The depths of the world’s oceans, vast and largely uncharted, present a unique set of challenges and opportunities for surveillance. As human activity, from commercial shipping and resource extraction to national security interests, increasingly penetrates these sub-surface realms, the need for robust underwater surveillance networks has become paramount. These intricate systems act as the eyes and ears of humanity beneath the waves, constantly monitoring, analyzing, and reporting on the dynamic environment. This article will delve into the multifaceted world of underwater surveillance networks, exploring their technological underpinnings, operational applications, and the ongoing evolution that promises to enhance our understanding and stewardship of this critical domain.

The oceans represent a frontier of immense strategic and economic importance. They are highways for global trade, reservoirs of vital resources, and crucial battlegrounds in an increasingly complex geopolitical landscape. Understanding what transpires beneath the surface is no longer a luxury but a necessity. Without effective surveillance, nations risk compromised maritime security, unchecked environmental degradation, and missed opportunities for scientific discovery.

Maritime Domain Awareness

Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA) is the effective understanding of all activities within a specific maritime area that could impact the security, safety, economy, or environment. Underwater surveillance networks are a cornerstone of comprehensive MDA, extending situational awareness far beyond the reach of surface-based sensors. The ability to detect and track submarines, mines, or unauthorized sub-surface constructs is critical for national defense and the protection of maritime trade routes. This vigilance acts as a deterrent, signaling a clear intent to monitor and respond to any potential threats.

Resource Protection and Management

The ocean floor is increasingly becoming a source of valuable resources, from hydrocarbons in deep-sea oil and gas fields to rare earth minerals. Effective surveillance is essential for monitoring exploration and extraction activities, ensuring compliance with environmental regulations, and preventing illegal or unauthorized exploitation. Furthermore, the health of marine ecosystems, vital for global food security and biodiversity, requires continuous monitoring of factors such as pollution levels, changes in marine life populations, and the impact of human activities on sensitive habitats.

Environmental Monitoring and Research

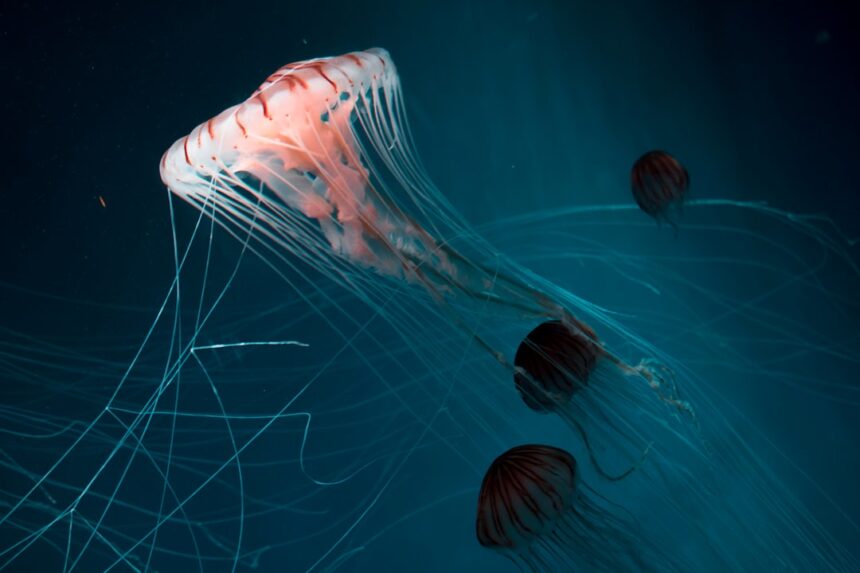

Beyond human activities, the oceans are a dynamic and complex environment that warrants constant scientific observation. Underwater surveillance networks provide invaluable data for understanding climate change impacts, oceanic currents, seismic activity, and the behavior of marine life. These networks act as distributed laboratories, collecting information that can advance our understanding of the planet’s most extensive ecosystem and inform crucial environmental policies.

Underwater surveillance networks are becoming increasingly important for various applications, including environmental monitoring, security, and military operations. A related article that delves into the advancements and challenges of these technologies can be found at In the War Room. This resource provides insights into the latest developments in underwater surveillance systems and their implications for future operations.

Technological Pillars of Underwater Surveillance

The development of effective underwater surveillance networks is a testament to human ingenuity in overcoming the immense challenges posed by the marine environment. Water, with its density, salinity, and currents, significantly impedes the propagation of signals, demanding specialized technologies for effective detection and communication. These technologies form the interconnected web that allows us to “see” in the deep.

Acoustic Sensing: The Dominant Voice

Given the limitations of electromagnetic waves in water, acoustic sensing remains the most prevalent and effective method for underwater detection and surveillance. Sound travels further and more efficiently in water than light or radio waves, making it the primary medium for underwater communication and sensing.

Sonar Systems: Active and Passive

- Active Sonar: This technology emits sound pulses and listens for their echoes bouncing off objects. The time it takes for the echo to return, along with its characteristics, provides information about the object’s range, size, and even material composition. Active sonar is like a powerful shout into the darkness, listening for the reverberations. However, its use can betray the presence of the sonar platform itself, leading to potential countermeasures. Sonar arrays, with their multiple transducers, can provide directional information and create detailed acoustic maps. These can range from simple hull-mounted systems to complex towed arrays or seabed-mounted facilities.

- Passive Sonar: This method simply listens for sounds generated by targets. Submarines, for instance, produce characteristic acoustic signatures from their machinery and propellers. By analyzing these sounds, skilled operators can identify the type of vessel, its direction, and even its approximate speed. Passive sonar is the ultimate eavesdropper, gathering intelligence without revealing its own presence. This is crucial for covert operations and long-term monitoring of areas where active interrogation might be undesirable. The development of advanced signal processing algorithms is vital for distinguishing target sounds from the pervasive “noise” of the ocean, which includes marine life, shipping traffic, and weather phenomena.

Hydrophone Networks: The Listening Grid

Arrays of hydrophones, strategically deployed on the seabed or moored in the water column, form passive listening networks. These networks can cover vast areas, providing continuous monitoring of acoustic activity. When linked together, they can triangulate the location of sound sources with remarkable accuracy. These networks are the silent sentinels of the ocean depths, constantly absorbing the whispers and roars of the submerged world. A global network of hydrophones, for instance, can provide early warning of seismic events or track the movement of large marine animals.

Optical and Electromagnetic Sensing: Reaching the Shallower Waters

While acoustic methods dominate deep-water surveillance, optical and electromagnetic sensors play crucial roles in shallower regions and for specific applications. These technologies offer different perspectives and can complement acoustic data.

Remote Sensing: Eyes from Above

Satellites equipped with specialized sensors can observe the ocean surface, detecting phenomena like oil slicks, algal blooms, and ship wakes. Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) satellites, for example, can penetrate cloud cover and even detect sub-surface objects that influence surface currents or create tell-tale disturbances. This provides a broad overview and can direct more detailed investigations. Remote sensing acts as the scout, providing initial intelligence from a high vantage point.

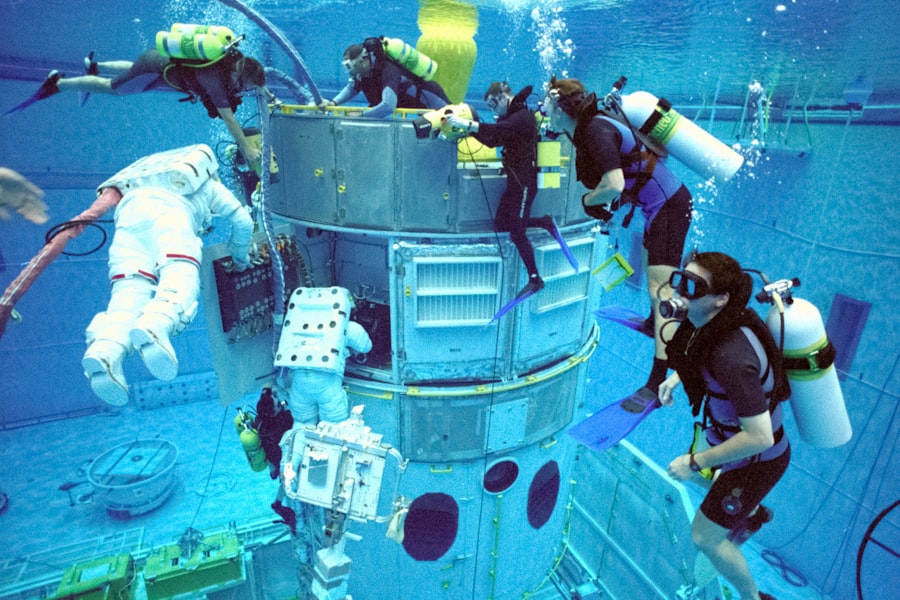

Cameras and Imaging Systems: Visual Confirmation

In shallower waters, divers, remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), and unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs) can deploy cameras for visual inspection and data collection. High-resolution, low-light cameras are essential for capturing clear images in the often-dim underwater environment. These systems are critical for detailed inspections of infrastructure, marine life surveys, and forensic investigations. Visual confirmation solidifies the information gathered by other sensors.

Other Sensing Modalities

Beyond acoustics and optics, several other sensing technologies contribute to underwater surveillance, offering unique capabilities:

Magnetic Anomaly Detectors (MAD)

MAD systems detect variations in the Earth’s magnetic field caused by the presence of ferromagnetic objects, such as submarines or unexploded ordnance. These sensors are often mounted on aircraft or surface vessels and are particularly effective for detecting submerged metallic objects. The MAD system is like a compass sensitive to anomalies, pointing the way to hidden ferrous presences.

Chemical and Biological Sensors

These sensors can detect changes in water chemistry caused by pollution, the presence of specific organisms, or even biological warfare agents. They are vital for environmental monitoring and early warning systems. The ability to taste the water, in a scientific sense, provides crucial insights into its health and potential contaminants.

Radar and LIDAR

While their range is limited underwater, radar and LIDAR can be used in shallow waters or for specific applications like detecting surface targets that cast shadows or alter the water’s reflectivity. LIDAR, in particular, can provide highly detailed topographical maps of the seabed in clear water.

Deploying the Sentinels: Network Architectures and Platforms

The effectiveness of underwater surveillance hinges not only on the individual sensors but also on how they are integrated into robust and resilient networks. The architectural design and the platforms utilized for deployment are crucial for achieving broad coverage, timely data relay, and operational flexibility.

Fixed Seabed Networks: The Unwavering Watch

Deploying sensor arrays and communication nodes directly onto the ocean floor creates fixed networks. These systems offer long-term, persistent monitoring capabilities for strategically important areas. They act as the permanent guardians of key maritime regions.

Undersea Fiber Optic Cables

These advanced networks leverage the vast infrastructure of undersea communication cables, integrating sensor data directly into these high-bandwidth conduits. This allows for real-time data transmission from remote seabed sensors to shore-based analysis centers. The transformation of communication highways into intelligence arteries is a significant leap in network capability.

Ocean Bottom Seismometers (OBS) and Hydrophone Arrays

Permanent installations of OBS and hydrophone arrays form the backbone of many fixed acoustic surveillance networks. These can detect seismic activity, monitor submarine traffic, and even track large cetaceans. Their fixed nature ensures consistent data collection over extended periods.

Mobile and Semi-Mobile Platforms: The Dynamic Patrol

To adapt to changing threats and cover wider areas, mobile and semi-mobile platforms are essential. These systems provide flexibility and can be deployed rapidly to investigate anomalies or respond to emerging situations. They are the patrolling guardians, moving where needed.

Unmanned Underwater Vehicles (UUVs) and Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs)

These robotic vehicles are revolutionizing underwater surveillance. UUVs, often tethered to a support vessel, can perform detailed inspections and data collection. AUVs, on the other hand, are autonomous and can navigate pre-programmed routes or adapt their mission based on sensor input. They are becoming the scouts and surveyors of the deep, capable of long-duration missions and operating in hazardous environments.

Surface Vessels and Submarines

Traditional platforms like surface warships and submarines remain vital components of underwater surveillance. They can carry a wide array of sensors, conduct active sonar sweeps, and deploy UUVs/AUVs. They represent the command and control elements, orchestrating the broader surveillance effort. A submarine not only acts as a platform but can also be a target and a sensor simultaneously.

Buoy Systems and Drifters: The Mobile Data Gatherers

Moored buoys and drifting sensors with integrated acoustic and environmental sensors provide distributed monitoring capabilities. They can transmit data wirelessly to satellites or passing vessels, acting as mobile nodes within a larger network. These are the roving informants, collecting tidbits of information from across the ocean.

Acoustic Monitoring Buoys

These buoys are equipped with hydrophones and can transmit acoustic data in real-time, providing continuous monitoring of specific areas. They are particularly useful for tracking the movement of marine mammals or monitoring shipping lanes.

Environmental Drifters

Designed to passively drift with ocean currents, these buoys carry a suite of sensors to measure water temperature, salinity, currents, and other environmental parameters. They contribute to a holistic understanding of oceanic conditions, essential for both scientific research and operational planning.

Data Management and Analysis: Making Sense of the Submerged World

The sheer volume of data generated by underwater surveillance networks presents a significant challenge. Effective analysis and interpretation are crucial for transforming raw sensor readings into actionable intelligence. This is where the true power of these networks is unleashed.

Real-Time Data Processing and Fusion

Sophisticated algorithms and powerful computing platforms are required to process massive streams of acoustic, optical, and other sensor data in real-time. Data fusion techniques integrate information from multiple sensors to provide a more comprehensive and accurate picture of the underwater environment. This is like stitching together fragments of a puzzle to reveal the complete image.

Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence (AI)

The application of AI and machine learning is revolutionizing acoustic signal processing. ML algorithms can be trained to recognize specific acoustic signatures of submarines, marine life, and other underwater phenomena with increasing accuracy. This automation reduces the burden on human analysts and allows for faster threat detection. AI acts as the super-analyzer, sifting through mountains of data at lightning speed.

Pattern Recognition and Anomaly Detection

Sophisticated software can identify unusual patterns in sensor data that may indicate illicit activities or unexpected environmental changes. This proactive approach allows for early detection of potential threats before they escalate. The ability to spot the outlier in a sea of normalcy is a critical skill.

Historical Data Archiving and Long-Term Trend Analysis

Accumulating historical data allows for the identification of long-term trends in oceanographic conditions, maritime traffic, and acoustic environments. This temporal perspective is vital for understanding climate change impacts, predicting future behavior, and building comprehensive threat assessments. Historical records are the ocean’s memory, providing context and foresight.

Threat Assessment and Intelligence Reporting

The ultimate goal of underwater surveillance is to provide timely and accurate intelligence for decision-making. This involves identifying threats, assessing their significance, and reporting findings to relevant authorities. The information gathered must be relevant, concise, and actionable. From unseen depths to informed action, this is the final conduit.

Underwater surveillance networks have become increasingly important for national security and environmental monitoring. These systems utilize advanced technology to gather data on marine life, monitor underwater activities, and detect potential threats. For a deeper understanding of the implications and advancements in this field, you can explore a related article that discusses the latest innovations and challenges in underwater surveillance. This insightful piece can be found here.

Challenges and the Future of Underwater Surveillance

| Metric | Description | Typical Range/Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Range | Maximum distance at which an object can be detected by the network | 500 – 5000 | meters |

| Sensor Type | Type of sensors used in the network | Hydrophones, Sonar, Acoustic Modems | N/A |

| Network Coverage Area | Total area monitored by the underwater surveillance network | 1 – 100 | square kilometers |

| Data Transmission Rate | Speed of data transfer between underwater nodes and surface stations | 10 – 1000 | kbps |

| Power Consumption | Average power usage of underwater sensor nodes | 1 – 10 | Watts |

| Battery Life | Operational time before battery replacement or recharge | 6 – 24 | months |

| Latency | Time delay in data transmission across the network | 100 – 500 | milliseconds |

| Node Density | Number of sensor nodes per square kilometer | 5 – 50 | nodes/km² |

| Operating Depth | Depth range at which the sensors can operate effectively | 10 – 1000 | meters |

| False Alarm Rate | Percentage of false detections reported by the system | 1 – 5 | % |

Despite significant advancements, underwater surveillance networks face ongoing challenges. The vastness of the oceans, the harsh environmental conditions, and the ever-evolving nature of threats necessitate continuous innovation and adaptation.

Environmental Challenges

The ocean’s dynamic nature itself poses a formidable challenge. Corrosive saltwater, high pressures at depth, changing ocean temperatures, and unpredictable currents can degrade sensor performance and damage equipment. Maintenance and repair of submerged infrastructure are also complex and costly endeavors. The ocean is a relentless adversary in its sheer physicality.

Technological Limitations and Future Frontiers

While acoustic sensing is effective, it has limitations. Stealth technologies employed by modern submarines can make them harder to detect. The development of non-acoustic sensing methods and more advanced signal processing continues to be an area of active research. The quest for the perfect underwater “radar” continues.

Quantum Sensing

Emerging research in quantum sensing holds the promise of revolutionizing underwater detection. Techniques like quantum radar could offer unparalleled sensitivity and range, potentially overcoming many of the limitations of current acoustic and electromagnetic sensors. This represents a leap into an entirely new paradigm of detection.

Swarm Robotics and Distributed Sensing

The concept of deploying swarms of interconnected UUVs and AUVs is gaining traction. These swarms could cooperate to map vast areas, track targets, and gather distributed data more efficiently than individual platforms. A coordinated ballet of autonomous agents in the deep.

Interoperability and Data Sharing

Ensuring interoperability between different nations’ surveillance systems and facilitating secure data sharing are critical for global maritime security. Collaborative efforts are essential to build comprehensive and effective underwater surveillance capabilities. A united front beneath the waves.

Ethical and Legal Considerations

As underwater surveillance becomes more pervasive, ethical and legal considerations surrounding data privacy, the use of autonomous systems, and potential impacts on marine life will become increasingly important. Responsible development and deployment are paramount. The ethical compass must guide our technological advancement.

In conclusion, underwater surveillance networks are indispensable tools for understanding and protecting our oceans. From the deep trenches to the continental shelves, these intricate systems act as our vigilant sentinels, providing critical intelligence for national security, economic prosperity, and environmental stewardship. The ongoing evolution of sensor technologies, network architectures, and data analysis techniques promises to further enhance our ability to monitor and interact with the submerged world, ensuring its health and security for generations to come. The future of underwater surveillance lies in increasingly sophisticated integration, artificial intelligence, and a commitment to responsible innovation, transforming our view of the final frontier.

FAQs

What are underwater surveillance networks?

Underwater surveillance networks are systems composed of sensors, communication devices, and monitoring equipment deployed underwater to detect, track, and monitor activities or objects beneath the water surface.

What are the primary applications of underwater surveillance networks?

These networks are used for maritime security, environmental monitoring, underwater navigation, military defense, and scientific research, including tracking marine life and detecting underwater threats.

How do underwater surveillance networks communicate data?

They typically use acoustic signals for underwater communication, as radio waves do not travel well underwater. Some systems also use optical or electromagnetic methods for short-range communication.

What types of sensors are used in underwater surveillance networks?

Common sensors include hydrophones for detecting sound, sonar systems for mapping and object detection, pressure sensors, temperature sensors, and chemical sensors to monitor water quality.

What challenges are associated with underwater surveillance networks?

Challenges include limited communication bandwidth, power supply constraints, harsh underwater environmental conditions, signal attenuation, and the difficulty of maintaining and deploying equipment underwater.