waves to propagate over long distances.

What are common applications of underwater acoustics?

Underwater acoustics is used in various applications including sonar for detecting and locating objects underwater, underwater communication systems, marine biology studies, oceanographic research, and environmental monitoring. It is also essential for submarine navigation and underwater vehicle operation.

What factors affect sound propagation underwater?

Several factors influence underwater sound propagation, including water temperature, salinity, pressure (depth), and the presence of obstacles or marine life. These factors affect the speed of sound and can cause refraction, scattering, and absorption of sound waves.

What is sonar and how is it related to underwater acoustics?

Sonar (Sound Navigation and Ranging) is a technology that uses underwater acoustics to detect, locate, and identify objects by emitting sound pulses and analyzing the echoes that return. It is widely used in navigation, fishing, underwater exploration, and military applications.