The hum of machinery, a persistent thrumming that penetrates the crushing pressure of the abyssal plains, is the soundtrack to a conflict far removed from the sunlit world. This is not a clash of armies on land or fleets on the surface, but a silent, high-stakes entanglement occurring in the deepest trenches of the ocean’s floor. Here, the nascent industry of deep-sea mining, a frontier of potential resource acquisition, finds itself in a gravitational pull of intrigue, its progress potentially entangled with the covert operations of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). This is the story of “The Battle Below: Deep Sea Mining vs. CIA Mission,” a narrative where geological riches meet clandestine agendas in the ultimate unknown.

For decades, the profound depths of the ocean were largely viewed as an unexplored frontier, a realm of scientific curiosity and biological marvels. However, beneath the veil of darkness and immense pressure, a wealth of mineral deposits has been identified, offering a tantalizing prospect for global resource security. These deposits, formed over geological timescales through volcanic activity, hydrothermal vents, and sedimentary processes, hold the promise of fulfilling growing international demand for critical raw materials.

Polymetallic Nodules: The Ocean’s Hidden Treasure Chest

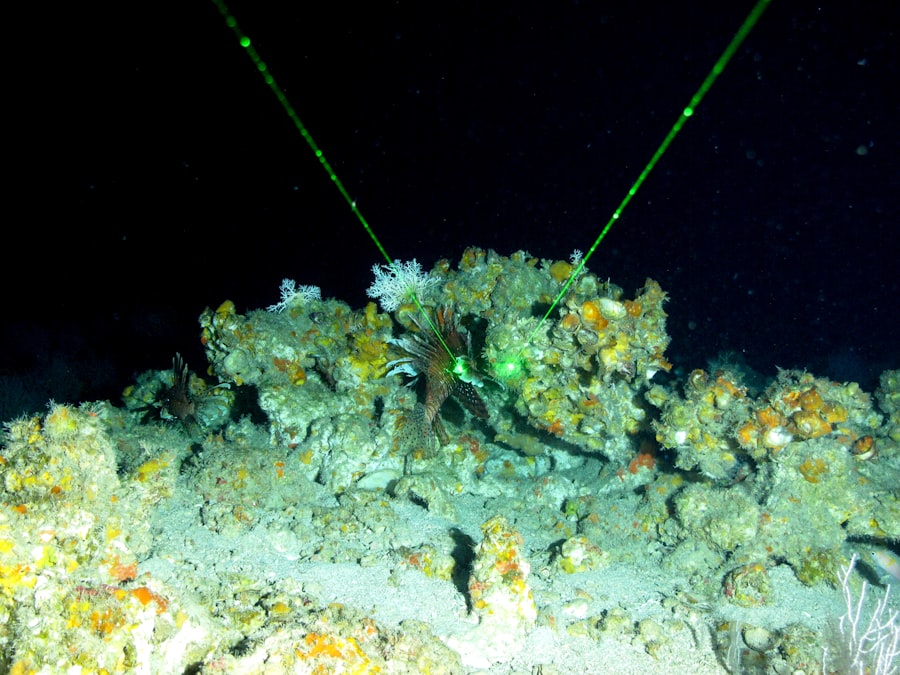

Among the most significant deep-sea resources are polymetallic nodules, often described as potato-shaped concretions that litter vast areas of the seabed, particularly in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone of the Pacific Ocean. These nodules are rich in valuable metals, including manganese, nickel, copper, and cobalt. These are precisely the elements that underpin much of our modern technology, from electric vehicle batteries to smartphones and renewable energy infrastructure.

- Composition and Formation: These nodules precipitate from seawater and sediment over millions of years, slowly accumulating metallic elements. Their unique chemical environment on the seafloor facilitates this slow but steady accretion.

- Economic Potential: The sheer scale of these deposits is staggering. Estimates suggest that the Clarion-Clipperton Zone alone could contain enough nickel to supply the world’s needs for decades, a geological bounty that has attracted the attention of mining corporations and national governments alike.

- Challenges of Extraction: Despite their immense value, the extraction of polymetallic nodules presents formidable engineering and environmental challenges. Operating at depths of 4,000 to 6,000 meters requires specialized, robust machinery capable of withstanding extreme pressure and corrosive conditions.

Seafloor Massive Sulfides: Veins of Metallic Wealth

Another key target for deep-sea mining are seafloor massive sulfides (SMS), typically found around hydrothermal vents, often dubbed “black smokers.” These vents are fissures in the Earth’s crust where superheated, mineral-rich fluids erupt, precipitating valuable metals like copper, zinc, gold, and silver.

- Hydrothermal Vent Ecosystems: SMS deposits are intimately linked to vibrant and unique ecosystems that thrive on chemosynthesis, deriving energy from chemical compounds rather than sunlight. This ecological sensitivity is a major point of contention for deep-sea mining operations.

- Concentration of Metals: While typically found in smaller, more localized deposits than nodules, SMS can be exceptionally rich in certain metals, making them attractive targets for targeted extraction.

- Technological Hurdles: Extracting SMS involves breaking apart solidified mineral deposits on active (or recently active) vent sites, a process that requires sophisticated mining technology and careful control to avoid damaging the fragile vent structures and their associated fauna.

Cobalt-Rich Crusts: A Layered Prize

Cobalt-rich crusts are another significant resource found on the flanks of seamounts and ridges, at depths ranging from a few hundred to several thousand meters. These crusts are formed by the slow precipitation of metals from seawater onto underwater rock formations.

- Cobalt as a Key Component: As the name suggests, these crusts are particularly valuable for their high cobalt content. Cobalt is a critical component in high-performance batteries, hence its strategic importance in the transition to electric mobility.

- Accessibility and Mining Methods: While potentially more accessible than nodules or SMS in some locations, mining these crusts still requires specialized equipment for scraping or cutting them from the rock formations.

- Environmental Considerations: The excavation of these crusts can impact benthic habitats and potentially release sediment into the water column, raising environmental concerns.

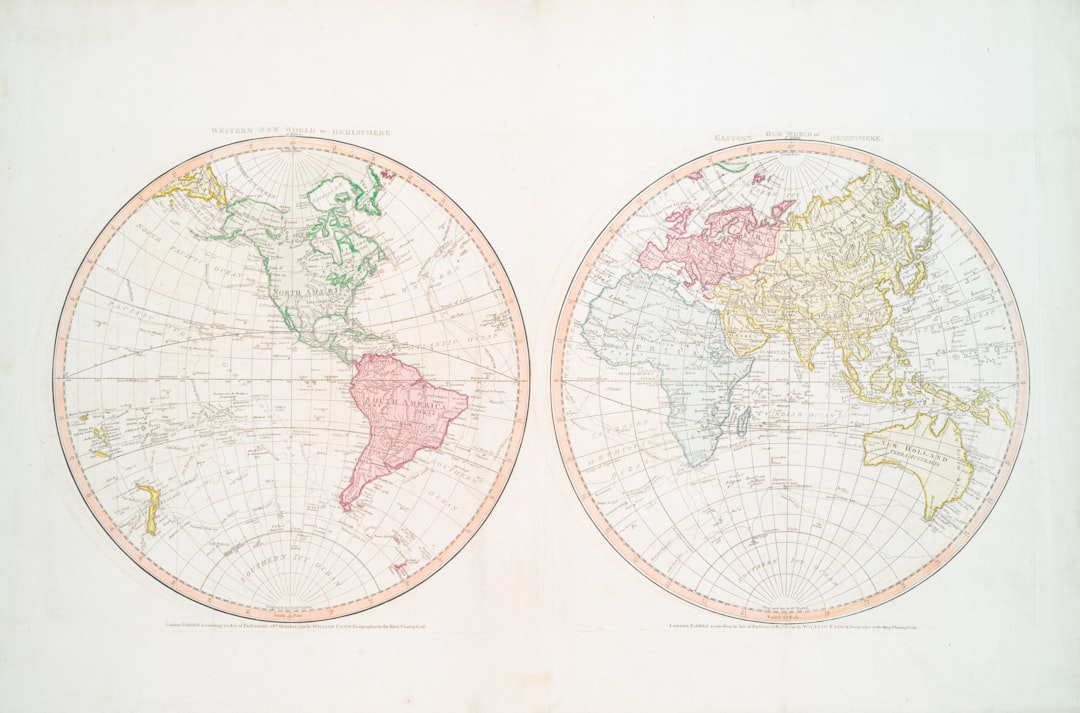

The economic drivers for deep-sea mining are compelling. As land-based reserves of certain metals become depleted or politically unstable, the vast, untapped potential of the ocean floor presents an enticing alternative. However, this drive for resources operates on a different plane than the silent, often invisible machinations of intelligence agencies.

The ongoing debate surrounding deep sea mining and its implications for environmental sustainability has garnered significant attention, particularly when juxtaposed with covert operations like those conducted by the CIA. For a deeper understanding of the geopolitical ramifications and the environmental concerns associated with such activities, you can explore a related article on this topic at In the War Room. This article delves into the intersection of resource extraction and national security, providing insights into how these two seemingly disparate issues are intricately linked.

The Shadowy Hand: Unraveling CIA Interests in the Depths

While the world gazes at the glittering promise of seabed riches, a different kind of pursuit unfolds in the same dark waters – the covert endeavors of intelligence agencies. The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), tasked with gathering information and safeguarding national security, has historically demonstrated an interest in any domain that offers strategic advantage, and the deep sea is no exception. Their motivations, shrouded in secrecy, likely extend far beyond the mere acquisition of mineral wealth, probing instead at the very fabric of global power dynamics.

Strategic Resource Security: Beyond Commerce

The CIA’s interest in deep-sea mining is unlikely to be driven by a desire to foster commercial enterprises. Instead, their focus would likely be on the strategic implications of resource control.

- Supply Chain Dominance: Ensuring a nation’s access to critical minerals is a cornerstone of economic and military security. If deep-sea mining proves viable, controlling key mining sites or technologies could grant significant leverage in global trade and manufacturing.

- Denial of Access to Adversaries: Conversely, the agency would also be concerned with preventing potential adversaries from gaining exclusive access to these vital resources. This could involve monitoring international mining efforts, assessing their technological capabilities, and potentially influencing their operations.

- Technological Superiority: The development of deep-sea mining technology is cutting-edge, pushing the boundaries of robotics, autonomous systems, and material science. The CIA would be keenly interested in understanding and potentially acquiring any advancements that offer a dual-use benefit, applicable to both civilian and military applications.

Espionage and Surveillance: The Unseen Watchers

The deep ocean, with its vastness and inherent challenges to surface observation, presents an ideal environment for clandestine activities. The CIA’s interests could extend to utilizing these environments for intelligence gathering and surveillance.

- Monitoring Submarine Activity: The deep sea is a primary theater for submarine operations, both for a nation’s own fleet and those of potential adversaries. Advanced sonar, sensor technology, and underwater infrastructure associated with mining could potentially be leveraged for enhanced submarine detection and tracking.

- Intelligence Gathering on International Operations: Should deep-sea mining ventures become widespread, they would involve international consortia, national research vessels, and commercial fleets. These operations could provide cover or unwitting assistance for intelligence gathering on the activities and intentions of other nations.

- Covert Infrastructure Placement: The remote and inaccessible nature of the deep sea could also make it an attractive location for placing covert listening devices, oceanographic sensors, or even communication nodes that would be exceptionally difficult to detect or tamper with.

Unearthing Scientific Knowledge and Technological Capabilities

Beyond direct resource acquisition and surveillance, the CIA would undoubtedly have an interest in the scientific and technological knowledge generated by deep-sea exploration and mining.

- Understanding Geopolitical Shifts: The race for deep-sea resources is already creating new geopolitical fault lines. The CIA would be focused on understanding these shifts, identifying potential flashpoints, and assessing the strategic implications for global power dynamics.

- Technological Foresight: The advancements in robotics, underwater navigation, and material science required for deep-sea mining have broader applications. The CIA would be monitoring these developments to anticipate future technological trends and their potential impact on national security.

- Mapping Uncharted Territories: Establishing a comprehensive understanding of the deep ocean floor, its geological features, and potential strategic locations is a long-term intelligence objective. Deep-sea mining projects provide an invaluable opportunity for such mapping under the guise of resource exploration.

The intersection of these two seemingly disparate worlds – the industrial pursuit of oceanic resources and the clandestine operations of a global intelligence agency – creates a complex web of potential interactions and conflicts. The stage is set for a subtle yet significant “battle below,” one fought not with bullets, but with information, technology, and strategic influence.

The Nexus of Conflict: When Mining Meets Espionage

The very nature of deep-sea mining operations, with their extensive infrastructure, large vessels, and the movement of valuable materials, creates opportunities for intelligence agencies to pursue their objectives. This is where the “battle” truly takes shape, not in direct confrontation, but in the subtle interplay of competing interests.

Covert Observation and Intelligence Gathering

The large-scale operations required for deep-sea mining naturally attract attention. Mining vessels, support ships, and deployed underwater equipment create a visible presence on the ocean’s surface and, to a lesser extent, below. This provides potential avenues for both overt and covert observation.

- Monitoring Mining Activities: The CIA would be interested in monitoring the progress, technological capabilities, and operational effectiveness of deep-sea mining projects, particularly those undertaken by potential adversaries or nations of strategic interest. This could involve satellite imagery, signals intelligence, and human intelligence assets.

- Assessing Resource Control: Intelligence agencies would seek to understand which nations and corporations are acquiring the most promising mining claims and developing the most efficient extraction technologies. This information is crucial for assessing future resource security and potential geopolitical leverage.

- Detecting Unauthorized Activities: In the vast expanse of the deep sea, it is plausible that unauthorized activities, such as illicit resource extraction or the deployment of clandestine equipment, could occur. Intelligence agencies would have an interest in detecting and deterring such activities.

Technological Infiltration and Exploitation

The cutting-edge technology employed in deep-sea mining represents a significant area of interest for intelligence agencies. This technology is complex and often proprietary, making it a prime target for espionage.

- Cybersecurity Vulnerabilities: Modern mining operations rely heavily on sophisticated digital systems for navigation, control, and data management. These systems, like any other, are potentially vulnerable to cyberattacks, offering opportunities for intelligence agencies to gain access to sensitive data or disrupt operations.

- Reverse Engineering and Technology Transfer: Understanding the intricate workings of deep-sea mining equipment, from excavators to remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), would be highly valuable. Intelligence agencies may seek to acquire prototypes, blueprints, or even engage in technical espionage to gain insights into these advanced technologies.

- Dual-Use Technologies: Many of the technologies developed for deep-sea mining, such as advanced robotics, underwater communication systems, and autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), have direct applications in military and intelligence operations. The CIA would be actively monitoring these developments for potential acquisition and integration into their own capabilities.

Strategic Leverage and Geopolitical Maneuvering

The control of deep-sea resources is inherently linked to global economic and political power. Intelligence agencies play a crucial role in advising their governments on how to navigate these emerging geopolitical landscapes.

- Influencing International Regulations: The development of international regulations governing deep-sea mining is ongoing through bodies like the International Seabed Authority (ISA). Intelligence agencies would likely provide insights and recommendations to their governments to ensure that these regulations align with national strategic interests. This could involve advocating for certain mining rights or restrictions on other nations.

- Monitoring Resource Dependencies: Understanding a nation’s reliance on specific imported minerals is a key intelligence concern. Deep-sea mining could alter these dependencies, and the CIA would be keen to assess these shifts and their implications for global supply chains.

- Preventing Resource Weaponization: In extreme scenarios, control over critical resources could be used as a tool of coercion. Intelligence agencies would be vigilant in identifying any attempts by nations to “weaponize” their access to deep-sea minerals and counter such efforts.

The presence of intelligence agencies in the vicinity of deep-sea mining operations creates a complex and potentially volatile environment. While no direct firefights are likely to occur, the battle for influence, information, and technological superiority is very much underway, playing out in the silent, crushing depths of the ocean.

Environmental Collisions: The Unintended Pawns of the Conflict

The deep-sea environment is a delicate ecosystem, largely unexplored and poorly understood. The introduction of industrial-scale mining operations, coupled with the clandestine activities of intelligence agencies, introduces a new layer of complexity and risk to this fragile realm. The very act of deep-sea mining, regardless of any covert agendas, carries inherent environmental risks that intelligence agencies may seek to exploit or simply overlook in their pursuit of strategic objectives.

Disturbing the Pristine Abyss

The introduction of heavy machinery and the disturbance of the seabed for mineral extraction can have profound and potentially irreversible impacts on deep-sea ecosystems.

- Habitat Destruction: The mining process, whether it involves scraping nodules, excavating sulfites, or cutting crusts, directly removes or significantly alters the habitat of benthic organisms. Many of these species are slow-growing and have low reproductive rates, making recovery exceptionally difficult, if not impossible.

- Sediment Plumes and Smothering: The activity of mining machinery can stir up vast plumes of sediment that can travel for considerable distances. These plumes can smother filter-feeding organisms, clog the respiratory systems of marine life, and alter the chemical composition of the water column.

- Noise and Light Pollution: The operation of mining equipment generates significant noise and light pollution in an environment that is naturally devoid of both. This can disrupt the behavior, communication, and survival strategies of deep-sea species that have evolved in perpetual darkness and silence.

The Impact of Covert Operations

While less documented, the potential environmental impact of covert intelligence operations in the deep sea also warrants consideration.

- Undisclosed Deployments: Any unauthorized deployment of sensitive underwater equipment, whether for surveillance or other purposes, could create accidental disturbances or introduce foreign contaminants into the environment. The secrecy surrounding such operations makes their environmental footprint difficult to assess.

- Accidental Damage: A collision between a clandestine submersible and a sensitive geological formation, or the accidental release of hazardous materials from a covert facility, could have localized but significant environmental consequences within the deep-sea ecosystem.

- A Lack of Oversight: The very nature of covert operations precludes any form of environmental impact assessment or mitigation planning. This means that any unintended environmental damage caused by intelligence activities would likely go unreported and unaddressed.

The Ethics of Resource Exploitation and National Security

The convergence of deep-sea mining and intelligence interests raises ethical questions about the prioritization of resource acquisition and national security over environmental preservation.

- Balancing Development and Conservation: The global push for critical minerals needed for the green transition creates a powerful incentive to overlook or downplay environmental risks. Intelligence agencies, focused on strategic advantage, may further exacerbate this imbalance.

- The Precautionary Principle: Given the vast unknowns of deep-sea ecosystems, the precautionary principle suggests that activities with the potential for significant harm should be approached with extreme caution. However, the pursuit of both economic and national security interests can undermine this principle.

- Who Bears the Cost? The environmental consequences of deep-sea mining and potentially covert operations will be borne by the deep-sea ecosystem itself, a realm that has no voice in human-driven decisions. The long-term viability of these ecosystems, which play a crucial role in global biogeochemical cycles, could be jeopardized.

The environmental consequences are not merely collateral damage; they are an intrinsic part of the complex equation. The battle below, in its broadest sense, encompasses the struggle to protect these unique environments from the unchecked ambitions of both commerce and clandestine state interests.

The ongoing debate surrounding deep sea mining has garnered significant attention, especially when juxtaposed with covert operations like those conducted by the CIA. A recent article explores the implications of underwater resource extraction and its potential geopolitical ramifications, shedding light on how nations might leverage these resources in their strategic pursuits. For a deeper understanding of these complex issues, you can read more in this insightful piece here.

The Future of the Deep: A Tenuous Balance

| Aspect | Deep Sea Mining | CIA Mission |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Extraction of minerals and metals from ocean floor | Covert intelligence gathering and operations |

| Operational Environment | Deep ocean, often 1,000+ meters below surface | Varies globally, often hostile or sensitive regions |

| Technology Used | Remotely operated vehicles, underwater drills, sensors | Surveillance equipment, cyber tools, human intelligence |

| Duration | Long-term projects spanning years | Short to medium-term missions, often classified |

| Environmental Impact | Potential disruption to marine ecosystems and biodiversity | Minimal direct environmental impact, focus on human targets |

| Legal Framework | Regulated by international maritime law and treaties | Operates under national security laws, often classified |

| Risk Factors | Technical failures, environmental hazards, regulatory challenges | Operational exposure, political fallout, mission failure |

| Economic Impact | Potential to supply critical minerals for technology and energy | Indirect impact through geopolitical influence and security |

The intertwined narratives of deep-sea mining and intelligence operations paint a complex picture of the future of the deep ocean. The forces at play are powerful, driven by economic necessity, national security imperatives, and technological ambition. Achieving a sustainable and peaceful future for this frontier demands a delicate balancing act.

Navigating the Regulatory Minefield

The International Seabed Authority (ISA) is the primary body responsible for regulating deep-sea mining in international waters. Its role is crucial in establishing environmental standards, ensuring equitable benefit sharing, and preventing undue environmental harm.

- Developing Robust Environmental Standards: The ISA must continue to develop and enforce stringent environmental regulations that are based on sound scientific evidence and the precautionary principle. This includes comprehensive environmental impact assessments, robust monitoring programs, and effective mitigation strategies.

- Transparency and Accountability: Ensuring transparency in the decision-making processes of the ISA and holding mining contractors accountable for their environmental performance are paramount. This requires open access to data and independent oversight.

- The Role of Intelligence Information: While the ISA’s mandate is primarily regulatory, the information gathered by intelligence agencies about mining operations and their potential strategic implications could, in theory, inform regulatory decisions. However, the inherent secrecy of intelligence operations makes this a complex and problematic avenue.

The Ethics of Resource Control

The global demand for critical minerals will not abate easily. The question then becomes how to meet this demand without sacrificing the integrity of the deep-sea environment or creating new geopolitical flashpoints.

- Diversifying Resource Acquisition: Reliance on deep-sea minerals should not be the sole strategy for securing critical raw materials. Continued investment in terrestrial mining, recycling technologies, and the development of alternative materials is essential to reduce pressure on the fragile deep-sea environment.

- International Cooperation and Conflict Prevention: Without clear and equitable international agreements, the race for deep-sea resources could lead to increased tensions and potential conflicts. Fostering cooperation and dialogue among nations is vital to prevent the deep sea from becoming a new arena for geopolitical rivalry.

- The Imperative of Scientific Understanding: Our understanding of deep-sea ecosystems is still in its infancy. Continued scientific research is not a luxury but a necessity. This research should inform all decisions regarding resource extraction and environmental protection, ensuring that our actions are guided by knowledge, not just the pursuit of gain.

The Unseen Battles Continue

The covert activities of intelligence agencies are unlikely to cease. Their presence in the deep sea, whether directly linked to mining or pursuing other strategic objectives, will continue to shape the operational landscape.

- The Need for Vigilance: The international community, and particularly bodies like the ISA, need to be aware of the potential for intelligence activities to influence or undermine regulatory processes. While direct intervention is unlikely, the awareness of these unseen battles can foster a more cautious and informed approach to deep-sea governance.

- Focus on Transparency and Peace: Ultimately, the most effective counter to clandestine influence is the establishment of robust, transparent, and cooperative international frameworks. When development and regulation are conducted in the open, with all stakeholders having a voice, the space for covert manipulation diminishes.

- A Long and Winding Road: The future of deep-sea mining, and indeed the deep ocean itself, will be shaped by a complex interplay of economic forces, national security interests, scientific understanding, and ethical considerations. The battles below, both the overt and the covert, will continue to unfold, reminding us that the deepest parts of our planet are not exempt from the ambitions and rivalries that define the human world.

The deep sea, a realm of profound mystery and immense potential, stands at a critical juncture. The pursuit of its mineral wealth, intertwined with the silent machinations of intelligence agencies, presents a formidable challenge. The future of this largely unexplored frontier hinges on humanity’s ability to navigate these complex currents, ensuring that the pursuit of progress does not lead to irreversible environmental damage or escalate geopolitical tensions. The battle below is far from over; it is a continuing testament to the enduring human drive for resources and security, played out in the ultimate frontier, far from the light of day.

WATCH NOW ▶️ SHOCKING: How The CIA Stole A Nuclear Submarine

FAQs

What is deep sea mining?

Deep sea mining is the process of retrieving mineral deposits from the ocean floor, typically at depths of 200 meters or more. It targets valuable resources such as polymetallic nodules, cobalt-rich crusts, and seafloor massive sulfides, which contain metals like copper, nickel, cobalt, and rare earth elements.

What is a CIA mission?

A CIA mission refers to an operation conducted by the Central Intelligence Agency, the United States’ foreign intelligence service. These missions can involve intelligence gathering, covert operations, counterterrorism, and other activities aimed at protecting national security interests.

How do deep sea mining and CIA missions differ in purpose?

Deep sea mining is primarily an industrial and commercial activity focused on resource extraction for economic gain. In contrast, CIA missions are intelligence and security operations aimed at gathering information, conducting espionage, or executing covert actions to support national security objectives.

Are there any connections between deep sea mining and intelligence agencies like the CIA?

While deep sea mining is mainly a commercial and environmental issue, intelligence agencies may monitor or gather information related to deep sea mining activities for geopolitical or security reasons. However, deep sea mining itself is not a direct function of intelligence agencies like the CIA.

What are the environmental concerns associated with deep sea mining?

Deep sea mining poses potential risks to marine ecosystems, including habitat destruction, sediment plumes, and disruption of deep-sea species. The long-term environmental impacts are not fully understood, leading to calls for cautious regulation and further scientific research before large-scale mining operations proceed.