The cold, crushing abyss of the ocean depths is a realm where silence is paramount and endurance is key. To navigate this hostile frontier, the modern nuclear submarine is a marvel of engineering, its heart a compact, powerful reactor that grants it an almost boundless range. Yet, beneath the polished steel and sophisticated sonar arrays, the technology that propels these vessels remains shrouded in a veil of secrecy, a testament to the strategic importance and technical complexity of nuclear submarine propulsion. These are not mere ships that swim; they are the epitome of controlled power, a silent predator in the deep, and their propulsion systems are the wellspring of this ability.

At the core of any nuclear submarine’s operational capability lies its nuclear reactor. Unlike its land-based counterparts, the reactors designed for submarines are characterized by their compact size, robust construction, and ability to operate reliably under extreme conditions, mirroring the pressure cooker environment of the deep sea. These reactors are the engine room of the submarine, the fiery crucible that generates the immense energy required for sustained underwater operations. The fundamental principle remains the same as in any nuclear power plant: harnessing the energy released from nuclear fission. However, the practical implementation for a mobile, submerged platform presents a unique set of challenges and solutions.

The Physics of Fission: The Source of Power

The process of nuclear fission is the bedrock of nuclear submarine propulsion. It involves splitting the nuclei of heavy atoms, typically uranium, releasing a significant amount of energy in the form of heat and neutrons. This chain reaction, when carefully controlled, becomes a self-sustaining process, akin to a meticulously managed wildfire. The fissile material, usually enriched uranium, is arranged in fuel assemblies. When a neutron strikes a uranium atom, it causes fission, releasing more neutrons and a burst of thermal energy. These newly released neutrons can then strike other uranium atoms, perpetuating the chain reaction. The control rods, made of neutron-absorbing materials like cadmium or boron, are crucial for regulating this process. Inserting them into the reactor core slows down the chain reaction, while withdrawing them speeds it up. This delicate ballet of neutron capture and release is the symphony that powers the submarine.

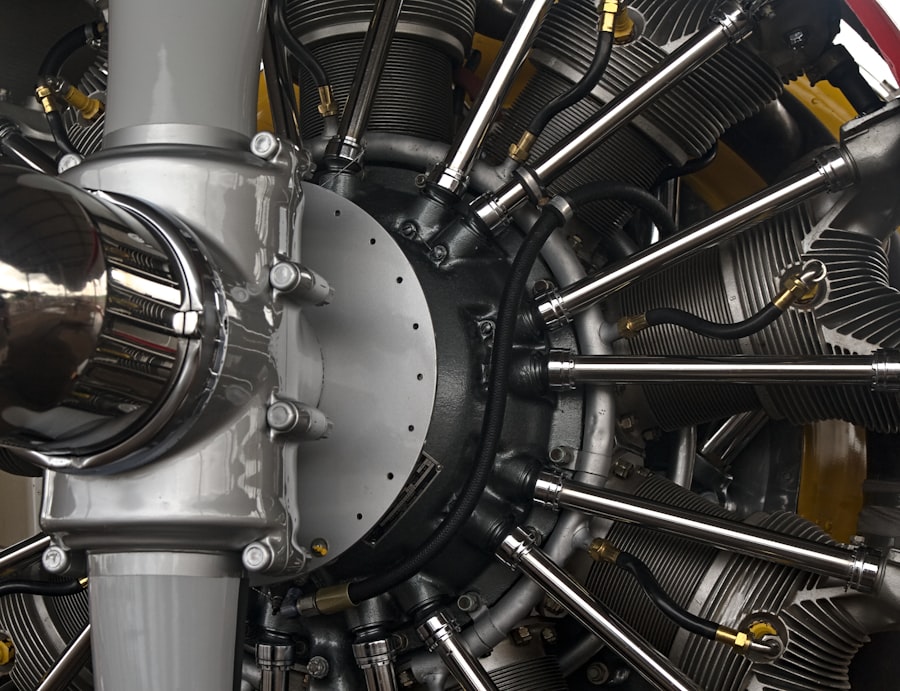

Pressurized Water Reactors (PWRs): The Dominant Technology

The vast majority of nuclear submarines in service today, across numerous navies, utilize Pressurized Water Reactors (PWRs) as their primary propulsion system. This choice is not arbitrary; PWRs offer a compelling balance of power, safety, reliability, and operational longevity. In a PWR, the reactor core heats water under high pressure. This primary coolant loop, forced to remain liquid, circulates through the reactor core, absorbing the heat generated by fission. This superheated, pressurized water then transfers its thermal energy to a secondary loop of water, causing it to boil and produce steam. This steam, at high pressure, is then directed to drive turbines, which in turn power the submarine’s propeller shafts. The water acts as both a coolant and a moderator, slowing down neutrons to increase the likelihood of fission. This elegant simplicity, in principle, belies the engineering prowess required to miniaturize and harden such a system for naval applications.

The Enriched Uranium Fuel: The ‘Juice’ of the Reactor

The ‘juice’ that fuels these reactors is highly enriched uranium (HEU). Unlike the low-enriched uranium (LEU) used in commercial power plants, submarine reactor fuel is enriched to a much higher percentage of the fissile isotope Uranium-235. This higher enrichment allows for a more compact core and provides greater power density, crucial for fitting the reactor into a submarine’s confined hull. The enrichment process is a complex and sensitive undertaking, akin to meticulously separating a rare ingredient in a vast culinary endeavor. The specific enrichment levels are highly classified, representing a significant aspect of national security. The fuel assemblies are designed for longevity, allowing submarines to operate for years, even decades, without refueling, a crucial advantage in extended deployments.

Control Rods: The Fine-Tuning Mechanism

As mentioned, control rods are the unseen hands that guide the nuclear reaction. They are meticulously engineered to absorb neutrons, effectively dampening the fission process. By precisely controlling the insertion and withdrawal of these rods, operators can manage the reactor’s power output, from creeping silently at slow speeds to delivering surge power for evasive maneuvers. The system is designed with inherent safety features; for example, if power is lost, the rods will automatically drop into the core, shutting down the reactor. This fail-safe mechanism is a testament to the rigorous safety protocols embedded in nuclear submarine design.

Other Reactor Designs: Exploring Alternative Avenues

While PWRs dominate, other reactor designs have been explored and, in some cases, implemented for submarine propulsion. These represent attempts to optimize specific performance characteristics or address perceived limitations of the PWR. Discussions around these alternatives often touch upon enhanced efficiency, reduced size, or different operational profiles.

Small, Heavy Water Reactors: A Niche Application

A less common, but noteworthy, alternative involves heavy water reactors. Heavy water, composed of deuterium oxide instead of ordinary hydrogen oxide, is a more efficient moderator than light water. This allows for the use of unenriched or low-enriched uranium fuel, a significant advantage in terms of fuel accessibility and proliferation concerns. However, heavy water reactors tend to be larger and can present their own set of engineering challenges for submarine integration. Their use has been more characteristic of specific national programs with distinct strategic priorities.

Advanced Reactor Concepts: The Future Frontier

The pursuit of enhanced performance and safety continues to drive research into advanced reactor concepts for submarine applications. These efforts often focus on concepts like liquid metal-cooled reactors or small modular reactors (SMRs) that promise higher power densities, improved efficiency, and even more inherent safety features. The development of these technologies is a long-term endeavor, pushing the boundaries of materials science and nuclear engineering, and could redefine the future of underwater warfare.

Recent discussions surrounding nuclear submarine propulsion secrets have been fueled by an intriguing article that delves into the advancements and challenges faced in this critical area of naval technology. For those interested in exploring the complexities of nuclear propulsion systems and their implications for modern warfare, the article can be found here: Nuclear Submarine Propulsion Insights. This resource provides a comprehensive overview of the innovations that have shaped submarine capabilities and the ongoing efforts to maintain strategic advantages in underwater operations.

The Heat Transfer System: From Fission to Thrust

The heat generated by the nuclear reactor is the raw material for propulsion. However, it cannot be directly used to turn a propeller. A sophisticated heat transfer system acts as the intermediary, converting the thermal energy into the mechanical force needed to move the submarine. This intricate network of pipes, pumps, and heat exchangers is the unseen circulatory system that allows the submarine to breathe underwater.

The Primary Coolant Loop: Absorbing the Heat

The primary coolant loop is the first stage in this thermal journey. Here, a fluid – typically treated water in a PWR – is circulated through the reactor core to absorb the immense heat produced by fission. This fluid becomes superheated and highly pressurized, a volatile concoction that must be managed with extreme precision. The design of the pumps and piping in this loop is critical; they must withstand high temperatures, pressures, and radiation, forming a robust containment for this energetic fluid.

The Secondary Loop and Steam Generation: Powering the Turbines

The superheated fluid from the primary loop then enters a heat exchanger, a vital component where its thermal energy is transferred to a separate secondary loop of water. This second loop is designed to boil, producing high-pressure steam. This steam then becomes the workhorse of the propulsion system. The efficiency of this heat exchange is paramount, as it directly impacts the amount of steam generated and, consequently, the power available for propulsion.

Turbines and Gears: The Mechanical Link to Motion

The generated steam is directed to drive turbines. These are essentially rotary engines, where the high-pressure steam expands and rotates spinning blades. These turbines are connected via gearboxes to the submarine’s propeller shafts. The gearboxes are essential for reducing the high rotational speed of the turbines to a slower, more efficient speed required by the propellers for optimal thrust. This entire mechanical assembly is a symphony of precision engineering, where every gear tooth and turbine blade plays a critical role.

Power Conversion and Electrical Systems: More Than Just Propellers

While turning propellers is the primary goal, a nuclear submarine’s reactor also powers a vast array of auxiliary systems that are essential for its operation and the well-being of its crew. This multifaceted power distribution system is as vital as the propulsion itself.

Generating Electricity: The Unsung Heroes

Beyond directly powering the propulsion turbines, a significant portion of the steam generated is used to drive turbogenerators, producing electricity. This electricity is the lifeblood of the submarine, powering everything from navigation and communication equipment to life support systems, sonar, weapons systems, and the crew’s living quarters. The reliability and redundancy of these electrical generation systems are paramount, ensuring continuous operation even under strenuous conditions.

Battery Banks: The Silent Reserve

Nuclear submarines are not solely reliant on their reactors for immediate power needs. Large, high-capacity battery banks are a critical component of their electrical system. These batteries serve multiple purposes. They provide power during periods when the reactor is shut down or operating at very low power, allowing for silent running and maximum stealth. They also act as a buffer, absorbing power fluctuations and providing a stable electrical supply to sensitive equipment. In essence, they are the submarine’s silent reserve, a hidden store of energy for critical moments.

Power Distribution and Control: The Nervous System

The management of this electrical power is handled by a sophisticated power distribution and control system. This network of switchboards, circuit breakers, and control consoles is the submarine’s nervous system, directing electricity where it is needed most. Redundant power lines and automatic load shedding mechanisms ensure that critical systems remain operational even in the event of damage or failure.

Torque and Thrust: The Final Frontier of Movement

The ultimate manifestation of the nuclear reactor’s energy is the torque and thrust generated to propel the submarine through the water. This is where the complex interplay of engineering disciplines culminates in purposeful motion.

Propeller Design: The Blades of Propulsion

The propellers themselves are meticulously designed hydrodynamic entities. Their shape, size, and pitch are optimized for efficient thrust generation at various speeds and depths. Modern submarine propellers often feature advanced designs, such as skewed or scimitar-shaped blades, to reduce cavitation (the formation of bubbles due to low pressure, which creates noise and reduces efficiency) and minimize their acoustic signature. The goal is to move the water with maximum force and minimum noise, making the submarine a ghost in the ocean.

Shaft Lines and Bearings: Transmitting the Power

The mechanical power from the turbines and gearboxes is transmitted to the propellers via shaft lines. These are robust shafts that pass through watertight seals in the submarine’s hull. The bearings that support these shaft lines are critical for smooth, efficient power transfer and must withstand immense forces and rotational speeds.

Hydrodynamic Efficiency and Noise Reduction: The Pillars of Stealth

The entire propulsion train, from the reactor to the propeller, is designed with a relentless focus on hydrodynamic efficiency and noise reduction. Any vibration or noise generated by the propulsion system can betray the submarine’s presence to enemy sonar. Therefore, extensive efforts are made to isolate vibrating components, dampen noise, and streamline the flow of water around the hull. This pursuit of silence is akin to a composer striving for perfect harmony, where every element contributes to an overall quiet masterpiece.

Recent discussions surrounding the advancements in nuclear submarine propulsion have sparked interest in the strategic implications of these technologies. For those looking to delve deeper into the topic, an insightful article can be found that explores the intricacies of nuclear propulsion systems and their impact on naval warfare. You can read more about it in this detailed analysis, which sheds light on the secrets behind these powerful vessels and their role in modern military strategies.

Auxiliary Propulsion Systems: The Backup and the Silent Runner

| Metric | Description | Typical Value / Range | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reactor Type | Type of nuclear reactor used for propulsion | Pressurized Water Reactor (PWR) | Most common for naval submarines due to safety and compactness |

| Thermal Power Output | Heat generated by the reactor core | 150-200 MWt | Varies by submarine class and reactor design |

| Propulsion Power | Mechanical power delivered to the propeller shaft | 30,000-60,000 shp (shaft horsepower) | Enables high underwater speeds |

| Operational Endurance | Duration submarine can operate without refueling | 20-30 years | Depends on reactor fuel and maintenance |

| Coolant Type | Fluid used to transfer heat from reactor core | Light Water | Acts as both coolant and neutron moderator |

| Noise Reduction Techniques | Methods to minimize acoustic signature | Pump-jet propulsors, sound-isolating mounts | Critical for stealth operations |

| Speed (Submerged) | Maximum underwater speed | 25-35 knots | Depends on hull design and propulsion efficiency |

| Reactor Fuel Type | Material used as nuclear fuel | Highly Enriched Uranium (HEU) | Enables compact core and long life |

While the nuclear reactor is the primary engine, submarines are equipped with auxiliary propulsion systems for critical backup and for periods of utmost stealth. These systems, while less powerful, are indispensable for operational flexibility.

Electric Motors and Batteries: The Silent Dancers

For silent running and low-speed maneuvering, submarines rely on electric motors powered by their extensive battery banks. These electric motors are connected to the propeller shafts, allowing the vessel to move with an almost imperceptible hum. This capability is crucial for clandestine operations, allowing the submarine to loiter undetected on sonar screens. The interplay between charging the batteries via the main propulsion and using them for silent running is a carefully orchestrated maneuver.

Diesel-Electric Systems (Historical and Backup): A Glimpse into the Past

In earlier generations of submarines, and still as a backup in some nuclear vessels, diesel-electric systems played a significant role. Diesel engines, when operating on the surface or at periscope depth, could generate electricity to charge batteries and provide direct propulsion. However, these systems are noisy and require the submarine to be near the surface for air intake, compromising stealth. While largely superseded by the continuous power of nuclear propulsion, their legacy highlights the evolution of underwater warfare.

Air-Independent Propulsion (AIP) Systems: The Next Step in Endurance

The most recent advancements in submarine propulsion have seen the development and implementation of Air-Independent Propulsion (AIP) systems. These technologies, while not nuclear, allow non-nuclear submarines to operate submerged for significantly longer periods than traditional diesel-electric vessels. Various AIP technologies exist, including fuel cells and Stirling engines, all aiming to provide power without the need for atmospheric oxygen. While not an untold secret in the public domain, their integration and specific operational profiles on non-nuclear submarines represent a significant leap forward in their capabilities.

FAQs

What type of reactor is commonly used in nuclear submarine propulsion?

Nuclear submarines typically use pressurized water reactors (PWRs) for propulsion. These reactors use enriched uranium as fuel and water as both a coolant and a neutron moderator.

How does nuclear propulsion benefit submarines compared to conventional propulsion?

Nuclear propulsion allows submarines to operate underwater for extended periods without surfacing, providing greater endurance, higher speeds, and reduced need for refueling compared to diesel-electric submarines.

What safety measures are in place to prevent nuclear accidents on submarines?

Nuclear submarines are equipped with multiple redundant safety systems, including automatic shutdown mechanisms, containment structures, and rigorous crew training to handle emergencies and prevent radiation leaks.

How is the heat generated by the nuclear reactor converted into propulsion?

The reactor heats water to produce steam, which drives turbines connected to the submarine’s propeller shaft, generating thrust. The steam is then condensed back into water and recirculated in a closed loop.

Are the details of nuclear submarine propulsion publicly available?

While general principles of nuclear submarine propulsion are publicly known, specific technical details and operational secrets are classified by governments to maintain national security and protect sensitive technology.