You stand on the edge of a vast, blue expanse, a surface that hints at mysteries far below. Oceanography, your window into these submerged realms, is not merely an academic pursuit; it’s a crucial exploration with profound impacts on your very existence. This discipline, a multifaceted study of the oceans, delves into their physical, chemical, geological, and biological aspects, revealing how these colossal bodies of water shape your planet and influence your life in ways you may not have fully considered.

The ocean covers over 70% of Earth’s surface, a colossal heart pumping life and driving the planet’s climate. To understand oceanography is to understand a fundamental organ of your world, a system as complex and vital as any biological entity. Its currents are the planet’s arteries, its deep trenches, its hidden arteries, and its unseen inhabitants, the microscopic architects of your atmosphere.

The Foundational Pillars of Oceanography

Oceanography itself is not a monolithic entity. It is a tapestry woven from diverse threads, each contributing to a comprehensive understanding of the marine environment. You can visualize these as distinct, yet interconnected, chambers within the grand edifice of oceanographic study.

Physical Oceanography: The Ocean’s Pulse

Imagine the ocean as a giant, dynamic engine. Physical oceanography is the discipline that studies its mechanics, the forces that drive its movements, and the patterns that emerge from this ceaseless activity. You can think of it as the study of the ocean’s heartbeat, its breathing, and the intricate pathways of its circulation.

Currents: The Ocean’s Conveyor Belt

You witness the surface manifestations of currents in the predictable flow of rivers and the predictable drift of debris. But beneath the waves, a far more complex system of currents operates, a global conveyor belt that redistributes heat, nutrients, and gases. These currents, driven by a delicate interplay of wind, temperature, and salinity, exert a significant influence on your planet’s climate. The Gulf Stream, for instance, a powerful warm current in the Atlantic, moderates the climate of Western Europe, preventing it from experiencing the frigid winters found at similar latitudes in North America. Without this oceanic circulation, the distribution of life and the habitability of coastal regions would be drastically altered. You, in your daily life, are indirectly benefiting from this vast, invisible transport system.

Waves and Tides: The Ocean’s Breath

The rhythmic rise and fall of the tides, a spectacle that has captivated humanity for millennia, are governed by the gravitational pull of the Moon and the Sun. Tides are not just a curiosity for beachgoers; they play a vital role in coastal ecosystems, driving nutrient exchange and shaping intertidal zones, the dynamic border between land and sea. Waves, on the other hand, are primarily generated by wind. Their energy can sculpt coastlines, generating distinctive geological features, and they can also be harnessed as a renewable energy source, a testament to their immense power. Understanding wave dynamics is crucial for coastal engineering, maritime navigation, and predicting the impact of extreme weather events.

Thermodynamics and Mixing: The Ocean’s Internal Alchemy

The ocean’s temperature and salinity are not uniform. These variations, driven by solar heating, freshwater input, and evaporation, are fundamental to the ocean’s density. Denser, colder, saltier water tends to sink, while less dense, warmer, less salty water rises. This process of convection is a crucial driver of oceanic circulation, transporting heat from the equator towards the poles and influencing global weather patterns. Physical oceanographers use sophisticated models to understand these thermal and salinity gradients, and how they drive the mixing of ocean layers. This mixing is essential for distributing dissolved gases like oxygen and carbon dioxide, which are vital for marine life and play a critical role in regulating your atmosphere.

Chemical Oceanography: The Ocean’s Soluble Secrets

If physical oceanography examines the ocean’s movement, chemical oceanography scrutinizes its composition. It’s like examining the very blood of your planet, the dissolved substances that make life possible and shape the environment.

Dissolved Gases: The Ocean’s Lungs

The ocean is a massive reservoir of dissolved gases, including oxygen and carbon dioxide. Phytoplankton, the microscopic plants of the ocean, utilize carbon dioxide during photosynthesis, consuming it from the atmosphere and releasing oxygen. This process, known as the biological pump, is a cornerstone of Earth’s carbon cycle, profoundly influencing atmospheric CO2 concentrations and, consequently, your climate. Conversely, the ocean absorbs a significant portion of the carbon dioxide emitted by human activities, acting as a critical buffer against more rapid climate change. Chemical oceanographers meticulously measure these gas concentrations to understand the ocean’s role in regulating atmospheric composition and to assess the impacts of rising CO2 levels.

Nutrients and Fertilization: The Ocean’s Fertile Ground

The availability of essential nutrients, such as nitrates, phosphates, and silicates, dictates the productivity of marine ecosystems. These nutrients, often released from the seafloor or carried by rivers, act as fertilizers for phytoplankton blooms. Chemical oceanographers study the distribution and cycling of these nutrients, understanding how they fuel the food web that sustains countless marine species, from the smallest zooplankton to the largest whales. Changes in nutrient availability can have cascading effects throughout the ecosystem, impacting fisheries and the overall health of the marine environment.

Salinity and pH: The Ocean’s Chemical Balance

The salinity of seawater, approximately 35 parts per thousand on average, is a consequence of dissolved salts being carried into the oceans over geological timescales. Variations in salinity, influenced by evaporation, precipitation, and freshwater input from rivers, affect water density and therefore its circulation patterns. The pH of seawater, a measure of its acidity or alkalinity, is also crucial. The ocean is naturally slightly alkaline, but increasing atmospheric CO2 is leading to ocean acidification, a process that threatens marine organisms with calcium carbonate shells and skeletons, such as corals and shellfish. Chemical oceanographers are at the forefront of documenting and understanding these changes, highlighting the delicate chemical balance that underpins marine life.

Geological Oceanography: The Ocean Floor’s Story

The ocean floor is not a static, featureless plain. Geological oceanography is the discipline that reveals the dynamic processes shaping this vast underwater landscape, a history book written in rock and sediment.

Plate Tectonics Beneath the Waves: The Shifting Seafloor

Much of the Earth’s geological activity occurs beneath the oceans. Plate tectonics, the theory that describes the movement of the Earth’s lithospheric plates, is responsible for the formation of mid-ocean ridges, deep-sea trenches, and volcanic seamounts. These features are not mere curiosities; they are active geological zones that influence ocean currents, mediate heat exchange with the Earth’s interior, and are habitats for unique chemosynthetic ecosystems that thrive in the absence of sunlight. Studying submarine geology helps you understand the planet’s thermal budget and the long-term geological evolution of your world.

Sediment Transport and Deposition: The Ocean’s Memory

Sediments on the ocean floor are like layers of time, preserving a record of past environmental conditions. Geological oceanographers study marine sediments to reconstruct past climates, understand ocean circulation patterns, and trace the sources of pollutants. Sediment accumulation rates can vary widely, from the rapid deposition of organic matter in productive areas to the slow accumulation of fine clays in the abyss. The composition of these sediments – from a microscopic shell to a large pebble – tells a story about the ocean’s past, offering insights into events that transpired thousands or even millions of years ago.

Submarine Resources: The Ocean’s Treasures

The ocean floor contains vast reserves of mineral resources, including hydrocarbons (oil and natural gas), polymetallic nodules, and hydrothermal vent deposits, which are rich in metals like copper, gold, and silver. Geological oceanography plays a critical role in the exploration and responsible extraction of these resources. Understanding the geological formations and processes that concentrate these valuable materials is essential for sustainable resource management and for minimizing the environmental impact of extraction.

Biological Oceanography: The Ocean’s Vibrant Life

The ocean teems with life, from the microscopic to the colossal. Biological oceanography explores this incredible diversity, the intricate relationships between organisms, and their profound influence on marine ecosystems and beyond.

Plankton: The Foundation of the Marine Food Web

Phytoplankton, the drifting microscopic plants, are the primary producers of the ocean. Like tiny solar panels, they convert sunlight into energy, forming the base of the oceanic food web. Zooplankton, the drifting microscopic animals, graze on phytoplankton, and are in turn consumed by larger organisms. Together, plankton form the largest biomass on Earth and are critical for the ocean’s oxygen production and carbon sequestration. Biological oceanographers study plankton populations, their distribution, and their responses to environmental changes to understand the health of the entire marine ecosystem.

Marine Ecosystems: The Ocean’s Diverse Habitats

From the sunlit coral reefs, vibrant cities of the sea, to the crushing pressures of the abyssal plains, the ocean harbors an astonishing array of ecosystems. Biological oceanographers study the complex interactions within these environments, the predator-prey relationships, the symbiotic partnerships, and the competition for resources. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for conserving biodiversity, managing fisheries, and protecting vulnerable habitats from human impacts. Each ecosystem, a miniature world in itself, contributes to the overall functioning of the planet.

Marine Conservation: Protecting the Blue Heart

The health of marine ecosystems is intrinsically linked to your own well-being. Overfishing, pollution, habitat destruction, and climate change pose significant threats to marine life. Biological oceanographers are vital in providing the scientific basis for conservation efforts, identifying endangered species, assessing the effectiveness of marine protected areas, and advocating for sustainable practices. Their work helps you understand the consequences of your actions and guides you towards protecting this invaluable resource for future generations.

The Interconnectedness: How Oceanography Shapes Your World

The impacts of oceanography extend far beyond the study of marine life. Its findings are woven into the fabric of your daily existence, influencing everything from the air you breathe to the food you eat and the weather you experience.

Climate Regulation: The Ocean’s Thermostat

You often think of weather as something that happens in the atmosphere. However, the ocean acts as a colossal thermostat, absorbing and releasing vast amounts of heat, thereby moderating global temperatures. Ocean currents, as you’ve learned, are instrumental in this heat redistribution. Changes in ocean temperature can lead to shifts in weather patterns, influencing the frequency and intensity of extreme events like hurricanes and droughts. Oceanography provides the critical data and models to understand these complex climate feedbacks, allowing you to better predict and prepare for the impacts of a changing climate.

Food Security: From Sea to Table

Billions of people worldwide rely on the ocean as a primary source of protein. Fisheries, the industries that harvest marine life, provide employment and sustenance for coastal communities and beyond. Biological and chemical oceanography are indispensable for sustainable fisheries management. Understanding fish populations, their reproductive cycles, and the health of their habitats allows for the setting of fishing quotas and the implementation of practices that prevent overexploitation. Without this scientific guidance, the bounty of the ocean could be depleted, leading to food insecurity and economic hardship.

Resource Management: The Ocean’s Hidden Wealth

Beyond food, the ocean floor holds reserves of valuable resources, from minerals to potential pharmaceutical compounds. Geological and chemical oceanography are essential for the sustainable exploration and extraction of these resources. Developing strategies that minimize environmental disruption and ensure equitable access to these resources is a complex challenge that requires a deep understanding of marine geology and chemistry.

Navigation and Commerce: The Ocean’s Highways

For centuries, the ocean has served as the primary highway for global commerce. Accurate charting of ocean depths, understanding of currents and tides, and the study of weather patterns are all products of oceanographic research. These advancements are crucial for the safe and efficient transport of goods, supporting the interconnected global economy that you are a part of. From the ships that carry your electronics to the submarines that explore the depths, oceanography underpins your maritime activities.

The Future of Exploration: New Frontiers and Challenges

The journey of oceanographic exploration is far from over. As technology advances, new frontiers are opening up, and existing challenges demand greater attention.

Technological Advancements: Deeper, Wider, Smarter Exploration

Your ability to explore the ocean is rapidly evolving. New generations of autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) and remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) are capable of venturing into the deepest, most inaccessible parts of the ocean, collecting data with unprecedented precision. Satellite oceanography provides a global perspective, monitoring sea surface temperatures, currents, and sea-level rise. Advances in genetic sequencing and bio-imaging are revealing the intricate details of marine life and the complex ecological interactions that govern its existence. As these technologies become more sophisticated, your understanding of the ocean will expand exponentially.

The Urgency of Climate Change: An Ocean Under Stress

The impacts of climate change are profoundly felt in the ocean. Rising sea levels threaten coastal communities, ocean acidification endangers marine life, and warming waters disrupt ecosystems. Oceanographers are on the front lines of documenting these changes, predicting their future trajectory, and developing strategies for mitigation and adaptation. The ocean is not just a victim of climate change; it is also a crucial part of the solution, and understanding its role in the Earth’s climate system is paramount.

Unveiling the Unknown: The Abyssal Frontier

Despite your technological progress, a vast majority of the ocean remains unexplored. The deep sea, with its extreme pressures, perpetual darkness, and unique life forms, holds secrets that could revolutionize our understanding of biology, chemistry, and geology. Further exploration of these abyssal plains, hydrothermal vents, and hadal zones promises to reveal novel organisms, new chemical processes, and insights into the early history of life on Earth.

In conclusion, oceanography is not a niche scientific field for a select few. It is a vital discipline that provides you with the knowledge necessary to understand and interact with the largest and most influential component of your planet. By continuing to explore the depths, you are, in essence, exploring yourself and securing the future of the world you inhabit. The ocean is a silent, powerful force, and your understanding of it is a testament to your curiosity and your capacity for stewardship.

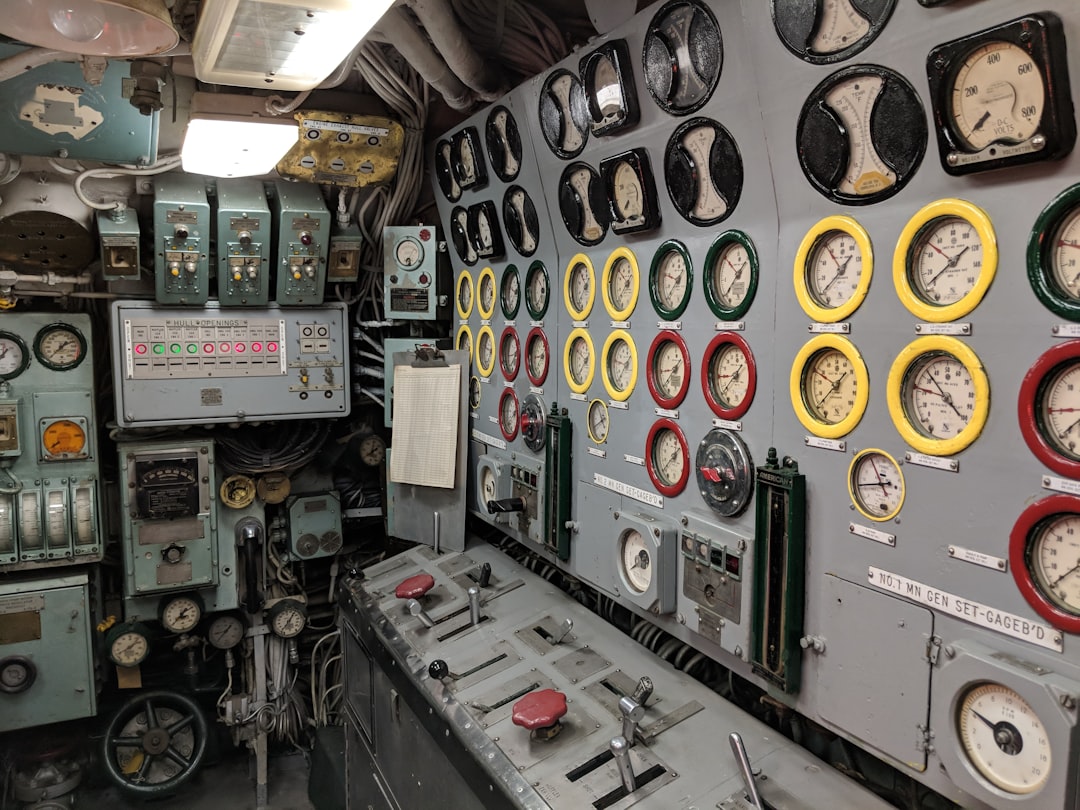

WATCH NOW▶️ Submarine detection technology history

FAQs

What is oceanography?

Oceanography is the scientific study of the ocean, including its physical, chemical, biological, and geological aspects. It involves understanding ocean currents, marine ecosystems, ocean floor geology, and the interactions between the ocean and the atmosphere.

What are the main branches of oceanography?

The main branches of oceanography are physical oceanography (studying ocean currents, waves, and tides), chemical oceanography (examining the chemical composition of seawater), biological oceanography (studying marine organisms and ecosystems), and geological oceanography (exploring the structure and history of the ocean floor).

Why is oceanography important?

Oceanography is important because it helps us understand climate regulation, marine biodiversity, natural resources, and environmental changes. It also supports navigation, fisheries management, and disaster prediction such as tsunamis and hurricanes.

How do oceanographers collect data?

Oceanographers collect data using various tools such as research vessels, satellites, underwater robots (ROVs and AUVs), buoys, and sensors. They measure parameters like temperature, salinity, currents, and marine life to study ocean conditions and processes.

What role does oceanography play in climate science?

Oceanography plays a crucial role in climate science by studying how oceans absorb and store heat and carbon dioxide, influencing global climate patterns. Understanding ocean circulation and interactions with the atmosphere helps predict climate change impacts and extreme weather events.