The ocean depths, a realm long shrouded in mystery, are undergoing a critical examination as humanity grapples with dwindling terrestrial resources and the inexorable march of technological advancement. One name that resonates with both historical intrigue and contemporary relevance in this discourse is the Glomar Explorer. This vessel, a titan of engineering forged in the fires of Cold War espionage, inadvertently became a harbinger of the future, illuminating both the immense technical challenges and the profound ethical quandaries associated with exploiting the last frontier on Earth: the deep seabed.

The Glomar Explorer, a marvel of naval architecture, was not initially conceived as an instrument of resource extraction. Its origins are firmly rooted in the clandestine operations of the Cold War, a period defined by a tense geopolitical standoff between superpowers.

Project Azorian: A Covert Endeavor

The genesis of the Glomar Explorer lies within ‘Project Azorian,’ a highly classified operation orchestrated by the United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). The primary objective of this audacious project was the recovery of a Soviet Golf II-class submarine, the K-129, which had mysteriously sunk in 1968 approximately 1,600 nautical miles northwest of Hawaii. The K-129 carried nuclear missiles and classified cryptographic materials, making its retrieval a strategic imperative for the States.

- Engineering an Illusion: To mask the true purpose of the vessel, the CIA, in collaboration with Howard Hughes’ Summa Corporation, propagated the elaborate cover story that the Glomar Explorer was designed for deep-sea manganese nodule mining. This narrative served as a perfect smokescreen, lending credibility to the immense scale and specialized equipment of the ship.

- Technological Prowess: The Glomar Explorer was a groundbreaking feat of engineering. It featured a massive internal “moon pool,” a hinged derrick, and a colossal claw-like grappling device known as the “capture vehicle” or “Clementine.” These components were designed to painstakingly lift large sections of the sunken submarine from depths exceeding 16,000 feet (4,900 meters). The precision required for such an operation, in an environment of extreme pressure and perpetual darkness, was unprecedented.

Partial Success and Public Disclosure

Despite its sophisticated design and meticulous planning, Project Azorian was only partially successful. While the Glomar Explorer did manage to recover a significant portion of the K-129, including some crucial intelligence, a structural failure in the capture vehicle resulted in a large segment of the submarine breaking apart and falling back to the seabed.

- The Unveiling: The secrecy surrounding Project Azorian was eventually shattered by a series of leaks and investigative journalism. In 1975, the Los Angeles Times publicly exposed the true nature of the Glomar Explorer’s mission, triggering a media sensation and a diplomatic incident with the Soviet Union.

- A New Era of Transparency (and Cover-ups): The Glomar Explorer incident, while revealing a fascinating chapter of Cold War intrigue, also forced a re-evaluation of government secrecy and the public’s right to information. It illustrated the lengths to which states would go to gain an advantage, even under the guise of commercial enterprise.

The Glomar Explorer, a vessel originally designed for deep-sea mining, has played a significant role in the evolution of underwater resource extraction. For those interested in exploring the broader implications of deep-sea mining and its impact on the environment and economy, a related article can be found at In the War Room. This article delves into the challenges and advancements in the industry, highlighting the ongoing debates surrounding sustainability and technological innovation in deep-sea exploration.

Deep-Sea Mining: The Allure of Abundance

The cover story for the Glomar Explorer, far from being a mere fabrication, inadvertently highlighted a genuine and growing interest: the potential for deep-sea mining. As terrestrial reserves of critical minerals dwindle and global demand escalates, the deep seabed beckons as a vast, untapped repository of essential resources.

The Riches Beneath: Types of Deep-Sea Mineral Deposits

The abyssal plains, hydrothermal vents, and seamounts of the ocean floor are home to three primary types of mineral deposits that are of significant commercial interest.

- Polymetallic Nodules: These potato-sized concretions, found predominantly on the abyssal plains at depths of 4,000 to 6,000 meters, are rich in manganese, nickel, copper, and cobalt. These minerals are vital components in batteries, electronics, and renewable energy technologies.

- Polymetallic Sulphides: Located near active and inactive hydrothermal vents, often referred to as “black smokers,” these deposits are rich in copper, zinc, gold, and silver. Their formation is intrinsically linked to the volcanic activity of mid-ocean ridges.

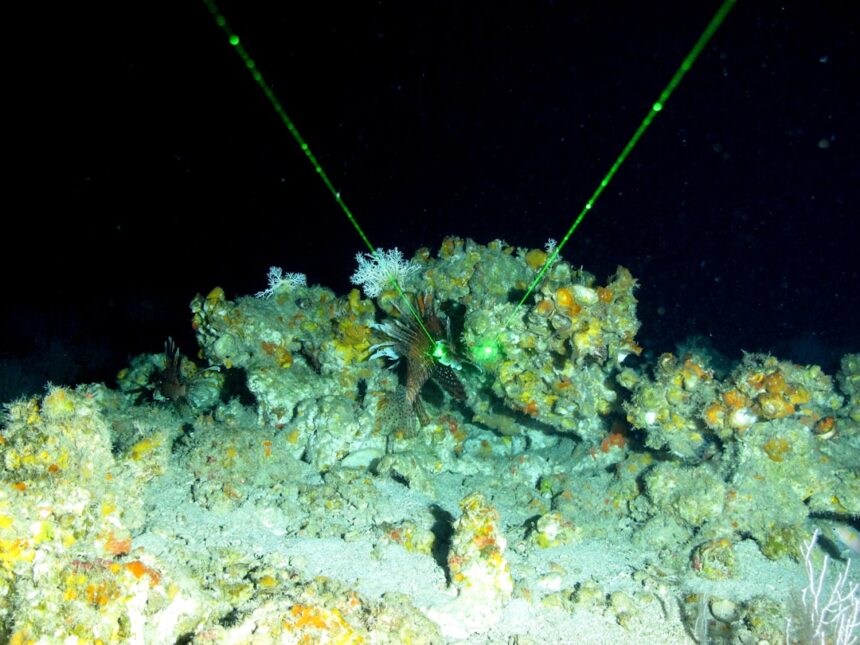

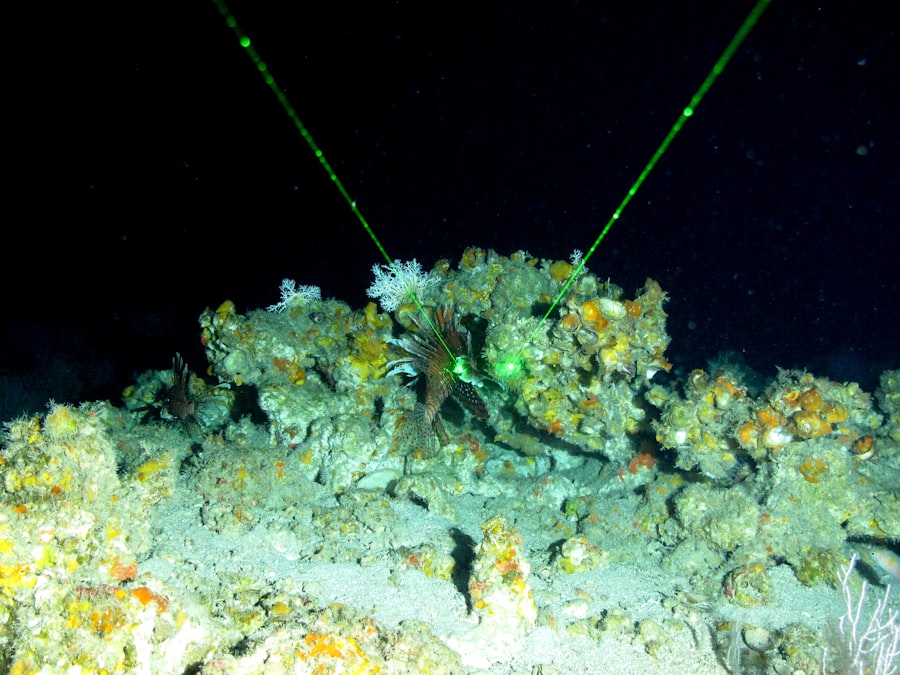

- Cobalt-Rich Ferromanganese Crusts: These dense layers of minerals accrete on the flanks of seamounts and other hard-rock substrates at depths ranging from 800 to 2,500 meters. They are particularly abundant in cobalt, nickel, tellurium, and platinum group metals, crucial for high-tech applications.

The Economic Imperative: Why Go Deeper?

The motivation for deep-sea mining is multifaceted, driven by a confluence of economic, geopolitical, and technological factors.

- Resource Scarcity and Demand: The global demand for critical minerals, particularly those used in electric vehicles, wind turbines, and advanced electronics, is projected to surge in the coming decades. Terrestrial mining faces increasing challenges, including declining ore grades, environmental regulations, and political instability in resource-rich regions.

- Technological Advancements: The very technology that enabled the Glomar Explorer’s Cold War mission – remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), and advanced sensing systems – has matured considerably. These advancements make the prospect of deep-sea mining, once a futuristic dream, an increasingly tangible reality.

- Geopolitical Considerations: Access to critical minerals is becoming a strategic imperative for nations. Diversifying supply chains away from a few dominant terrestrial producers and securing independent access to resources offers a degree of geopolitical stability and economic resilience.

The Glomar Explorer’s Legacy: A Blueprint for the Future?

While the Glomar Explorer’s primary mission was espionage, its design and operational capabilities provide valuable insights into the technical challenges and potential solutions for deep-sea mining operations.

Engineering Echoes: From Spy Ship to Mineral Harvester

The fundamental principles of deep-sea retrieval employed by the Glomar Explorer – precise positioning, heavy lifting in extreme depths, and remote operation – are directly transferable to the realm of mineral extraction.

- Moon Pool Technology: The Glomar Explorer’s moon pool, a vertical shaft extending through the hull, allowed for the deployment and retrieval of large equipment in a sheltered environment, mitigating the effects of surface waves. This design has since become a standard feature in many offshore drilling and research vessels, and its adaptation for deploying mining vehicles and risers is a natural progression.

- Dynamic Positioning Systems: The ability to maintain a precise position over a target area, even in challenging ocean currents, was paramount for Project Azorian. Modern dynamic positioning (DP) systems, utilizing computer-controlled thrusters and GPS, are essential for deep-sea mining platforms to accurately traverse concession areas and prevent damage to delicate equipment.

- Remote Operations and Automation: The vast distances and inhospitable nature of the deep sea necessitate highly automated and remotely operated systems. The Glomar Explorer’s reliance on remote control for its grappling mechanisms foreshadowed the current reliance on ROVs and AUVs for surveying, sample collection, and eventually, mineral extraction.

Beyond the Hardware: Operational Lessons

The operational experience gained from Project Azorian, despite its secrecy, offered invaluable lessons in managing complex, high-risk deep-sea endeavors.

- Logistical Challenges: Mobilizing and sustaining a deep-sea operation of the Glomar Explorer’s magnitude required meticulous planning and extensive logistical support. For future deep-sea mining, the logistics of transporting vast quantities of ore from remote ocean depths to processing facilities will be a colossal undertaking.

- Risk Mitigation: The partial failure of the capture vehicle highlighted the inherent risks and unforgiving nature of the deep-sea environment. Future mining operations will need robust risk assessment frameworks and contingency plans to address equipment failures, environmental incidents, and other unforeseen complications.

- The Unpredictable Deep: The deep sea remains a largely unknown frontier, a “blank slate” in many respects. The challenges encountered by the Glomar Explorer underscored the need for thorough environmental baseline studies and a deep understanding of the unique geological and biological characteristics of potential mining sites.

Environmental Implications: A Double-Edged Sword

While deep-sea mining offers the promise of vital resources, it also presents a formidable array of environmental concerns. The pristine and often unique ecosystems of the deep sea are particularly vulnerable to anthropogenic disturbance.

The Fragile Abyss: Unique Ecosystems at Risk

The deep seabed, once thought to be a barren wasteland, is now recognized as home to an astonishing diversity of life, much of which is endemic and highly specialized.

- Hydrothermal Vents: These oases of life, fueled by chemosynthesis rather than photosynthesis, support unique communities of bacteria, tube worms, crabs, and other invertebrates. Mining polymetallic sulphides near these vents could irrevocably alter these ecosystems.

- Abyssal Plains and Seamounts: Even the seemingly uniform abyssal plains harbor a wealth of biodiversity, including sponges, corals, and unique benthic organisms. Seamounts, acting as underwater islands, often host highly concentrated and endemic species, making them biodiversity hotspots.

- Slow Recovery Rates: Deep-sea ecosystems are characterized by slow growth rates, long lifespans, and low reproductive rates. Disturbances, such as those caused by mining, can take centuries or even millennia to recover, if at all.

Direct and Indirect Impacts of Mining

The process of deep-sea mining, from exploration to extraction and processing, carries a spectrum of potential environmental harms.

- Habitat Destruction: The physical removal of mineral deposits will directly destroy the habitats of benthic organisms. Collectors, resembling giant vacuum cleaners or plows, will scrape or dredge the seabed, indiscriminately removing or smothering marine life.

- Sediment Plumes: The mining process will inevitably generate vast plumes of sediment. These plumes can spread over large areas, smothering organisms, reducing light penetration, and potentially altering water chemistry. The long-term effects of these plumes on filter feeders, larval dispersal, and nutrient cycling are poorly understood.

- Noise and Light Pollution: The constant operation of mining machinery, along with the bright lights of ROVs and collectors, could disrupt the sensitive behaviors of deep-sea fauna, many of which rely on chemosensory cues and thrive in perpetual darkness.

- Toxic Discharge: The dewatering process on the surface vessel, designed to separate minerals from sediment, could lead to the discharge of sediment-laden wastewater, potentially containing heavy metals, into the water column, impacting pelagic ecosystems.

The Glomar Explorer, a vessel famously associated with deep sea mining, has sparked significant interest in the potential of underwater resource extraction. As the industry evolves, many are looking to understand the implications of such ventures on the environment and global economies. For a deeper dive into the complexities surrounding deep sea mining, you can read a related article that explores these themes in detail. This article provides insights into the challenges and opportunities presented by this emerging field, making it a valuable resource for anyone interested in the future of oceanic exploration. For more information, visit this article.

Governance and Regulation: Navigating the Legal Labyrinth

| Metric | Value | Unit | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year of Launch | 1974 | Year | Glomar Explorer was originally built for Project Azorian |

| Vessel Length | 185 | meters | Length of the Glomar Explorer ship |

| Gross Tonnage | 18,000 | tons | Approximate gross tonnage of the vessel |

| Mining Depth Capability | 6,000 | meters | Maximum operational depth for deep sea mining |

| Primary Minerals Targeted | Cobalt, Manganese, Nickel | — | Common metals sought in deep sea mining |

| Mining Method | Hydraulic Suction and Mechanical Excavation | — | Techniques used in deep sea mining operations |

| Environmental Impact Concerns | High | Qualitative | Concerns about seabed disturbance and ecosystem damage |

| Operational Status | Decommissioned | — | Glomar Explorer is no longer active in mining |

The deep seabed lies largely beyond national jurisdiction, falling under the purview of international law. This presents a complex web of governance challenges for deep-sea mining, a critical aspect that was never considered during the Glomar Explorer’s clandestine operations.

The Role of the International Seabed Authority (ISA)

The International Seabed Authority (ISA), established under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), is tasked with organizing and controlling mineral-related activities in the international seabed area, known as “the Area.”

- Dual Mandate: The ISA has a unique dual mandate: to facilitate the development of deep-sea mineral resources for the benefit of all humankind and to ensure the effective protection of the marine environment from harmful effects of mining activities. Balancing these two objectives is a constant challenge.

- Developing Regulations: The ISA is currently in the process of finalizing a comprehensive set of regulations for deep-sea mining, often referred to as the “Mining Code.” This code will cover prospecting, exploration, and exploitation activities, including environmental management plans, financial arrangements, and reporting requirements.

- Stakeholder Consultations: The ISA’s work involves extensive consultations with member states, scientific experts, environmental organizations, and industry representatives, reflecting the diverse and often conflicting interests at play.

Challenges and Controversies in Governance

Even with the ISA’s framework, numerous challenges and controversies persist, mirroring the ethical dilemmas inherent in exploiting a shared global commons.

- The “Common Heritage of Mankind” Principle: UNCLOS declares the deep seabed and its resources as the “common heritage of mankind,” implying that benefits from deep-sea mining should be equitably shared among all nations. Defining and implementing this principle, particularly concerning financial mechanisms and technology transfer, remains a significant hurdle.

- Precautionary Principle and Environmental Baselines: Many environmental organizations advocate for a moratorium on deep-sea mining, citing the lack of sufficient scientific data, particularly concerning environmental baselines and the long-term impacts of mining. They argue that the “precautionary principle” should be applied, meaning that measures should be taken to prevent harm even if full scientific certainty is lacking.

- Transparency and Accountability: Concerns are often raised regarding the transparency of the ISA’s decision-making processes and the potential for regulatory capture by industry interests. Ensuring robust independent oversight and effective enforcement mechanisms will be crucial for public trust and environmental protection.

- Technological Readiness and Regulatory Lag: The pace of technological development for deep-sea mining is often outstripping the development of comprehensive regulations. This regulatory lag creates uncertainty for both industry and environmental stakeholders.

Addressing the Future: Balancing Progress and Preservation

The Glomar Explorer, a relic of a bygone era, casts a long shadow over the future of deep-sea mining. Its story serves as a potent reminder of humanity’s capacity for technological ingenuity, but also of the profound ethical responsibilities that accompany such power. The path forward demands a delicate balance, much like a tightrope walker navigating a chasm.

Sustainable Strategies and Alternative Solutions

To truly progress, the conversation must expand beyond simply whether to mine, to how mining, if it proceeds, can be conducted sustainably, and what alternatives exist.

- Circular Economy Principles: Embracing a circular economy model, where resources are reused, recycled, and repurposed, can significantly reduce the demand for virgin materials, including those from the deep sea. This involves designing products for longevity, facilitating repair, and investing in efficient recycling technologies.

- Urban Mining: Recovering valuable minerals from discarded electronic waste, often referred to as “urban mining,” presents a significant opportunity. The concentration of precious metals in e-waste often surpasses that of natural ores, making it a potentially lucrative and environmentally sound alternative.

- Technological Innovation Towards Efficiency: Continued innovation in material science could lead to the development of substitute materials that require fewer critical minerals or advanced manufacturing processes that use resources more efficiently.

- Rigorous Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs): Before any deep-sea mining operation commences, comprehensive and independent EIAs are paramount. These assessments must establish robust environmental baselines, predict potential impacts, and develop effective mitigation and monitoring strategies.

A Call for Global Collaboration

The challenges and opportunities presented by deep-sea mining transcend national borders. The deep sea is a shared global commons, and its future requires concerted international effort.

- Scientific Research: Continued investment in deep-sea scientific research is fundamental. We must expand our understanding of deep-sea ecosystems, their resilience, and their interconnectedness to better inform policy and mitigate risks. This requires collaborative international research programs and open access to data.

- Capacity Building: Many developing nations lack the scientific and technical expertise to participate meaningfully in deep-sea research or effectively regulate mining activities within their Extended Continental Shelves. International programs for capacity building and technology transfer are crucial for equitable engagement.

- Ethical Deliberation: The debate surrounding deep-sea mining is not solely a scientific or economic one; it is deeply ethical. Open, inclusive, and informed public discourse is essential to address questions of intergenerational equity, the intrinsic value of nature, and the appropriate relationship between humanity and the environment.

The Glomar Explorer, a vessel crafted for a hidden purpose, ultimately revealed more than just a sunken submarine. It unveiled the profound depths of human ambition, the limits of technology, and the nascent potential, and peril, of venturing into Earth’s deepest reaches. As humanity stands on the precipice of a new frontier, the lessons learned from this enigmatic ship illuminate the complex journey ahead: a journey that demands not only technological prowess but also unparalleled foresight, ecological wisdom, and a collective commitment to responsible stewardship of our planetary heritage. The deep ocean, a vibrant tapestry of life, is not merely a reservoir of resources; it is a vital component of Earth’s life support system, and its future lies in the balance of present-day choices.

WARNING: The $800 Million Mechanical Failure That Almost Started WWIII

FAQs

What was the Glomar Explorer originally built for?

The Glomar Explorer was originally built in the early 1970s by the CIA for a secret mission to recover a sunken Soviet submarine from the ocean floor. It was later repurposed for deep sea mining exploration.

How does the Glomar Explorer relate to the deep sea mining industry?

The Glomar Explorer was one of the first vessels designed to explore and potentially extract mineral resources from the deep ocean floor, marking an early attempt to develop technology for the deep sea mining industry.

What types of minerals are targeted in deep sea mining?

Deep sea mining primarily targets polymetallic nodules, cobalt-rich crusts, and seafloor massive sulfides, which contain valuable metals such as manganese, nickel, copper, cobalt, and rare earth elements.

What are some environmental concerns associated with deep sea mining?

Environmental concerns include disruption of fragile deep sea ecosystems, sediment plumes that can affect marine life, potential loss of biodiversity, and the unknown long-term impacts on ocean habitats.

Is the Glomar Explorer still in use today for deep sea mining?

No, the Glomar Explorer is no longer active. After its initial missions, it was eventually decommissioned and scrapped. However, its legacy influenced the development of modern deep sea mining technologies.