Sonar technology, an acronym for Sound Navigation and Ranging, has been a cornerstone of naval operations since its widespread adoption in the early 20th century. Its fundamental principle, the propagation of sound waves to detect and locate underwater objects, has evolved profoundly, transitioning from rudimentary echo-sounding to sophisticated multi-static, high-frequency systems. This article explores the multifaceted ways in which sonar enhances military operations, examining its applications across various domains, the technological strides that have broadened its capabilities, and the inherent challenges that continue to shape its development.

At its core, sonar provides the military with a pair of highly sensitive ears in the ocean’s opaque depths. Unlike electromagnetic waves, which are severely attenuated by water, sound travels efficiently, making it the primary medium for underwater communication, detection, and navigation.

Active vs. Passive Sonar Systems

The operational spectrum of sonar is broadly categorized into active and passive systems, each with distinct advantages and applications.

Active Sonar: Emitting and Listening

Active sonar operates by emitting acoustic pulses, often termed “pings,” and then listening for the echoes that rebound from submerged objects. The time taken for the echo to return, coupled with the known speed of sound in water, allows for the calculation of an object’s range. The direction from which the echo originates provides bearing information.

- Target Detection and Ranging: This is the most straightforward application, enabling the localization of submarines, mines, and even surface vessels if submerged components are within range.

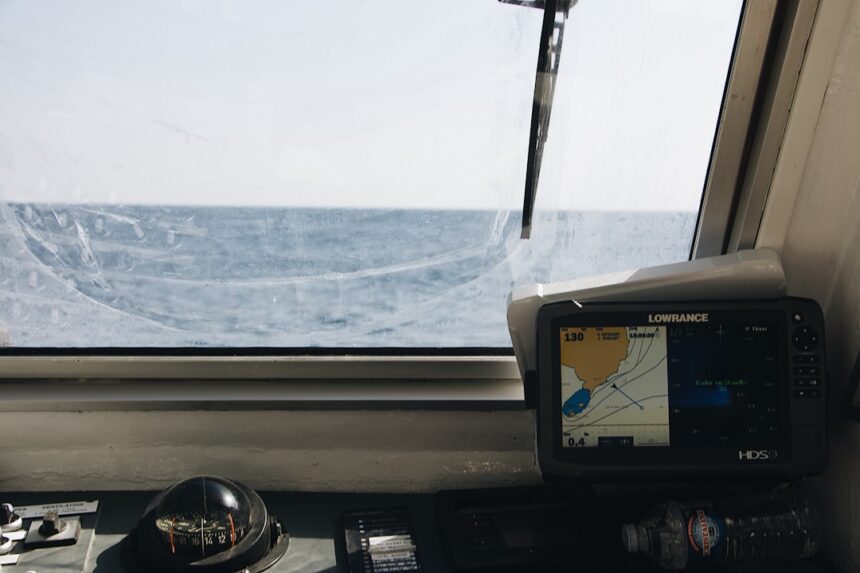

- Underwater Mapping and Navigation: Active sonar, particularly multi-beam variants, can create detailed topographic maps of the seafloor, crucial for safe navigation, laying underwater infrastructure, and planning amphibious assaults.

- Mine Countermeasures (MCM): High-frequency active sonar is indispensable in MCM operations, providing the resolution necessary to identify and classify even small, irregularly shaped objects on or near the seabed as potential mines.

Passive Sonar: The Art of Listening

Passive sonar, in contrast, does not transmit sound. Instead, it silently listens for acoustic emissions generated by other vessels or underwater phenomena. This stealthy approach offers significant tactical advantages, as it does not betray the listener’s presence.

- Submarine Detection and Tracking: Submarines, by their very nature, strive for acoustic stealth. However, even the quietest submarines generate noise from propellers, machinery, and flow noise. Passive sonar arrays are designed to detect and characterize these faint signatures.

- Ocean Surveillance: Large, distributed passive sonar arrays, such as the once-classified SOSUS (Sound Surveillance System), were deployed to monitor vast oceanic areas for submarine activity. These systems exemplify the broad reach of passive listening.

- Acoustic Signature Analysis: The unique acoustic fingerprint of a vessel can be analyzed to determine its type, class, and even specific characteristics, providing invaluable intelligence.

Sonar technology has become increasingly vital in military operations, particularly in underwater warfare and surveillance. A related article that delves into the advancements and applications of sonar in modern military strategies can be found at In the War Room. This article explores how sonar systems enhance naval capabilities, improve threat detection, and contribute to strategic planning in maritime environments.

Expanding the Operational Horizon

Modern sonar technology has transcended the basic “ping and listen” paradigm, integrating advanced signal processing, artificial intelligence, and network-centric capabilities to enhance its utility across a wider range of military operations.

Anti-Submarine Warfare (ASW) Enhancement

ASW remains a primary domain where sonar continues to evolve, as the proliferation of advanced, quiet submarines necessitates increasingly sophisticated detection and tracking capabilities.

Towed Array Sonar (TAS)

Towed array sonar systems, comprising long, flexible cables equipped with numerous hydrophones, are trailed behind surface ships and submarines. These arrays extend the acoustic baseline significantly, improving detection range and bearing accuracy for subtle contacts.

- Increased Detection Range: By operating away from the towing platform’s own noise, TAS can achieve much greater detection ranges, acting as an elongated ear in the water.

- Improved Bearing Resolution: The length of the array provides a broader aperture, enabling more precise localization of submerged contacts, aiding in tracking and targeting.

- Variability in Depth: TAS can be deployed at different depths, allowing for optimal acoustic performance in varying oceanographic conditions and the exploitation of sound propagation channels.

Sonobuoys and Distributed Acoustic Sensing

Sonobuoys are expendable sonar devices deployed from aircraft, surface ships, or submarines. They represent a flexible, temporary, and geographically dispersed sonar network.

- Aircraft-Deployed ASW: Maritime patrol aircraft (MPA) drop patterns of sonobuoys, creating an acoustic net to locate, track, and reacquire submarines in broad areas.

- Passive and Active Variants: Sonobuoys come in both passive (listening-only) and active (transmitting and receiving) configurations, offering tactical flexibility.

- Networked Sonar Fields: Multiple sonobuoys can be linked to form a distributed acoustic sensing field, allowing for triangulation and enhanced tracking of stealthy sub-surface contacts.

Mine Countermeasures (MCM) and Underwater Unexploded Ordnance (UXO)

The threat posed by naval mines and legacy UXO in coastal waters and shipping lanes necessitates advanced sonar solutions for safe navigation and operational freedom.

Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs) with Sonar

AUVs equipped with high-resolution sonar systems are increasingly employed for MCM missions. These unmanned platforms can systematically survey vast areas without putting human operators at risk.

- High-Resolution Side-Scan Sonar: This technology produces detailed imagery of the seabed, making it possible to identify mine-like objects based on their shape and acoustic shadow.

- Synthetic Aperture Sonar (SAS): SAS techniques synthesize a larger effective aperture from multiple pings, achieving significantly higher resolution imagery than conventional side-scan sonar, even revealing fine details of mine features.

- Reduced Human Risk: AUVs eliminate the need for divers or manned vessels to operate directly in potentially mined areas, enhancing safety.

Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs) for Identification and Neutralization

Once potential mine-like objects are detected by survey sonars, ROVs are deployed to visually identify and, if necessary, neutralize the threat.

- Integrated Sonar and Cameras: ROVs often carry small, high-frequency sonars for precise localization in low-visibility water, complementing optical cameras for detailed inspection.

- Manipulator Arms: Equipped with manipulator arms, some ROVs can attach neutralization charges or retrieve objects for forensic analysis, further reducing human exposure to risk.

Enhancing Naval Force Protection

Sonar’s role extends beyond hunting submarines and mines; it is a vital component in protecting surface vessels and critical infrastructure from a range of underwater threats.

Port and Harbor Security

The vulnerability of ports and harbors to underwater threats, such as saboteurs with limpet mines or small unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs), has led to the deployment of specialized sonar systems.

Diver Detection Sonar (DDS)

DDS systems are typically fixed multi-beam sonars deployed around vital assets or harbor entrances. They are optimized to detect the small acoustic signature of human swimmers or small UUVs.

- Early Warning for Intrusion: DDS provides an early warning capability against underwater incursions, allowing security forces to intercept threats before they reach their targets.

- High-Frequency Operation: These sonars often operate at higher frequencies to achieve the necessary resolution for distinguishing small targets from environmental clutter.

- Automated Alarms: Advanced DDS systems employ sophisticated algorithms to automatically detect and classify potential threats, minimizing false alarms.

Anti-Saboteur Measures

Sonar-equipped UUVs or remotely operated surface vehicles (ROSVs) can be deployed as mobile patrols to augment fixed DDS systems, offering flexible area coverage.

- Mobile Surveillance: ROSVs carrying compact sonars can patrol designated areas, providing dynamic protection and responding to alerts from fixed sensors.

- Integration with Other Sensors: Sonar data can be fused with radar, electro-optical/infrared (EO/IR) systems, and other sensors to create a comprehensive security picture.

The Challenges of the Underwater Domain

Despite its sophistication, sonar operation is not without significant challenges, dictated by the relentless variability of the underwater environment. This domain is a complex, ever-shifting canvas, impacting sound propagation in profound ways.

Environmental Factors Affecting Sound Propagation

The ocean is not a uniform medium; its acoustic properties are dramatically influenced by a host of environmental variables.

Temperature and Salinity Gradients

Variations in water temperature and salinity create density layers that refract and scatter sound waves, much like light rays passing through different media.

- Sound Channels: Under specific conditions, temperature and pressure profiles can create “sound channels” (e.g., the SOFAR channel) that allow sound to travel thousands of kilometers with minimal attenuation. Conversely, these channels can also create “shadow zones” where sound cannot penetrate.

- Thermal Layers (Thermoclines): Sharp temperature changes, particularly thermoclines, can act as acoustic mirrors, reflecting sound waves and making detection difficult across these boundaries. This can significantly reduce sonar range and create opportunities for submarines to hide.

Marine Life and Bottom Topography

Biological noise and the physical characteristics of the seafloor contribute significantly to the acoustic environment.

- Biological Noise: Whales, dolphins, shrimp, and other marine life produce a cacophony of sounds that can mask target signatures or generate false contacts, demanding advanced signal processing to filter out irrelevant signals.

- Bottom Clutter and Reverberation: Uneven seabed topography, rocks, and sediment cause sound waves to scatter and reflect, creating “bottom reverberation” that can obscure targets, especially in shallow water environments. This phenomenon necessitates careful sonar design and operational tactics.

Evolving Countermeasures and Stealth Technologies

Adversaries are continually developing methods to counter sonar’s effectiveness, driving a perpetual innovation cycle in military acoustics.

Acoustic Stealth and Anechoic Coatings

Modern submarines and UUVs are designed with sophisticated acoustic stealth features to minimize their radiated noise and absorb incident sonar pulses.

- Quieter Propulsion Systems: Electric drives and advanced propeller designs reduce mechanical noise, making detection by passive sonar extremely challenging.

- Anechoic Tiles and Coatings: These specialized materials are applied to the hull to absorb sonar pings, significantly reducing the strength of the returning echo, thereby shortening active sonar’s detection range.

Jamming and Decoys

Electronic warfare (EW) techniques can be used against active sonar, while acoustic decoys can confuse both active and passive systems.

- Sonar Jammers: These devices emit powerful acoustic signals designed to overwhelm the receiving hydrophones of an active sonar, making it difficult to detect legitimate echoes.

- Acoustic Decoys: Self-propelled or static decoys can mimic the acoustic signature of a high-value target, diverting torpedoes or confusing an attacker’s sonar tracking. These can be particularly effective in creating false contacts and increasing the processing burden on an adversary.

Sonar technology plays a crucial role in modern military operations, enhancing underwater surveillance and navigation capabilities. For a deeper understanding of its applications and advancements, you can explore a related article that discusses the integration of sonar systems in naval warfare. This resource provides valuable insights into how sonar technology is evolving to meet the demands of contemporary military challenges. To read more about this topic, visit this article.

The Future Trajectory of Sonar Technology

| Metric | Description | Typical Value / Range | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency Range | Operating frequency of military sonar systems | 1 – 100 | kHz |

| Detection Range | Maximum distance at which targets can be detected | 1 – 50 | km |

| Resolution | Ability to distinguish between two close objects | 0.1 – 10 | meters |

| Source Level | Sound intensity emitted by the sonar source | 200 – 235 | dB re 1 μPa @ 1m |

| Pulse Length | Duration of the sonar pulse | 0.1 – 100 | milliseconds |

| Beamwidth | Angular width of the sonar beam | 1 – 30 | degrees |

| Operating Depth | Depth range for sonar operation | 0 – 6000 | meters |

| Signal Processing Delay | Time taken to process sonar signals | 10 – 500 | milliseconds |

The trajectory of sonar technology points towards increased integration, autonomy, and intelligence, aiming to overcome the inherent challenges of the underwater domain.

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

AI and ML are poised to revolutionize sonar data analysis, enhancing detection, classification, and tracking capabilities.

Automated Target Recognition (ATR)

ATR algorithms, trained on vast datasets of acoustic signatures, will enable sonars to automatically identify and classify underwater objects with greater accuracy and speed than human operators.

- Reduced Operator Workload: AI can sift through torrents of sonar data, highlighting potential contacts and reducing the cognitive burden on human analysts, allowing them to focus on complex scenarios.

- Improved Classification Accuracy: ML models can discern subtle patterns in acoustic data that might be imperceptible to human ears, leading to more reliable identification of stealthy targets.

Predictive Analytics for Environmental Factors

AI models can leverage real-time oceanographic data (temperature, salinity, currents, seabed composition) to predict sound propagation conditions, optimizing sonar settings and tactical deployments.

- Adaptive Sonar Beamforming: AI can dynamically adjust sonar beam patterns and frequencies to exploit optimal acoustic paths and mitigate the effects of adverse environmental conditions.

- Optimized Search Patterns: By predicting areas of good and poor sound propagation, AI can recommend search patterns that maximize the probability of detection while minimizing exposure to risk.

Integrated and Networked Sonar Systems

The future involves highly integrated sensor networks where sonar data is seamlessly shared and fused with information from other sensor types (e.g., magnetic anomaly detectors, non-acoustic sensors).

Multi-Static and Bi-Static Sonar Networks

These advanced configurations employ geographically separated transmitters and receivers, enhancing detection capabilities against stealthy targets.

- Overcoming Stealth: By pinging from one location and listening from multiple others, multi-static sonar can exploit the weak acoustic returns from stealthy platforms that might be missed by a single monostatic (transmitter and receiver co-located) system.

- Improved Localization: The geometric diversity offered by multiple receive platforms provides superior localization capabilities, pinning down the position of even faint contacts.

Collaborative Autonomous Systems

Swarms of networked UUVs equipped with compact sonars could form highly adaptable and resilient underwater surveillance grids, operating autonomously for extended periods.

- Persistent Surveillance: Autonomous sonar networks can maintain continuous watch over critical areas, responding dynamically to detected threats or changes in environmental conditions.

- Distributed Sensing and Processing: The collective intelligence of a UUV swarm can fuse data from individual platforms to build a comprehensive picture of the underwater environment, surpassing the capabilities of any single platform.

In conclusion, sonar technology, a sentinel of the deep, continues its journey from rudimentary echo-sounding to complex, intelligent networks. Its evolution is a testament to the persistent demand for oceanic situational awareness in military operations. Facing the immutable laws of fluid dynamics and the ingenuity of adversaries, sonar remains at the forefront, adapting, innovating, and projecting its acoustic gaze into the ocean’s vast and often enigmatic realms. Its continued enhancement is not merely an incremental improvement but a fundamental driver of maritime security and strategic advantage. The silent war beneath the waves is one where the keenest ears often hold the greatest sway.

FAQs

What is sonar technology and how is it used in the military?

Sonar technology uses sound waves to detect, locate, and identify objects underwater. In the military, it is primarily used for submarine detection, navigation, mine detection, and underwater communication.

What are the two main types of sonar used in military applications?

The two main types of sonar are active sonar, which emits sound pulses and listens for echoes, and passive sonar, which listens for sounds made by other vessels without emitting any signals.

How does sonar help in submarine warfare?

Sonar helps detect enemy submarines by sending sound waves through water and analyzing the echoes that bounce back. This allows military forces to track submarine movements, avoid threats, and engage targets effectively.

What are the limitations of sonar technology in military use?

Limitations include reduced effectiveness in noisy or cluttered underwater environments, limited range depending on water conditions, and the risk of revealing one’s own position when using active sonar.

How has sonar technology evolved in modern military systems?

Modern sonar systems have improved sensitivity, range, and signal processing capabilities. Advances include digital signal processing, integration with other sensors, and the development of low-frequency sonar for long-range detection.