Nuclear deterrence has emerged as a pivotal concept in international relations since the advent of nuclear weapons in the mid-20th century. It refers to the strategy of preventing adversaries from taking hostile actions, particularly the use of nuclear weapons, by instilling a credible threat of retaliation. The underlying principle is that the potential for catastrophic consequences will dissuade states from engaging in aggressive behavior.

This strategy has shaped military doctrines and foreign policies, particularly among nuclear-armed states, and has played a significant role in maintaining a fragile peace during periods of heightened tension. The origins of nuclear deterrence can be traced back to the Cold War, a time characterized by intense rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union. The fear of mutual destruction led both superpowers to develop extensive arsenals of nuclear weapons, creating a precarious balance of power.

This balance, while fraught with danger, has arguably prevented direct military conflict between nuclear states. As the world continues to grapple with the implications of nuclear armament, understanding the nuances of deterrence becomes increasingly critical in navigating contemporary geopolitical landscapes.

Key Takeaways

- Nuclear deterrence relies on the threat of mutual destruction to prevent conflict.

- The concept of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) underpins global nuclear strategy.

- Nuclear weapons significantly influence international relations and power dynamics.

- Emerging technologies and proliferation pose new challenges to traditional deterrence models.

- Ethical, moral, and diplomatic factors are critical in shaping future deterrence policies.

The Concept of Mutually Assured Destruction

Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) is a cornerstone of nuclear deterrence theory, positing that if two opposing sides possess the capability to destroy each other with nuclear weapons, neither will initiate conflict. This doctrine emerged during the Cold War and was predicated on the belief that the sheer destructiveness of nuclear arsenals would act as a stabilizing force. The rationale behind MAD is simple yet profound: if both sides know that any attack would result in their own annihilation, they are less likely to engage in aggressive actions.

The implications of MAD extend beyond mere military strategy; they permeate political discourse and public perception. The concept has been both lauded and criticized, with proponents arguing that it has successfully prevented large-scale wars between nuclear powers. Critics, however, contend that relying on such a precarious balance is inherently unstable and could lead to catastrophic miscalculations.

The psychological weight of MAD has influenced not only military planning but also diplomatic negotiations, as states navigate the treacherous waters of deterrence while seeking to avoid escalation.

The Role of Nuclear Weapons in International Relations

Nuclear weapons have fundamentally altered the dynamics of international relations, serving as both instruments of power and symbols of national prestige. For many states, possessing nuclear capabilities is seen as a means to enhance security and assert influence on the global stage. The presence of nuclear weapons can deter potential aggressors and provide a sense of security against existential threats.

However, this reliance on nuclear armament also complicates diplomatic relations, as nations must grapple with the implications of proliferation and disarmament. The strategic calculus surrounding nuclear weapons often leads to complex alliances and rivalries. Countries may seek to develop their own nuclear capabilities or form partnerships with established nuclear powers to bolster their security.

As nations navigate these intricate relationships, the role of nuclear weapons remains a double-edged sword—offering security while simultaneously posing significant risks to global stability.

The Psychological and Strategic Components of Deterrence

Deterrence is not solely a matter of military capability; it encompasses psychological elements that influence decision-making at the highest levels. The perception of an adversary’s resolve and willingness to use nuclear weapons plays a crucial role in shaping deterrent strategies. Leaders must consider not only their own capabilities but also how their actions will be interpreted by others.

This psychological dimension adds layers of complexity to deterrence, as misjudgments or miscalculations can lead to unintended escalation. Strategically, effective deterrence requires clear communication and credible threats. States must demonstrate their willingness to respond decisively to aggression while ensuring that their adversaries understand the consequences of crossing certain thresholds.

This necessitates a careful balancing act—projecting strength without provoking unnecessary tensions. The interplay between psychological factors and strategic considerations underscores the importance of maintaining open lines of communication and fostering mutual understanding among nations.

The Influence of Nuclear Proliferation on Deterrence

| Concept | Description | Key Metric/Example | Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD) | Both sides possess enough nuclear weapons to destroy each other, deterring first strike. | Over 13,000 nuclear warheads globally (approximate) | Prevents nuclear war through fear of total annihilation. |

| Second-Strike Capability | Ability to respond with nuclear retaliation after absorbing a first strike. | Submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) ensure survivability. | Ensures deterrence by guaranteeing retaliation. |

| Credibility | Belief that a state will actually use nuclear weapons if attacked. | Regular military exercises and public statements. | Strengthens deterrence by convincing adversaries of resolve. |

| Deterrence Stability | Condition where neither side has incentive to strike first. | Balance of power in nuclear arsenals. | Reduces risk of accidental or preemptive nuclear war. |

| Deterrence Failure | When deterrence does not prevent nuclear conflict. | Examples: Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings (1945) | Leads to devastating consequences and loss of life. |

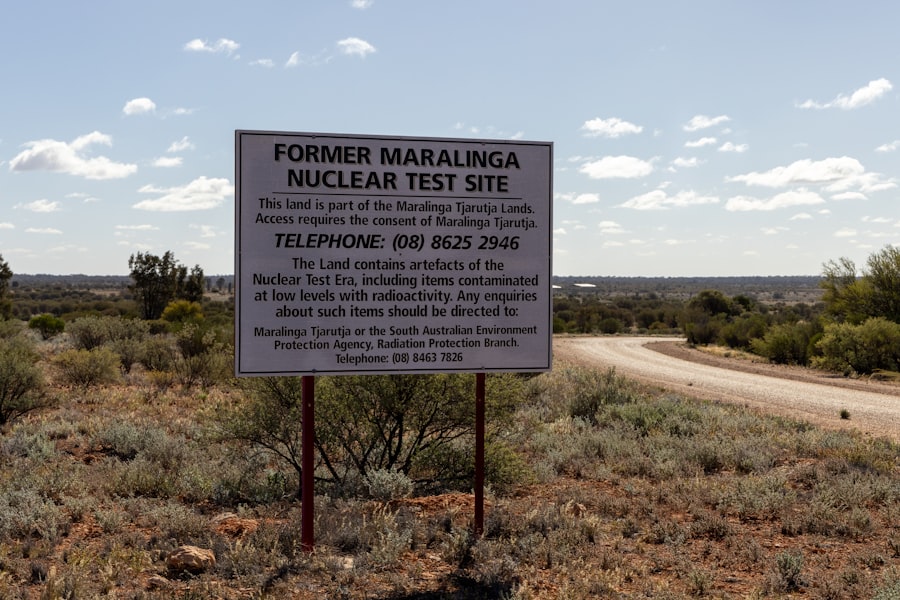

Nuclear proliferation—the spread of nuclear weapons technology and capabilities—poses significant challenges to traditional deterrence frameworks. As more states acquire nuclear weapons, the landscape becomes increasingly complex, with multiple actors possessing varying degrees of capability and intent. This proliferation can undermine established deterrent relationships, as new nuclear powers may not adhere to the same strategic calculations as their predecessors.

The emergence of additional nuclear states raises concerns about stability and escalation. Each new entrant into the nuclear club alters the balance of power, potentially leading to regional arms races and heightened tensions. Moreover, non-state actors’ interest in acquiring nuclear materials further complicates deterrence strategies, as traditional state-centric models may not adequately address these emerging threats.

As proliferation continues to shape global security dynamics, policymakers must adapt their approaches to deterrence in response to an evolving landscape.

The Evolution of Deterrence Theory

Deterrence theory has evolved significantly since its inception, reflecting changes in geopolitical realities and advancements in military technology. Initially rooted in the context of the Cold War, deterrence strategies were primarily focused on preventing direct conflict between superpowers. However, as new threats emerged—such as terrorism and cyber warfare—deterrence theory has expanded to encompass a broader range of scenarios.

Contemporary deterrence strategies now consider not only traditional state actors but also non-state entities that may possess or seek access to nuclear capabilities. This evolution necessitates a reevaluation of existing frameworks and an exploration of innovative approaches to deterrence that account for asymmetric threats. As the nature of warfare continues to change, so too must the theories that underpin deterrent strategies, ensuring they remain relevant in an increasingly complex global environment.

The Challenges of Maintaining Deterrence in the Modern World

Maintaining effective deterrence in today’s world presents numerous challenges that require careful navigation by policymakers. One significant hurdle is the increasing complexity of international relations, characterized by multipolarity and shifting alliances.

This complexity necessitates a nuanced understanding of each actor’s motivations and strategic calculus. Additionally, technological advancements pose unique challenges to deterrence strategies. The rise of cyber warfare and precision-guided munitions has altered the landscape of military engagement, blurring the lines between conventional and nuclear conflict.

States must grapple with how these developments impact their deterrent posture while ensuring that their responses remain credible and effective. As adversaries adapt their strategies in response to these changes, maintaining a robust deterrent becomes increasingly difficult.

The Impact of Emerging Technologies on Nuclear Deterrence

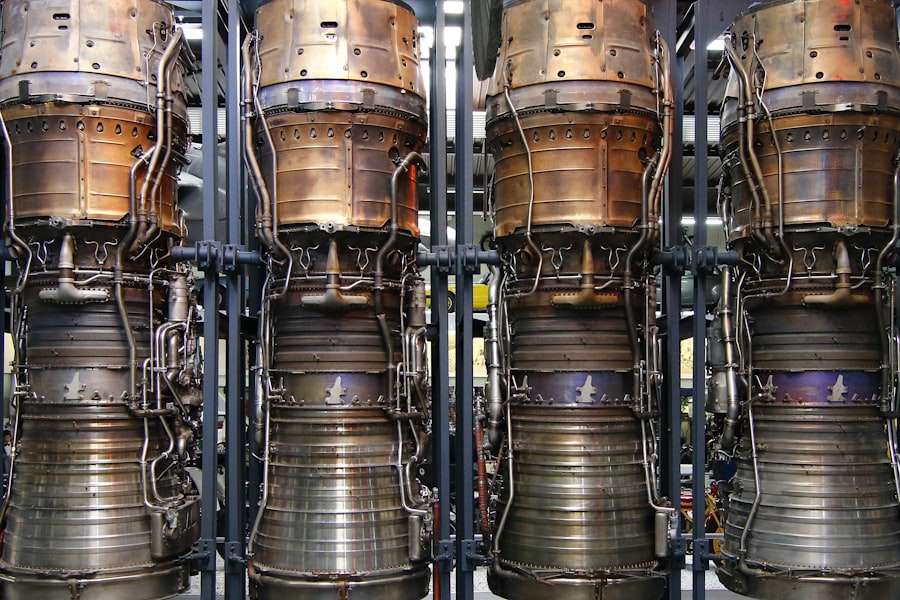

Emerging technologies are reshaping the landscape of nuclear deterrence in profound ways. Innovations such as artificial intelligence, hypersonic weapons, and advanced missile defense systems introduce new variables into strategic calculations. These technologies can enhance a state’s ability to deter adversaries or complicate existing deterrent relationships by altering perceptions of vulnerability and capability.

For instance, hypersonic weapons can potentially evade traditional missile defense systems, raising concerns about the effectiveness of existing deterrent strategies. Similarly, advancements in artificial intelligence may enable faster decision-making processes during crises but also increase the risk of miscalculation or unintended escalation. As states integrate these technologies into their military arsenals, they must carefully consider how they impact existing deterrent frameworks and adapt their strategies accordingly.

The Ethical and Moral Considerations of Nuclear Deterrence

The ethical implications surrounding nuclear deterrence are profound and multifaceted. At its core lies a moral dilemma: is it justifiable to maintain a strategy that relies on the threat of mass destruction? Critics argue that the very existence of nuclear weapons poses an existential threat to humanity and that any strategy predicated on their use is inherently flawed.

They contend that reliance on deterrence perpetuates a cycle of fear and violence that undermines global security. Conversely, proponents argue that nuclear deterrence has prevented large-scale conflicts and saved lives by maintaining stability among nuclear powers. They assert that while the moral implications are troubling, the alternative—unrestrained aggression among states—could lead to even greater suffering.

This ethical debate continues to shape discussions around disarmament and non-proliferation efforts as nations grapple with their responsibilities in an increasingly interconnected world.

The Role of Diplomacy in Deterrence Strategies

Diplomacy plays a crucial role in shaping effective deterrence strategies by fostering communication and understanding among nations. Engaging in dialogue can help clarify intentions, reduce misunderstandings, and build trust between adversaries. Diplomatic efforts can also facilitate arms control agreements that limit the proliferation of nuclear weapons and enhance stability among states.

Moreover, diplomacy can serve as a tool for de-escalation during crises when tensions run high. By providing channels for negotiation and conflict resolution, diplomatic initiatives can mitigate the risks associated with miscalculations or aggressive posturing. As global dynamics continue to evolve, integrating diplomacy into deterrent strategies will be essential for maintaining peace and stability in an increasingly complex world.

The Future of Nuclear Deterrence in a Changing Global Landscape

The future of nuclear deterrence is uncertain as geopolitical landscapes shift and new challenges emerge. As more states pursue advanced military capabilities and non-state actors seek access to nuclear materials, traditional deterrent frameworks may require significant adaptation. Policymakers must remain vigilant in assessing evolving threats while fostering international cooperation to address proliferation concerns.

In this changing environment, innovative approaches to deterrence will be essential for maintaining stability among nations. Emphasizing diplomacy alongside military preparedness can help create an atmosphere conducive to dialogue and conflict resolution. Ultimately, navigating the complexities of nuclear deterrence will require a multifaceted approach that balances security needs with ethical considerations in an increasingly interconnected world.

Nuclear deterrence logic is a complex and critical aspect of international relations, particularly in the context of maintaining peace and stability among nuclear-armed states. For a deeper understanding of this topic, you can explore the article available at this link, which delves into the principles and implications of nuclear deterrence strategies.

WATCH THIS 🎬 DEAD HAND: The Soviet Doomsday Machine That’s Still Listening

FAQs

What is nuclear deterrence?

Nuclear deterrence is a military strategy aimed at preventing an enemy from attacking by threatening them with the use of nuclear weapons in retaliation. The idea is to discourage aggression by ensuring that any attack would result in unacceptable damage to the attacker.

How does nuclear deterrence work?

Nuclear deterrence works on the principle of mutually assured destruction (MAD), where both sides possess enough nuclear weapons to destroy each other. This balance of power creates a situation where no rational actor would initiate a nuclear conflict, as it would lead to catastrophic consequences for all parties involved.

What is the logic behind nuclear deterrence?

The logic behind nuclear deterrence is based on the threat of retaliation. If a country knows that launching a nuclear attack will result in a devastating counterattack, it is less likely to initiate conflict. This creates a strategic stability where the fear of mutual destruction prevents nuclear war.

What are the key components of effective nuclear deterrence?

Effective nuclear deterrence requires credible threats, second-strike capability (the ability to respond after a nuclear attack), secure communication systems, and clear signaling to potential adversaries. It also depends on maintaining a reliable and survivable nuclear arsenal.

Is nuclear deterrence considered a stable strategy?

Nuclear deterrence is often considered stable because it prevents large-scale wars between nuclear-armed states. However, it also carries risks such as accidental launches, miscalculations, and escalation from conventional conflicts to nuclear war.

Can nuclear deterrence prevent all types of war?

Nuclear deterrence primarily deters large-scale nuclear conflict but does not necessarily prevent conventional wars, proxy wars, or other forms of conflict. It is specifically designed to prevent the use of nuclear weapons.

What are some criticisms of nuclear deterrence?

Critics argue that nuclear deterrence is risky because it relies on rational decision-making in high-stress situations, which may not always occur. There is also concern about accidents, proliferation, ethical issues, and the potential for escalation to nuclear war.

How has nuclear deterrence influenced global politics?

Nuclear deterrence has shaped international relations by creating a balance of power among nuclear-armed states. It has influenced arms control agreements, diplomatic negotiations, and military strategies since the Cold War era.

What is the difference between deterrence by punishment and deterrence by denial?

Deterrence by punishment threatens severe retaliation if attacked, while deterrence by denial aims to prevent an adversary from achieving their objectives by making an attack ineffective or too costly. Nuclear deterrence primarily relies on punishment.

Are there alternatives to nuclear deterrence?

Alternatives include disarmament, arms control agreements, confidence-building measures, and diplomatic efforts to reduce tensions. However, these approaches require mutual trust and verification mechanisms to be effective.