You stand at the precipice of the unknown, a vast, dark expanse stretching before you. For millennia, this realm, comprising over 70% of our planet’s surface, remained a mystery, a liquid labyrinth where light relinquished its dominion. But now, you hold the key to unlocking its secrets: sonar technology. This article will illuminate how sonar acts as your eyes and ears beneath the waves, transforming the inky blackness into a canvas of understandable data.

At its core, sonar operates on a principle as old as nature itself: echolocation. Think of a bat navigating a darkened cave, emitting a series of clicks and interpreting the returning echoes to build a mental map of its surroundings. Sonar technology replicates this biological feat with sophisticated engineering.

The Sonic Pulse: Your Invisible Touch

Sonar Transducers: The Heartbeat of the System

Your sonar system relies on transducers, the crucial components that both emit sound and receive its reflections. These devices are like your vocal cords and ears, working in tandem to sense the environment. When you activate your sonar, a transducer, often a piezoelectric crystal, is stimulated, causing it to vibrate rapidly and emit a focused burst of sound waves, known as a ping. This ping is your invisible probe, venturing out into the water.

Acoustic Waves: The Messengers of the Deep

The ping isn’t just noise; it’s a precisely controlled pulse of acoustic energy. These sound waves travel through the water at a speed dependent on its temperature, salinity, and pressure. As these waves encounter objects within the water column – be it the seabed, a submerged vessel, a school of fish, or geological formations – they are reflected back towards your sonar. These returning echoes are the vital data your system needs.

The Return Journey: Listening to the Whispers

Once the sound waves bounce off an object, they travel back to your sonar system. Another transducer, or sometimes the same one used in a receiving mode, picks up these faint returning echoes. The timing of these echoes is paramount. The longer it takes for an echo to return, the farther away the object is. This simple yet ingenious principle allows you to determine the distance to any submerged entity.

Interpretation and Display: Translating Sound into Sight

The raw data of returning echoes, measured in milliseconds, is not immediately comprehensible. Your sonar system’s processing unit acts as your interpreter. It analyzes the timing, intensity, and frequency of the returning signals. This raw information is then transformed into a visual representation that you can understand, typically displayed on a screen. This can range from a simple depth reading to complex graphical renditions of the underwater terrain.

Sonar technology has revolutionized underwater exploration and surveillance, providing critical insights into marine environments and enhancing naval operations. For a deeper understanding of its applications and advancements, you can read a related article that discusses the latest innovations in sonar systems and their impact on maritime security. Check it out here: Sonar Technology Innovations.

The Diverse Toolkit: Types of Sonar Systems

Just as there are different ways to explore the world above water, so too are there various sonar technologies, each optimized for specific tasks and environments. You wouldn’t use a microscope to survey a mountain range, and similarly, different sonar systems are suited for different underwater investigations.

Active Sonar: The Proactive Explorer

Active sonar is your proactive approach to mapping the underwater world. It involves both transmitting a sound pulse and listening for its echo. This is akin to calling out in a dark room and listening for the sound of your voice bouncing off the walls.

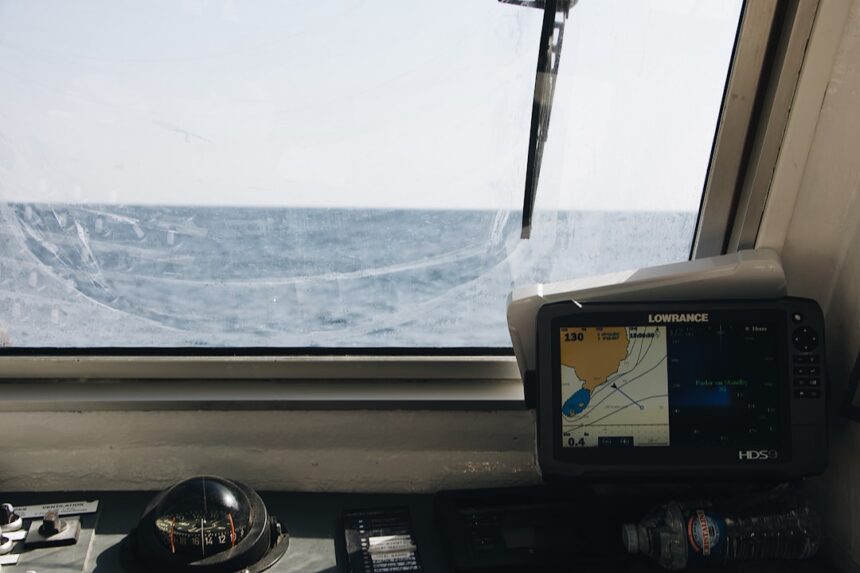

Hull-Mounted Sonar: Your Vessel’s Integrated Navigator

Often mounted directly onto the hull of a ship or submarine, these transducers are perpetually submerged, ready to emit and receive. They are the workhorses for general navigation and surveying, providing continuous information about the water depth directly beneath your vessel. You’ll find these on everything from small research boats to large naval warships.

Towed Sonar Arrays: Extending Your Sonic Reach

For deeper or wider area surveys, you might employ towed sonar arrays. These are long cables, equipped with multiple sonar transducers, that are pulled through the water behind your vessel. This configuration allows you to cover a larger swathe of the seabed in a single pass and can often achieve greater depths than hull-mounted systems, effectively extending your visual reach into the abyssal plains.

Side-Scan Sonar: Painting the Seabed Picture

Side-scan sonar is a specialized form that literally “scans” the sides of the seabed. Imagine your sonar emitting beams of sound downwards and outwards to either side, like a floodlight illuminating a landscape. The returning echoes build up a detailed, photographic-like image of the seafloor, revealing features such as shipwrecks, pipelines, and geological formations with remarkable clarity, even in murky waters. This is your tool for detailed seabed archaeology or infrastructure inspection.

Multi-Beam Echosounders: Creating 3D Depths

Multi-beam systems take the concept of side-scan further by emitting a fan of sound beams, typically covering a wide swath of the seabed. By analyzing the echoes from each individual beam, you can create highly detailed three-dimensional bathymetric maps, depicting the contours and topography of the underwater landscape with incredible precision. This is essential for nautical charting and in-depth geological surveys.

Passive Sonar: The Silent Listener

Passive sonar, in contrast to active sonar, operates without transmitting its own sound. It’s like sitting in a quiet forest and listening to the rustling leaves, animal calls, and distant sounds. This technology focuses solely on detecting and analyzing sounds that are already present in the marine environment.

Hydrophones: Your Underwater Ears

In essence, passive sonar systems are networks of hydrophones – underwater microphones. These sensitive devices are designed to capture a wide range of acoustic signals. They are crucial for activities where revealing your own presence could be detrimental, such as in military surveillance or wildlife observation.

Signal Analysis: Identifying the Source

The challenge with passive sonar lies in distinguishing and identifying the source of the detected sounds. Sophisticated algorithms are employed to analyze the characteristics of the sound waves, such as their frequency, modulation, and intensity. This allows you to identify whether a detected sound originates from a passing ship, a marine mammal, or even an underwater geological event. This is your detective work in the acoustic realm.

Sonar in Action: Applications Across the Spectrum

The versatility of sonar technology means it plays a critical role in a multitude of fields, from scientific research to commercial operations and national security. You’ll find sonar instruments diligently at work, pushing the boundaries of our understanding and capabilities.

Scientific Exploration: Charting the Unknown Depths

Marine scientists rely heavily on sonar to explore and understand the ocean’s vast ecosystems and geological processes.

Bathymetric Mapping: Creating the Ocean’s Topography

Sonar is your primary tool for creating bathymetric maps, which are essentially underwater topographical maps. These charts detail the depth contours of the ocean floor, revealing the presence of seamounts, trenches, canyons, and continental shelves. This information is foundational for understanding oceanography, plate tectonics, and marine habitat distribution.

Seabed Characterization: Understanding the Ocean Floor

Beyond just depth, sonar, particularly side-scan and multi-beam systems, can characterize the composition and texture of the seabed. This allows scientists to differentiate between soft sediment, rocky outcrops, or areas with specific mineral deposits. This is vital for understanding sediment transport, identifying potential resource locations, and studying the benthic environments where marine life thrives.

Underwater Archaeology: Unearthing Lost Histories

For underwater archaeologists, sonar is an indispensable tool for locating and surveying submerged historical sites. Shipwrecks, ancient ruins, and other artifacts can be detected and mapped without disturbing the fragile underwater environment. Side-scan sonar, in particular, can reveal the outline of a wreck or structure on the seabed from hundreds of meters away, guiding your initial investigations.

Marine Biology Research: Observing the Silent Majority

Sonar is also used to study marine life, albeit indirectly. Certain types of sonar can detect and track schools of fish, estimate their biomass, and even provide insights into their behavior. While direct observation of all marine life through sonar is limited, it’s invaluable for understanding their habitats and population dynamics, especially in deep-sea environments where visual observation is impractical.

Commercial Applications: Navigating and Exploiting Resources

The commercial world benefits significantly from sonar’s ability to navigate safely and exploit marine resources efficiently.

Navigation and Charting: Sailing with Confidence

For mariners, accurate nautical charts are paramount for safe passage. Sonar systems, especially multi-beam echosounders, are the backbone of modern charting operations, providing the precise depth data needed to create and update these vital maps, preventing costly groundings and ensuring efficient shipping routes.

Offshore Industry Operations: Building Beneath the Waves

The offshore oil and gas industry, as well as renewable energy sectors (like offshore wind farms), rely heavily on sonar. Sonar surveys are essential for site selection, assessing seabed conditions for foundation placement, and inspecting underwater pipelines and infrastructure. You can think of sonar as the surveyor who ensures the stability of every underwater construction project.

Fisheries Management: Understanding the Catch

Fishing fleets use sonar to locate fish shoals, improving their efficiency and reducing bycatch. Sounders that can differentiate between different types of seabed and even identify the size and density of fish schools are crucial for sustainable fishing practices.

Underwater Construction and Maintenance: Working in the Dark

When deploying or maintaining underwater structures, sonar provides the necessary visual cues for remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) and divers. It helps them navigate complex underwater environments, locate specific targets, and perform intricate tasks with precision.

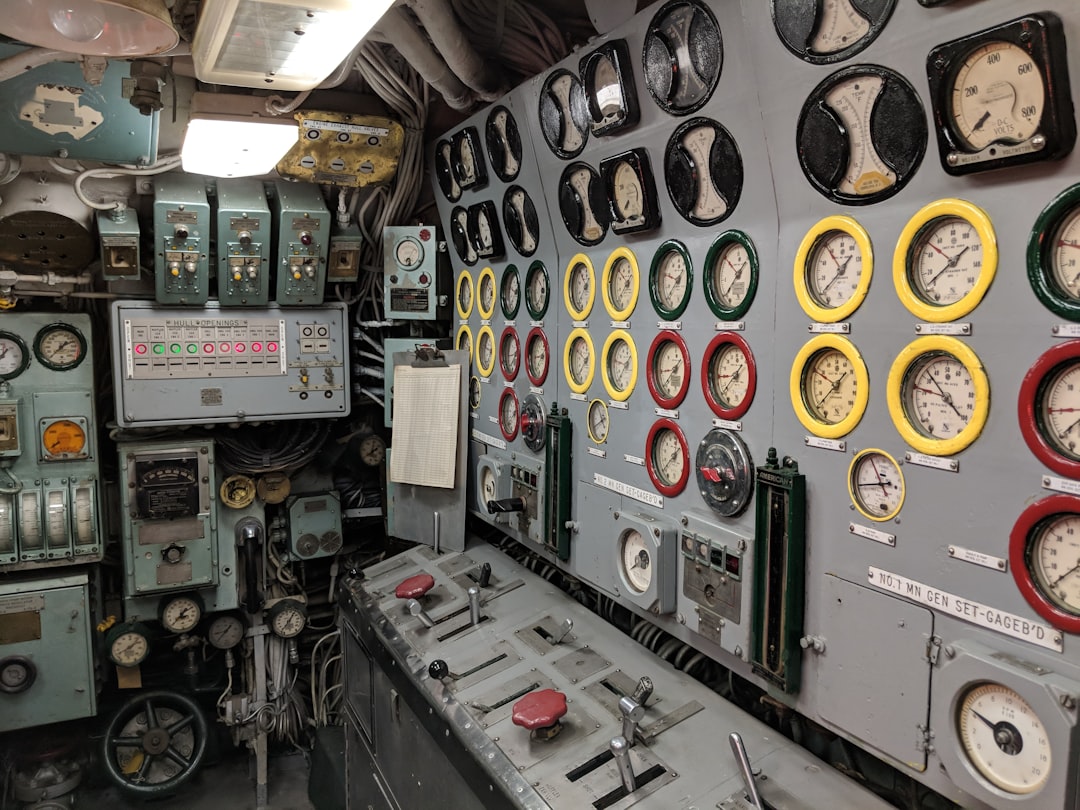

Defense and Security: The Invisible Guardians

In the realm of defense and security, sonar technology is a critical component of naval operations.

Submarine Detection and Tracking: The Silent Hunt

The primary application of sonar in naval warfare is submarine detection. Active sonar can be used to “ping” for submarines, while passive sonar allows vessels to listen for the tell-tale sounds of a submarine’s machinery. This is a constant cat-and-mouse game played out in the acoustic depths.

Mine Warfare: Clearing the Path

Sonar systems, particularly side-scan sonar, are instrumental in detecting underwater mines. Identifying these dangerous obstacles allows for their safe disposal, clearing shipping lanes and ensuring the safety of naval operations.

Surveillance and Reconnaissance: Keeping Watch

Passive sonar arrays can be deployed to monitor underwater activity in strategic areas, providing valuable intelligence on the movements of other vessels and potential threats. This is your silent sentry, constantly listening for any unusual acoustic signatures.

Advances and Future of Sonar Technology: Evolving the Sonic Senses

Sonar technology is not a static field; it is a dynamic area of continuous innovation, constantly pushing the boundaries of what’s possible. As computing power increases and new materials are developed, the capabilities of sonar systems are expanding exponentially.

Enhanced Signal Processing: Smarter Interpretation

Machine Learning and AI: Deciphering Complexity

The integration of machine learning and artificial intelligence is revolutionizing sonar signal processing. These advanced algorithms can learn to distinguish subtle acoustic signatures, identify new types of underwater objects, and filter out environmental noise with unprecedented accuracy. This is akin to training your sonar to become an expert detective, capable of recognizing patterns that were previously invisible.

Higher Frequencies and Resolution: Seeing Finer Details

Research into higher frequency sonar systems promises even greater detail and resolution in underwater imaging. While higher frequencies generally have shorter ranges, they can reveal finer seabed features and smaller objects with remarkable clarity, opening up new possibilities for detailed surveys and the detection of very small targets.

Miniaturization and Autonomous Systems: Ubiquitous Sensing

The trend towards miniaturization is leading to the development of smaller, more portable sonar devices that can be deployed from a wider range of platforms. Coupled with advances in autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), this allows for widespread, persistent underwater sensing and mapping without the need for constant human supervision. Imagine swarms of tiny sonar robots autonomously mapping vast ocean floors.

Biomimetic Sonar: Learning from Nature

Scientists are increasingly looking to nature for inspiration in sonar design. The highly sophisticated echolocation systems of dolphins and whales, with their ability to discern fine details and navigate complex environments, are providing valuable insights into the development of more advanced and efficient sonar technologies. You are essentially reverse-engineering the ocean’s master sonic navigators.

New Transducer Technologies: More Efficient Transmissions

The development of new transducer materials and designs is leading to more efficient sound generation and reception. This means sonar systems can be more powerful, more energy-efficient, and capable of operating in more challenging conditions.

Sonar technology has become increasingly vital in various fields, from marine exploration to military applications. For those interested in a deeper understanding of how sonar systems operate and their impact on modern warfare, a related article can provide valuable insights. You can read more about this fascinating topic in the article on sonar advancements found here. This resource delves into the latest developments and practical uses of sonar, highlighting its significance in today’s technological landscape.

Challenges and Limitations: The Inherent Boundaries of Sound

| Metric | Description | Typical Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency Range | Operating frequency of sonar waves | 1 – 500 | kHz |

| Range Resolution | Minimum distance between two objects to be distinguished | 0.1 – 1 | meters |

| Maximum Detection Range | Farthest distance at which sonar can detect objects | 1000 – 20000 | meters |

| Beamwidth | Angular width of the sonar beam | 1 – 30 | degrees |

| Pulse Duration | Length of the sonar pulse | 0.1 – 10 | milliseconds |

| Sound Speed in Water | Speed of sound propagation in seawater | 1500 | m/s |

| Source Level | Intensity of the sonar signal at 1 meter | 180 – 230 | dB re 1 μPa @ 1m |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | Ratio of signal power to background noise | 20 – 40 | dB |

Despite its remarkable capabilities, sonar technology is not without its limitations. Understanding these constraints is crucial for interpreting sonar data accurately and for recognizing when other technologies or methods might be more appropriate. These are the inherent challenges you face when trying to perceive the unseen.

The Sound Shadow: Obstacles and Absorption

Sound waves, like light, can be blocked or absorbed by certain materials. Dense geological formations or thick layers of sediment can create “shadows” where sonar signals cannot penetrate, masking what lies beneath. Similarly, some materials are highly absorbent of sound, making them difficult to detect clearly.

Acoustic Ambiguity: The Problem of Identity

While sonar can accurately determine the distance, size, and general shape of an object, precisely identifying its material composition or function based solely on sound can be challenging. A submerged piece of metal and a large rock might produce similar echoes, requiring further investigation or a combination of sonar types for positive identification.

Environmental Factors: The Dynamic Medium

The effectiveness of sonar is influenced by various environmental factors. Changes in water temperature, salinity, and pressure can alter the speed of sound, affecting distance calculations. The presence of marine life, plankton blooms, or gas bubbles in the water can also create acoustic clutter, interfering with the sonar signal and degrading its quality.

Range Limitations: The Finite Reach of Sound

Every sonar system has a practical range limit. The further sound waves travel, the weaker their echoes become due to spreading and absorption. This means that while deep-sea sonar can reach impressive depths, the resolution and clarity of the returned data may decrease significantly with distance.

The Impact on Marine Life: A Delicate Balance

It is important to acknowledge that high-intensity active sonar, particularly in military applications, can have negative impacts on marine mammals. The loud sounds can disrupt their communication, navigation, and foraging behaviors, and in extreme cases, have been linked to strandings. This is an ongoing area of research and conservation effort, striving to balance operational needs with the protection of marine ecosystems.

Conclusion: The Ever-Expanding Horizon of Sonar

You have journeyed through the fundamental principles of sonar, explored its diverse applications, and glimpsed its future potential. Sonar technology has transformed our understanding of the underwater world, turning a realm of impenetrable darkness into a landscape of discoverable data. From charting the deepest trenches to locating lost shipwrecks, to safeguarding our coastlines, sonar acts as your tireless extension, allowing you to probe, map, and understand the 70% of our planet that lies hidden beneath the waves. As technology continues to advance, the horizon of what you can explore with sonar will only continue to expand, promising deeper insights and more profound discoveries in the years to come.

WATCH NOW▶️ Submarine detection technology history

FAQs

What is sonar technology?

Sonar technology is a method that uses sound waves to detect and locate objects underwater. It works by emitting sound pulses and measuring the time it takes for the echoes to return after bouncing off objects.

How does sonar technology work?

Sonar systems send out sound waves that travel through water. When these waves hit an object, they reflect back to the sonar receiver. By calculating the time delay and the strength of the returned signal, the system can determine the distance, size, and shape of the object.

What are the main types of sonar?

There are two primary types of sonar: active and passive. Active sonar emits sound pulses and listens for echoes, while passive sonar only listens for sounds made by other objects, such as marine life or submarines.

What are common applications of sonar technology?

Sonar is widely used in navigation, underwater mapping, fishing, submarine detection, and scientific research. It helps in locating underwater hazards, mapping the ocean floor, and studying marine life.

What are the limitations of sonar technology?

Sonar performance can be affected by water conditions such as temperature, salinity, and pressure. It may also have difficulty detecting objects in noisy environments or at great distances due to signal attenuation and interference.